Benton Harbor, Michigan: A Small City with Big Problems

By: Scott R. Burgess

Opened in 1934 when George Purdy Wilder purchased the former Cookson’s Drug Store at 696 E. Main Street, Wilder’s Drug Store was a fixture in Benton Harbor, Michigan. It was such a landmark in the community that real estate advertisements sometimes gave no address, just a note that a property was “near Wilder’s Drug Store.”[1] Expanding on the store’s success, the family moved to a new, larger store just across the street in 1948. When “Dad” Wilder (as he was known) retired around 1954, his son and daughter-in-law, Ray and Edna Wilder, took over the business.[2] Wilder’s Drug Store continued to serve the community until 1971. Wilder’s Books, located down the street at 143 E. Main Street, opened in 1967 to capitalize on the popularity of the book section that Ray and Edna had added to the drug store.

When the Wilders announced that Wilder’s Drug Store would be closing on April 3, 1971, it made front-page news. The bookstore closed on April 1 of the following year after having opened a companion location across the river in St. Joseph. Wilder’s stores were two of at least sixty-nine Benton Harbor businesses that closed between 1965 and 1975, while in St. Joseph there was only a handful of closings.[3] The Wilders, longtime area residents, also joined the overwhelming number of white families who moved away during this decade. In this paper, I will use Wilder’s Drug Store and the recollections of its proprietors as a frame to help understand what happened in Benton Harbor during this decade.

Urban decline is a nearly universal problem, affecting cities of all sizes.[4] The city of Benton Harbor (1960 Census population of 19,136) was hit particularly hard in the 1960s and 1970s by the loss of industrial jobs, rising crime, the disruption of urban renewal programs, and the subsequent scourge of white flight. And the contrast with the city of St. Joseph (1960 Census: 11,755), which lies just across the river and down the Lake Michigan shoreline, is especially stark.[5] In this paper I will show that a series of violent incidents, the departure of most of the city’s White population and the resultant segregation, and the failure of several attempts to address the root causes of these problems all have combined to create an atmosphere of racial division, abandonment, and distrust that persists to this day.

Historiography

There is no shortage of formal and informal analysis regarding the decline of Benton Harbor. Indeed, almost anyone who lives in southwest Michigan has an opinion about what went wrong in the city. Many newspapers, magazines, and journals have published pieces about the area, a remarkable amount of coverage for a city of such small size.[6] Numerous sources cover the early history of Benton Harbor, St. Joseph, and the surrounding area. Orville Coolidge’s extensive A Twentieth Century History of Berrien County Michigan was published in 1906. It follows the format of many such books of the time, with the first section discussing the history of the area and the remainder devoted to biographical sketches of notable locals, nearly all of whom are white males.[7]

Several publications have been devoted to current events in Benton Harbor. The events recounted in journalist Alex Kotlowitz’s book The Other Side of the River happen in Benton Harbor and St. Joseph in the early 1990s, but the author places them in the context of the decline covered in this paper. He discusses “the myths of old,” his term for the perceptions of the population of both cities regarding the impoverishment of Benton Harbor and the growth of St. Joseph.[8] The oral histories that Kotlowitz gathered constitute an important record of the attitudes of city residents, and his follow-up article in 2021 details how little these attitudes have changed over the decades. In her dissertation Race, Power, and Economic Extraction in Benton Harbor, MI, Sociologist Louise Seamster finds Kotlowitz’s focus on the racial divide in Benton Harbor/St. Joseph to be too narrow. She writes that while Kotlowitz saw the cities divided by the river, she saw “divisions bisecting the community in multiple directions.”[9] Seamster describes Benton Harbor as a “walled city,” metaphorically walled off from the outside or divided by walls within its own community. She focuses on two attempts at reviving the city and argues that they actually siphoned off resources from the Black community to benefit a white urban regime.[10]

In her thesis Exit 33: The Economic Decline of Benton Harbor, Michigan, Benton Harbor teacher Shay Briggs examines the period from the 1950s to the 1990s. She cites “job loss, segregation, urban renewal and racial tension” as the causes of this decline.[11] She concludes, however, that “it’s not that one thing went wrong, but that many vast changes happened in a very short period of time.”[12] A short but in-depth discussion of the decline of Benton Harbor forms the preface to Robert C. Myers’ photo essay Greetings from Benton Harbor. Myers recounts the early history of the city and surrounding area and then asks, simply, “What Happened to Benton Harbor?”[13] He adds to the work of other historians, arguing that unethical real-estate practices and the development of the Interstate Highway System also played a role in the city’s decline. Throughout the book Myers engages the difficult questions of systemic failure and economic injustice, including the stories of individuals, corporations, and local governments. Overall, his assessment coincides with Briggs: no one factor, or even a small number of factors, can explain the entire situation.

Widening the focus outside of Southwest Michigan, much has been written about the roots of urban decay that is applicable to the situation of Benton Harbor. Thomas Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis argues that urban inequality stems primarily from policy choices by corporations, governmental officials, and other powerful forces. Sugrue focuses on Detroit, but many of his lessons apply to Benton Harbor and other cities as well. In his preface he states that “decades of public policy, corporate decision making, and racial hostility have shaped today’s city and have constrained its future.”[14] Detroit’s troubles are often perceived to have begun with the riots of 1967, but Sugrue demonstrates that “the forces of economic decay and racial animosity” were already well-entrenched by that point.[15] My research shows the same to be true for Benton Harbor prior to its pivotal riots in 1966.

In his study of public policy and the underclass, The Truly Disadvantaged, William Julius Wilson takes these arguments a step further. He argues that while contemporary policies and decisions systemically disadvantage the underclass, it is even more important to look at historical policies which created this system. Wilson writes that “a full appreciation of the effects of historic discrimination is impossible without taking into account other historical and contemporary forces that have also shaped the experiences and behaviors of impoverished urban minorities.”[16] Nicholas Lemann’s The Promised Land sees the broken promises of the Second Great Migration written in the cracked sidewalks of Chicago. Like Sugrue, Lemann argues that government policy and political machinations encouraged Black citizens from the South to move to the urban North and then abandoned them to circumstances that were in many ways worse than the situations they left. However, Lemann delves deeper into potential solutions and sounds a more hopeful note than the other authors considered here.[17]

In their book American Apartheid, Douglas Massey and Mary Denton argue that racial segregation is a principal cause of urban decline rather than an effect. They specifically contradict Wilson, arguing that “in the absence of segregation, these structural changes would not have produced the disastrous economic and social outcomes observed in inner cities.”[18] All of these sources acknowledge the complex challenges of urban development in the second half of the twentieth century. Most significantly, they all agree that while racism is part of the problem, it is not the entire problem.

Methodology

The main primary source for this research is newspaper accounts. The most prominent area newspapers, the Herald-Press (St. Joseph) and the News-Palladium (Benton Harbor), were published under the same corporate structure and merged under the Herald-Palladium masthead in 1975.[19] Prior to the merger, the two papers often ran identical pages under their respective mastheads.[20] If Benton Harbor was mentioned in the national press, it was usually with reference to one of three things: corporate news (often regarding Whirlpool), sports news, or urban strife and decay. My sources include articles from the New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and other national papers. Due to Benton Harbor’s proximity to Chicago, that much-larger city’s papers covered Berrien County affairs somewhat regularly. In addition to crime and sports articles, the Chicago press was also interested in festivals and other happenings of interest to their readers who vacationed in Berrien County. Taken together with the personal recollections, these newspaper accounts provide the material for a cultural analysis of the attitudes and perceptions that informed the decisions of area residents and policy makers.

Along with the newspaper accounts, I will make use of the personal accounts of Ray and Edna Wilder. My family history collection includes several narratives from the Wilders, as well as a scrapbook of newspaper clippings and other ephemera that tell their part of the Benton Harbor story. As the owners of Wilder’s Drug Store and major figures in city and township politics, Ray and Edna offer a helpful lens through which to view this research. Numerous other narrative histories of this area covering various time periods have been published by local residents and can serve as primary sources.[21] One of these, Kathryn Zerler’s On the Banks of the Ole St. Joe, is notable due to the author’s choice of focus. The subtitle describes it as “A Selected History of the Twin Cities Area of St. Joseph and Benton Harbor, Michigan.” However, of its ten chapters, only two even mention Benton Harbor, and its “downtown walking tour” only covers seven blocks, all of which are on the St. Joseph side of the river.[22]

R.L. Polk and Company has published City Directories for the combined Benton Harbor / St. Joseph area since 1902. For the bracket years of 1965 and 1975, I used these directories to identify businesses that ceased operation during that time, which in turn guided my research in the newspaper archive. The street listings allowed me to target the main commercial street in each city to focus this research. When considered side-by-side, these two directories paint a stark picture of the differences between Benton Harbor and St. Joseph and the degree of change during the subject decade.

Another primary data source is U.S. Census records for the years 1960 and 1980, which bracket my subject decade. A significant challenge in studying census data for this area is its small population. Though it was the largest city in Berrien County in 1960, the population of Benton Harbor was only 19,136, not nearly large enough to anchor a Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined at that time.[23] Therefore, even though Berrien County was considered an SMSA in 1980, it is still challenging to compare the two censuses directly due to this lack of aggregated data. Basic comparable information is available, however, and allows me to contrast Benton Harbor, St. Joseph, and surrounding townships in matters of population, racial and income demographics, and some of the changes over these two consequential decades.[24]

It is necessary to include a note on terminology. With fewer than twenty thousand residents at its population peak, why is Benton Harbor properly referred to as a city? Under Michigan law, a city is defined by its legal status rather than its size.[25] Cities in Michigan have, by their charter, withdrawn from the surrounding township(s) and are thus required to collect their own taxes, provide their own services, and essentially operate as an independent entity.[26] For Benton Harbor, this is more than a legal or academic question. While the independence granted by being a Michigan city may have been desirable in the early 1900s, it allowed the surrounding townships to keep themselves and their residents insulated from the economic collapse that began in the mid-twentieth century. There were several attempts over the years to annex adjacent areas to the city, but these rarely succeeded and Benton Harbor was left to its own devices as its troubles mounted.[27]

Why is it important to study the decline of this struggling small city far from the centers of power? The manner in which the problems have played out brought researcher Joshua Ewalt to describe Benton Harbor as “a small town with global significance.”[28] He went on to say that it “offers a very strong opportunity to explore questions of place [and] power geometries.”[29] Combining cultural and structural analysis will help to fill in the story of the city, and perhaps by increasing the understanding of what happened, this research will encourage and inform those who are working hard today to lift Benton Harbor from the ashes.

A Prosperous Beginning

Benton Harbor had a prosperous beginning. Organized as a village in 1836 and incorporated as a city in 1891, it was described by Judge Orville W. Coolidge in 1906 as “the wealthiest and most populous city in the county.”[30] Even early on, though, distinctions between Benton Harbor and neighboring St. Joseph were readily made. An 1869 visitor noted that while St. Joseph had ambitions to rival Chicago, neighboring Benton Harbor “is younger in its growth…and has no lofty, pretentious residences to please the eye.”[31] Historian Robert Myers wrote that in post-war Benton Harbor “big industries hummed with productivity… The city was home to the world’s largest outdoor fruit market… Retail stores, theaters, and hotels in the downtown catered to visitors and locals alike who jammed the busy sidewalks.”[32] In the 1960s, though, the industries began to close their area factories, the fruit market moved out of downtown, and smaller businesses began to close.

Urban Renewal?

Benton Harbor became a candidate for urban renewal in the 1960s, and the process set the stage for the divisions to come. “B.H. URBAN RENEWAL WINS!” proclaimed the jubilant headline of the Benton Harbor News-Palladium on April 7, 1964. The overwhelming voter approval showed how eager many residents were to see the city revitalized.[33] In May of 1966 the city of Benton Harbor began acquiring properties for its urban renewal projects, and on January 9, 1967, the city commission filed its first round of condemnation lawsuits. According to the city’s Urban Renewal Director Leslie Cripps, the suits were necessary “because of inability to negotiate with the property owners.”[34] Overall, the plan called for the demolition of 281 buildings and clearing of 121 acres. A 1989 report from the U.S. Department of Commerce observed that “urban renewal demolished the black ghetto on the flats west of the downtown business district, forcing the residents to find homes in other parts of the city.”[35] The costs and benefits of urban renewal were unevenly distributed.

Apart from the renewal program, numerous plans to draw more traffic, and therefore more business, to Benton Harbor were made, re-made, and eventually abandoned. A freeway interchange was constructed at the intersection of Lakeshore Drive and Klock Road on the west side of Benton Harbor and is clearly visible in a 1966 aerial photograph of the city.[36] As the nearby interstate highways were under construction, there were several proposals to extend one or another of these to meet this interchange.[37] These often had a negative effect on property values, since owners found it difficult to sell a property that was potentially slated to be paved over. None of these plans ever came to fruition, though, and eventually the interchange was demolished by the Michigan Department of Transportation. Today the intersection of Lakeshore and Klock is equipped with a standard stoplight, and I-94 and I-196 take motorists right past the eastern edge of the city.

The Decline of Benton Harbor

Accounts of the decline of Benton Harbor often point to August 1966 as a pivotal time. On Sunday night, August 28,th a few incidents of vandalism and petty theft earlier in the week grew into a city-wide disturbance.[38] An official of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission set a meeting for Tuesday evening in hopes of diffusing tensions. At this meeting, city officials urged calm: “Benton Harbor Mayor Wilbert Smith and Benton Township Supervisor Ray Wilder urged residents to stay in their homes after dark, keep track of their children, and act in good faith to end the disorder.”[39] But it was not to be. That night 16-year-old Cecil Hunt was killed in a drive-by shooting, and Michigan Governor George Romney dispatched the state police in an attempt to restore order.[40] A suspect in the shooting was arrested the following day but then released, and the murder case has never officially been solved.[41] Thursday’s newspapers stated that police and “Peace Squads” had restored calm to the city, but they were not able to restore the trust of the citizens.[42]

The 1966 riots were followed by a general increase in crime in Benton Harbor. One incident the following year had a major impact on the town and on the Wilder family. Late in the evening of October 20, 1967, 83-year-old widow Millie Peapples was murdered in her home at 165 Benton Street, directly behind Wilder’s Drug Store.[43] Her house had been broken into and ransacked. Days later, four boys, all under eighteen years of age, were arrested for the crime[44]. Alongside the newspaper coverage of the murder and subsequent investigation, Ray Wilder, owner of Wilder’s Drug Store and then Benton Township Supervisor, issued a statement vowing cooperation with the city in fighting “the soaring crime rate in our community.”[45] The murder of Millie Peapples was one of three crimes described on that front page, and in a small offset box with the headline “Shock you? ..It Did Us, Too!”, the Herald-Palladium published the following editor’s note:

“If the local crime news on this front page shocks readers, so did the nature and extent of crime in and around Benton Harbor shock this newspaper’s editorial staff last night. Perhaps shock treatment is what is needed to make the public realize that the combined local and county law enforcement apparatus is not adequate to meet today’s community problems. Aroused, the public just might convey the idea to appropriate public officials.”[46]

The city’s residents and officials were clearly rattled, and those who could afford to leave began eyeing the exits.

Nonetheless, there were many in town who were not ready to give up. At a public forum on May 14, 1970, Benton Harbor Police Chief William McClaran told a gathering of about sixty business owners and citizens that “a lot of the problem of lawlessness in downtown Benton Harbor is more imagined than real.”[47] The gathering was hosted by downtown property owner Rex Sheeley, in hopes of allaying the concerns of fellow merchants. Various participants offered their thoughts as to what the problem really was, but nearly all expressed confidence that the downtown was essentially a safe place to conduct business as usual. The one merchant who was quoted as remaining skeptical was the only woman mentioned in the newspaper account. Edna Wilder complained of “having to step over whiskey bottles and walk around bums while going to work. ‘What does a lady from St. Joe think of that?’” Her quote was accompanied by a photo with the somewhat dismissive caption of “Mrs. Edna Wilder: Steps Over Whiskey Jugs.”[48] Despite this public attempt at optimism, the departure of business from Benton Harbor continued unabated.

Benton Harbor / St. Joseph city directories provide some stark details on the disproportionate effects of this exodus. Most Benton Harbor businesses are located on Main Street, which stretches about twenty blocks from the river to the city’s eastern boundary. Examining the business listings on Main Street yields some stark numbers. In 1965, 151 businesses were listed along this busy thoroughfare. These included all of the services a city might need, such as grocers, gasoline stations, department stores, and pharmacies (including Wilder’s Drug Store). By 1975, Wilder’s and 68 other businesses had left this street, and while a few of the buildings had been filled with churches or offices, most were listed in the 1975 directory as “vacant” or had been demolished altogether. Looking across the river to St. Joseph, its main business thoroughfare, State Street, had lost just three businesses in that same period of time.[49] The combined Benton Harbor/St. Joseph business directory had actually increased from 54 pages of listings in 1965 to 63 in 1975. Businesses were clearly still thriving, but only on the south side of the St. Joseph River.

One of the first to depart Benton Harbor was the Troost Brothers furniture store at the corner of Main and Pipestone. A full-page advertisement in the August 19, 1965 edition of the News-Palladium declares that “A Great Store Says ‘Good-Bye’ to Benton Harbor.”[50] The store, which was one of several owned by the Troost family, had been open since 1926. In 1969, David Pollyea, whose family had been in business in Benton Harbor since 1898, closed his clothing store at 102 Main Street after twenty-two years at that location. Pollyea stated that “business had been down somewhat in recent years” but that “he doesn’t anticipate any other stores closing downtown because ‘there’s still a demand for their services and things will improve.’”[51] The News-Palladium of Saturday, April 28, 1973 reported that “on Sunday at 7 p.m. a Chinese dynasty will come to an end in Benton Harbor.”[52] The Hung Fong restaurant, 165 East Main Street, was closing after 54 years in business. Owner Arkie Chin, 74, said that it was not possible to make needed updates and repairs to his building because of declining business. Chin had also recently been hospitalized after being beaten during a robbery.

In 1974, the News-Palladium ran the headline of “Familiar Story – BH Firm Closing.”[53] O.K. Electric, located two blocks south of Main on Pipestone Street, was closing after 39 years. Owner Howard E. ‘Doc’ Bartels, 66, reported that his store had been broken into more than 80 times since 1967, and that the losses continued despite the recent installation of an alarm system. Bartels “conceded that a business closing in downtown Benton Harbor is an all too familiar story. ‘Everyone knows why, but don’t get into that,’ Bartels told a reporter. Angelo’s Grocery closed their remaining Benton Harbor location near the corner of West Main and 4th Streets on July 21, 1975, having shuttered their other local store two years earlier. “There were at least five hold-ups in the last five years…and the shoplifting was just too much,” said Mrs. Angelo.[54] The Jewel Food Store at 499 West Main Street had closed just two months earlier, after owner Al Jacobsma tried “everything possible to maintain business.”[55] In between, the Shoppers Fair in Benton Township also closed, as its parent company declared bankruptcy.[56] In the article about Angelo’s, one elderly customer shared a common lament: “Where are we going to go for groceries now?” The loss of so many businesses left the residents of Benton Harbor with few options and reinforced the city’s growing segregation.

Ray Wilder’s recollections confirm the personal effects of the changes in the city. “Many of our customers were moving out of town and didn’t come back so often,” he wrote. “The deterioration of Benton Harbor and the riots took their toll on our business, and after a session of unwarranted picketing of the drug store, we finally closed the doors in April 1971.” [57] The public announcement of the closure, scheduled for April 3, 1971, stated only that Wilder, 59, “attributed his decision to close the store to a combination of factors: his age, the economic trend of the times, and the fact that he has had little time off and no vacations in many years. ‘I just don’t feel like starting over,’ he said.”[58] Ray Wilder took significant pride in his good relationships with Black neighbors and customers in Benton Harbor, and the mutual respect had been borne out in a striking way. In September of 1969, the local head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference called for a boycott of Benton Harbor area merchants to press for the implementation of fifteen racial justice initiatives.[59] Specifically exempted from this boycott was a handful of businesses which had cultivated good relationships with the Black community, including Wilder’s Drug Store. Wilder included a copy of the newspaper report on the boycott in his family scrapbook and mentioned these positive relationships elsewhere. Nevertheless, due to what they described as “circumstances beyond our control,” the Wilders joined the many businesses who closed their doors.[60]

Each of the business closures and family relocations was a personal decision. Some were the result of the troubles of parent companies. Some couldn’t afford to maintain aging buildings. Some, like the Wilders, said they had simply worked long enough and were ready for a change. But a common thread ran through them all; whether they thought it was dangerous or they had just moved away and didn’t want to make the trip back, customers were no longer coming to shop in Benton Harbor.

The Data of Decline

The data bear out this perception of increasing segregation and poverty in Benton Harbor. Comparing census data for the years 1960 and 1980 provides a stark statistical picture of segregation and economic hardship in Benton Harbor. According to these data, the population of Berrien County grew by 14.3% between 1960 and 1980.[61] Meanwhile, the population of the city of Benton Harbor shrank by 27.2%. This was the highest rate of decline of any measured area in the northern half of Berrien County. The city of St. Joseph (-18.1%) and adjacent Benton Township (-4%) also declined, but surrounding townships and nearby cities grew. Hagar Township (+39%), Coloma Township (+36%), and Bainbridge Township (+15%) expanded significantly. Lincoln Township more than tripled in population during these two decades, with the 9,058 new residents far exceeding the combined losses of the twin cities (-6,562). Clearly the residents of Berrien County’s cities were getting out of town if they were able. The census data also illustrate the racial aspect of the population shift between 1960 and 1980. Although the city of Benton Harbor’s overall population dropped, the number of Black residents nearly tripled (from 4,846 in 1960 to 12,692 in 1980) while the number of White residents decreased by 86% (from 14,290 in 1960 to 2,015 in 1980). In percentage terms, the city changed from 25.3% Black to 86.3% Black, while twin city St. Joseph, which registered only 93 Black residents in 1960, or 0.8% of their total population, was only 2.4% Black in 1980.

Comparing the economic data from 1960 and 1980 shows the economic disparities that accompanied this growing racial segregation.[62] In 1960, Benton Harbor’s median income of $5,990 was 80.2% of that of St. Joseph ($7,462). This discrepancy grew by 1980 to the point that Benton Harbor ($9,074) had decreased to 59% of that of St. Joseph ($15,151). More concerning yet were the relative poverty levels. In 1980, 38.6% of the residents of Benton Harbor had incomes below the federal poverty line, the highest level of any city in the state. Only four out of Michigan’s 531 cities had a poverty rate over 30%. Benton Township, which surrounds much of the city, was substantially lower at 22.6%. And across the river St. Joseph had just 6.2% of its residents living in poverty.[63] The lines between the haves and the have-nots were clearly drawn, and Benton Harbor had lost.

Attempts to Revive Benton Harbor

Numerous attempts have been made to revive Benton Harbor and bring economic justice to its residents, but none have brought about the necessary change. In 1985, Michigan State University psychology professor John Schweitzer launched the MSU-Benton Harbor Demonstration Project. Conceived as an extension of MSU’s land grant mission, the project was intended to create “a permanent working relationship between Benton Harbor and MSU.”[64] The project spawned the Neighborhood Information and Sharing Exchange (NISE) and the Benton Harbor Community Forum, and a local conference was planned to highlight these and other efforts. However, just a few years later NISE published an editorial in its own newsletter which asked “What part has MSU’s Urban Affairs Department played in the success that we have seen? In our opinion, very little.”[65] The editorial goes on to declare the MSU-BH project to be “dead.” Indeed, of the roughly 60 initiatives that came from this project, only NISE survived more than a few years and very little of the research by students or faculty was formally published. NISE functioned into the 2000s and was able to have a positive impact on the city, but eventually it closed down as well.[66] All that remains today of the MSU-Benton Harbor project is 10.4 cubic feet of records in the Michigan State University archives[67].

In June of 2003, motorcyclist Terrance Shurn died in a fiery crash following a high-speed police chase through Benton Harbor. The city erupted in two nights of violence, during which a dozen people injured and more than a dozen buildings burned.[68] Governor Jennifer Granholm appointed a task force following the unrest to help Benton Harbor get back on its feet. According to the task force’s co-chairman Greg Roberts, this group aimed to be different: “Asking the citizens for recommendations is a major change from previous efforts. Having a governor who pledged to help and has resources to commit are two more differences he cited.”[69] The best of intentions, however, could not overcome decades of mistrust. “People did not really believe the Task Force would listen,” reported Roberts later in the same article. “They felt they would be used. I think that’s why lots of people didn’t participate.”

In April 2010, Joseph Harris was appointed as Emergency Manager of the city of Benton Harbor. The sweeping powers of this position, strengthened in 2011 by Michigan Public Act 4, were intended to allow the Manager to clean up inefficiencies and root out corruption in order to turn the city’s fortunes around. Previously, Kevyn Orr had been appointed to a similar position in Detroit, and “there was a grudging consensus that Mr. Orr’s tenure in Detroit had been a success.”[70] However, Harris and his successor Tony Saunders made little progress in Benton Harbor during the four years they were in power.[71] The tenure of Benton Harbor’s Emergency Managers is now recounted by residents with great disdain.

Another project which was started in 2003 serves as a reminder of why Benton Harbor’s citizens were suspicious of outside attempts to help. In 2001, Whirlpool Corp. hired Marcus Robinson as a diversity consultant. The Harbor Shores Resort development was one of Robinson’s first initiatives and was envisioned as a public-private partnership that would bring a surge of related investment to Benton Harbor. Whirlpool’s support was not solely altruistic, because Benton Harbor’s troubles made it “increasingly difficult for Whirlpool to attract executive talent to the area.”[72] It took five years to secure financing and plan the project, and another three for the first phases of the project to be completed. The golf course was certainly a success; it is the regular host of the KitchenAid Senior PGA Championship, among other events[73].

So far, though, the Harbor Shores project has fallen short of its goal of revitalizing Benton Harbor. Detroit Free Press reporter Keith Matheny, in a report on the city’s recent drinking water crisis, notes that the results have so far been mixed at best: “Harbor Shores unquestionably provides much-needed tax and tourism revenue for Benton Harbor. But it also provides one of the starkest splits of haves and have-nots–within mere blocks of each other–seen anywhere in the country.”[74] And the process of creating the development did little to rebuild the trust of local citizens. Approximately 22 acres of the 74-acre Jean Klock Park were carved out and leased to the Harbor Shores Community Redevelopment Corporation to form three of the course’s eighteen holes. The park is Benton Harbor’s largest public park and the city’s only section of Lake Michigan shoreline. A group of citizens lead by Carol Drake, of the Friends of Jean Klock Park, sued the city to overturn the lease.[75] The judgment in favor of the city was let stand on appeal to the Michigan Supreme Court, and once again Benton Harbor received unwanted nationwide attention for the treatment of its citizens at the hands of outside interests[76].

Further questions

As with any research project, every answer leads to more questions. Some of the areas that could yield more helpful information include the following:

1. A deeper dive into the census data would allow for some more helpful comparisons to Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas, which have been studied in much greater depth than smaller cities and rural areas. Even in 1980, when Berrien County was first considered an SMSA, much of the aggregate data available in the US Census reports was collated only for SMSAs of 250,000 or greater, and the Niles/Berrien SMSA was only 171,276. The research study The State of Black Michigan 1967-2007 provides a wealth of analysis of census and other data, although it also lacks analysis of less-populous areas.[77] How did Benton Harbor compare to other Michigan cities of similar size? How did small towns in Michigan compare to others in the Midwest, particularly other Great Lakes port towns?

2. A thorough history of Benton Harbor should include the House of David religious community. Beginning when founder Benjamin Purnell brought his followers to Benton Harbor in 1906, the sect acquired substantial property holdings and attracted the attention of residents and tourists.[78] While their size and influence had waned by the 1970s, the House of David had a significant effect on the city.[79] Remnants of the organization persist to the present day.[80]

3. Given that urban renewal efforts in Benton Harbor started as early as 1958, when the city had not yet begun to feel the drain of white flight and long-term local businesses were still thriving, why was renewal thought to be necessary in the first place? Did these misguided efforts serve to hasten the city’s decline? The construction of the interstate highway system had a damaging effect on many urban neighborhoods, both with construction and with deleterious effects on adjacent property values. No highway was ever built through Benton Harbor, and the interchange at Lakeshore Drive and Klock Road was demolished a few decades after it was built. But did all of the discussion of highway construction still have a detrimental effect on property values in the city?

4. Due to a variety of issues including construction, funding and staffing, and simply being off-season, some of the key archives for Benton Harbor history were unavailable to me while researching this paper. Time spent at the Morton House Museum, the Heritage Center, the Berrien County Historical Society, and the House of David Baseball & Historical Museum would almost certainly yield much more helpful information.

5. The archives of the MSU-Benton Harbor project may have some ideas worth pursuing, despite that project’s lack of lasting success. The one initiative that lasted, the Neighborhood Information and Sharing Exchange (NISE), published a regular newsletter. Locating an archive of this publication would be helpful to understand why only this organization lasted and what effect it had. It is also likely that individuals involved with NISE still live in the Benton Harbor area and might have additional insights.

6. Finally, what other family accounts like Ray and Edna Wilder’s exist? Like the family of the Wilders, many long-time Berrien County families still live in the area – perhaps their family files or other local collections contain written accounts. There are also area residents who remember this decade, and collecting oral histories would offer valuable insights. Of special interest would be any documents that would give a voice to residents who were not heard in the local press.

Conclusion

In his article “Benton Harbor: After the Fire,” author Mick Dunke summarizes Benton Harbor’s troubles in this way: “The city fell into an ugly cycle. With few people working, the tax base eroded, and public services, including the police force and school system, struggled along with less money. Fewer middle-class people wanted to invest in housing or send their kids to Benton Harbor schools. They moved–and the tax base sank some more.”[81] Those left in the city–a population that was increasingly segregated and impoverished–felt abandoned. And most efforts to correct the long-standing problems either withered away or offered little tangible relief for residents. Nonetheless, while it is easy to get discouraged about the future of the city of Benton Harbor, it is the determined spirit of the people here that offers hope. An understanding of the events and issues that have brought the city to this place will help all those laboring restore Benton Harbor.

Appendix A

This account of the fifteen demands put forth during the 1969 boycott is transcribed verbatim from the News-Palladium article of September 25, 1969, including capitalization and punctuation. It is noteworthy as a document of the issues the Black community faced in Benton Harbor during this decade.

The Benton Harbor chapter of the SCLC listed the following demands to all merchants, with small or large businesses in Benton Harbor and the Fairplain Plaza.

- Play an active role in the community by helping to see that justice, equal employment, and fair representation in the city government prevails for black citizens which will help to bring a better understanding between the races.

- A black Lieutenant on the Benton Harbor police force and crash helmets to be removed except in case of an emergency.

- Segregation of city garbage pickers stopped, plus hiring of more black people in the city’s water department. Also the hiring of some black supervisors in the public work’s department.

- Harbor Towers be integrated according to the population of the city.

- Benton Harbor City Atty. Sam Henderson resign immediately and City Commissioner Charles Gray resign from the fourth ward.

- Laws passed against landlords who overcharge poor black and white people for rent.

- Housing code laws to be enforced on all landlords not just those who don’t have any influence on city hall.

- White people to receive same punishment as blacks for crimes of the same nature.

- Loan institutions to start lending money to poor black and white people of the community.

- More black contractors to be hired by the city and its school system.

- White contractors who don’t have black’s employed to be unable to bid on any contracts for the City of Benton Harbor.

- A recreation center for the young people of the community, sponsored by the city and operated by the people.

- Blacks to be hired by all business in Benton Harbor and Fairplain Plaza.

- All publicity related to crime to be reported objectively on an unbiased opinion.

- At least one black disc jockey on radio stations WHFB and WSJM and that the stations play additional ‘Soul’ music plus programs relating to the black community.[82]

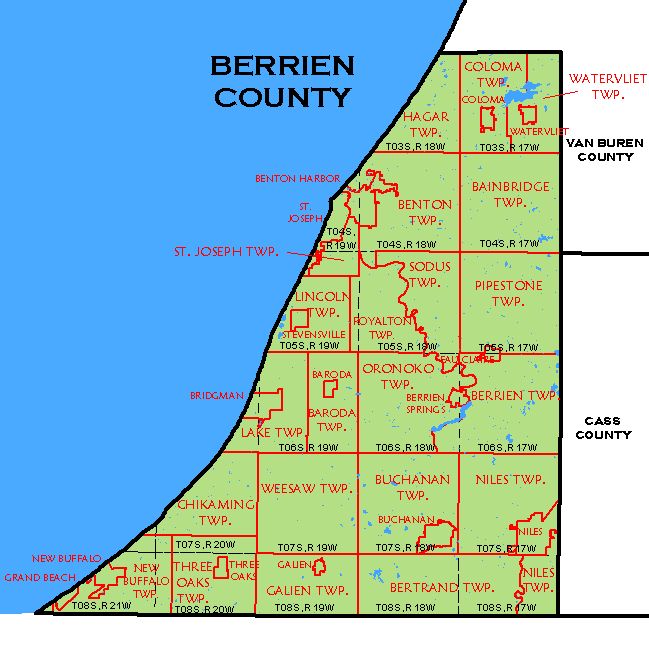

Appendix B: Map of northern Berrien County[83]

Primary Sources

Battle Creek (Mich.) Enquirer

Chicago Tribune

Detroit Free Press

Herald-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Mich)

Herald-Press (St. Joseph, Mich.)

Hillsdale (Mich.) Daily News

New York Times

News-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Mich.)

Coolidge, Orville W. A Twentieth Century History of Berrien County Michigan. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1906.

Kozlowski, James C. “Golf Lease Consistent With Public Purpose Gift?” Parks & Recreation, July 2011. Gale General OneFile.

McClure, Robert. “Heart Of Michigan Park Sacrificed For Private Golf Course.” Investigate West, June 11, 2012. https://www.invw.org/2012/06/11/benton-harbor-michigan-1280/.

Michigan Municipal League. “Handbook for Charter Commissioners: Resource Materials for Village Charter Revision.” Internet Wayback Machine. Accessed March 18, 2023. http://www.mml.org/pdf/mr/mr-organization-city-village-gvt.pdf.

Morton, J.S. Reminiscences of the Lower St. Joseph River Valley. Benton Harbor, MI: Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1930.

Polk’s Benton Harbor (Michigan), City Directory: Including St. Joseph. Detroit, MI: R.L. Polk and Company, 1965.

Polk’s Benton Harbor (Michigan), City Directory: Including St. Joseph. Detroit, MI: R.L. Polk and Company, 1975.

Rakstis, Ted. Benton Harbor Centennial Program and Picture Album. Benton Harbor, MI: Benton Harbor Centennial Association, 1966.

Seamster, Louise. “When Democracy Disappears: Emergency Management in Benton Harbor.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 15, no. 2 (2018): 295–322. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X18000255.

Thomopoulos, Elaine Cotsirilos. St. Joseph and Benton Harbor. Images of America. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2003.

United States Bureau of the Census. Census of Population, 1960, Michigan. Report PC(1)-24 A-B-C-D, 4 vols. Washington: U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1961.

United States Bureau of the Census. 1980 Census of Population and Housing. Summary Characteristics for Governmental Units and Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas: Michigan. Washington, D.C.: U.S.Govt. Printing Office, 1982.

United States Bureau of the Census. 1980 Census of Population. Volume 1. Characteristics of the Population. Chapter A. Number of Inhabitants. Part 24. Michigan. U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1982.

Willey, O. S. “St. Joseph and Benton Harbor, Michigan.” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 24, no. 281 (November 1869): 334.

Zerler, Kathryn Schultz, Peggy Lyons Farrington, and Harold A. Atwood. On the Banks of the Ole St. Joe: A Selected History of St. Joseph and Benton Harbor, Michigan. 1st ed. St. Joseph, Mich., St. Joseph Today, 1990.

Secondary Sources

Bradbury, Katharine L., Anthony Downs, and Kenneth A. Small. Urban Decline and the Future of American Cities. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution, 1982.

Briggs, Shay Kathleen. “Exit 33: The Economic Decline of Benton Harbor, Michigan.” MA Thesis, Western Michigan University, 2009.

Darden, Joe T., Curtis Stokes, and Richard Walter Thomas, eds. The State of Black Michigan, 1967-2007. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2007.

Ewalt, Joshua P. “Oscillating Scale and Articulating Regions: Power Geometries and Multi-Scalar Publics in People’s Tribune’s Coverage of Benton Harbor, Michigan.” Communication and the Public 7, no. 1 (2022): 27–39.

Kotlowitz, Alex. The Other Side of the River: A Story of Two Towns, a Death, and America’s Dilemma. 1st ed. New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1998.

Kotlowitz, Alex. “The Other Side of the River, Revisited.” New Yorker, June 11, 2021.

Lemann, Nicholas. The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America. 1st Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1992.

Love, Hanna, and Tracey Hadden Loh. “The Geography of Crime in Four U.S. Cities: Perceptions and Reality.” Future of Downtowns Project. Brookings Institution, April 3, 2023. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-geography-of-crime-in-four-u-s-cities-perceptions-and-reality/.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press, 2003.

Myers, Robert C. Greetings from Benton Harbor. Historic Photobook Series. Berrien Springs, MI: Berrien County Historical Society, 2011.

Seamster, Louise. “Race, Power and Economic Extraction in Benton Harbor, MI.” PhD dissertation, Duke University, 2016.

Sugrue, Thomas J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. First Princeton classics edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Wilson, William J. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Second edition. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

-

Fister Real Estate Advertisement, News-Palladium, March 23, 1966. ↑

-

The author is married to Ray and Edna Wilder’s granddaughter. ↑

-

These data, discussed in detail below, is taken from Polk’s Benton Harbor (Michigan), City Directory: Including St. Joseph (Detroit, MI: R.L. Polk and Company, 1965 & 1975). ↑

-

See “The Basic Nature and Extent of Urban Decline” in Bradbury, Downs, and Small, Urban Decline and the Future of American Cities, pp. 4-7. ↑

-

Despite their small size, Benton Harbor and St. Joseph are properly referred to as cities, a specific legal term in the state of Michigan which I address in the Methodology section. ↑

-

In addition to the local coverage cited in this paper, in-depth articles on Benton Harbor have appeared in the Chicago Tribune, the New York Times, Time, the New Yorker, The Economist, and The New Republic, as well as numerous trade magazines discussing local industries of specific interest to their readers. For example, see “Invisible Lines,” Time Magazine, March 2, 2020, and “Whirlpool Corporation Leases Kay Building in Downtown Benton Harbor,” Business Wire, July 10, 2003. ↑

-

Orville W. Coolidge, A Twentieth Century History of Berrien County Michigan, 1906. For Benton Harbor’s history, see pp. 232-243. ↑

-

Alex Kotlowitz, The Other Side of the River: A Story of Two Towns, a Death, and America’s Dilemma, 1st ed (New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 1998), 258. ↑

-

Louise Seamster, “Race, Power and Economic Extraction in Benton Harbor, MI” (Dissertation, Durham, NC, 2016), 5. Seamster makes a crucial geographical error here: The Paw Paw River marks the northern boundary of Benton Harbor. It is the St. Joseph River that divides it from the city of St. Joseph. ↑

-

Seamster, 272. ↑

-

Shay Kathleen Briggs, “Exit 33: The Economic Decline of Benton Harbor, Michigan” (M.A. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, 2009), 1. ↑

-

Briggs, 1. ↑

-

Robert C. Myers, Greetings from Benton Harbor, Historic Photobook Series (Berrien Springs, MI: Berrien County Historical Society, 2011), 9. ↑

-

Thomas J. Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), xxvii. ↑

-

Sugrue, 270. ↑

-

William J. Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy, Second edition (Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 33. ↑

-

Nicholas Lemann, The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America, 1st Vintage Books ed (New York: Vintage Books, 1992). ↑

-

Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton, American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass (Harvard University Press, 1998), 8. ↑

-

“Today Our Name Changes to ‘The Herald-Palladium,’” Herald-Palladium, February 2, 1975. ↑

-

For example, see the identical front pages of the September 1, 1966 editions. An interesting study could be made of any differences between the two papers that do exist. ↑

-

Such as J.S. Morton, Reminiscences of the Lower St. Joseph River Valley and Catherine Moulds, Chips Fell in the Valley. ↑

-

Zerler, Farrington, and Atwood, On the Banks of the Ole St. Joe. ↑

-

In 1960, SMSAs were centered on cities over 50,000, and the nearest such city (Kalamazoo) is fifty miles away. See 1960 Census of Population: Selected Area Reports: Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas, “1960 Census of Population: Selected Area Reports: Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas” (U.S. Govt. Printing Office, 1963). ↑

-

See Appendix B for a map of Berrien County and the Benton Harbor/St. Joseph area. ↑

-

The 2020 U.S. Census lists several Michigan cities with populations of less than a thousand. (https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/MI/POP010220) ↑

-

Michigan Municipal League, “Handbook for Charter Commissioners: Resource Materials for Village Charter Revision.” ↑

-

For example, see “Greater Benton Harbor” (News-Palladium, May 2, 1944) and “Supervisors Table Fairplain Annex Vote” (Herald-Press, March 15, 1965). ↑

-

Joshua P. Ewalt, “Oscillating Scale and Articulating Regions: Power Geometries and Multi-Scalar Publics in People’s Tribune’s Coverage of Benton Harbor, Michigan,” Communication and the Public 7, no. 1 (2022): 27–39, 29. ↑

-

Ewalt, 32. ↑

-

Orville W. Coolidge, A Twentieth Century History of Berrien County Michigan (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1906), 232. ↑

-

O. S. Willey, “St. Joseph and Benton Harbor, Michigan,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 24, no. 281 (November 1869), 334. ↑

-

Robert C. Myers, Greetings from Benton Harbor, Historic Photobook Series (Berrien Springs, MI: Berrien County Historical Society, 2011), 9. ↑

-

“B.H. Urban Renewal Wins!,” News-Palladium, April 7, 1964. ↑

-

“B.H. Condemnation Suits Are Filed,” News-Palladium, January 10, 1967. ↑

-

“Benton Harbor General Development Plan” (U.S. Dept. of Commerce, 1989), 12. ↑

-

Ted Rakstis, Benton Harbor Centennial Program and Picture Album (Benton Harbor, MI: Benton Harbor Centennial Association, 1966), 40. ↑

-

For one example, see Tom Brunprett, “New I-94 Penetrator Concept Proposed,” News-Palladium, October 10, 1969. ↑

-

“Police Disperse Rock-Tossing Teen Gang,” News-Palladium, August 29, 1966. ↑

-

“Officials Issue Peace Appeal,” News-Palladium, August 30, 1966. ↑

-

“Boy Dies of Bullet Wound,” News-Palladium, August 31, 1966. ↑

-

“Police Clear Man Arrested in Slaying,” News-Palladium, September 1, 1966. ↑

-

“Police, ‘Peace Squads’ Restore Quiet To City,” News-Palladium, September 1, 1966. ↑

-

“Find Benton Harbor Widow Slain in Home,” Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1967. ↑

-

“Three Boys Accused of Murder,” News-Palladium, October 25, 1967. ↑

-

“Benton Supervisor Vows Help In Fighting Crime,” News-Palladium, October 25, 1967. ↑

-

“Mrs. Peapples, 83, Found Dead,” News-Palladium, October 21, 1967. ↑

-

News-Palladium, May 15, 1970. ↑

-

News-Palladium, May 15, 1970 ↑

-

Polk’s Benton Harbor (Michigan), City Directory: Including St. Joseph (Detroit, MI: R.L. Polk and Company, 1965 and 1976). ↑

-

“A Great Store Says ‘Good Bye’ to Benton Harbor (Advertisement),” News-Palladium, August 19, 1965. ↑

-

“BH Store Will Close Its Doors,” News-Palladium, March 12, 1969. ↑

-

“Landmark BH Chinese Food Center Closing,” News-Palladium, April 28, 1973. ↑

-

Jim Shanahan, “Familiar Story–BH Firm Closing,” News-Palladium, June 11, 1974. ↑

-

Steve Sager, “Angelo’s Downtown Store Closing After Half-Century,” Herald-Palladium, July 22, 1975. ↑

-

“Jewel To Close BH Food Store,” Herald-Palladium, April 10, 1975. ↑

-

“Shoppers Fair Here to Close Its Doors,” Herald-Palladium, June 17, 1975. ↑

-

Ray Wilder, “My Story” p.9. ↑

-

“Wilder’s Drug Store Will Close April 3,” Herald-Press, March 27, 1971. ↑

-

“Bishop Calls For Black Boycott of BH Stores,” News-Palladium, September 25, 1969. See Appendix A for the list of demands from the SCLC. ↑

-

“Due to Circumstances Beyond Our Control (Advertisement),” News-Palladium. March 26, 1971. ↑

-

Population data taken from United States Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1960, Michigan, Table 20 and, 1980 Census of Population. Volume 1B. General Population Characteristics. Part 24. Michigan., Table 14. ↑

-

Economic data taken from United States Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1960, Michigan, Table 67 and 1980 Census of Population and Housing. Summary Characteristics for Governmental Units and Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas: Michigan, Table 4. ↑

-

The 1960 census does not include statistics on poverty levels, as the first official poverty measure was developed in 1963. ↑

-

William F. Ast III, “MSU-BH Link Is Growing, Professor Says,” Herald-Palladium, November 12, 1985. ↑

-

Quoted in William F. Ast III, “NISE Says MSU Has Given Up on BH Project,” Herald-Palladium, December 12, 1989. ↑

-

For one recounting of NISE’s impact, see Jim Dalgleish, “NISE President’s Goal Is To Change Community,” Herald-Palladium, July 21, 2002. The last mention of the organization in the local press is in 2003. ↑

-

A finding aid is posted at https://archive.lib.msu.edu/uahc/FindingAids/ua3-23.html. (retrieved April 21, 2023) ↑

-

Jodi Wilgoren, “Fatal Police Chase Ignites Rampage in Michigan Town,” New York Times, June 19, 2003. ↑

-

Lynn Stevens, “Task Force Readies Report For Governor,” Herald-Palladium, October 8, 2003. ↑

-

Julie Bosman and Monica Davey, “Anger in Michigan Over Appointing Emergency Managers,” New York Times, January 26, 2016. ↑

-

The process and results are detailed in Louise Seamster, “When Democracy Disappears: Emergency Management in Benton Harbor,” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 15, no. 2 (2018). ↑

-

This description of the Harbor Shores development project is taken from Jonathan Mahler, “Now That the Factories Are Closed, It’s Tee Time in Benton Harbor, Mich.,” New York Times, December 15, 2011, sec. Magazine. ↑

-

https://www.harborshoresresort.com/golf/srpga/, retrieved 4/8/23 ↑

-

Keith Matheny, “Dozens of Major Water Violations Stretching Back to 2018,” Detroit Free Press, November 14, 2021. ↑

-

James C. Kozlowski, “Golf Lease Consistent With Public Purpose Gift?,” Parks & Recreation, July 2011. ↑

-

Robert McClure, “Heart Of Michigan Park Sacrificed For Private Golf Course,” Investigate West, June 11, 2012. ↑

-

For example, see the analysis of census data in chapter 6, “The Housing Situation of Blacks in Metropolitan Areas of Michigan,” Joe T. Darden, Curtis Stokes, and Richard Walter Thomas, eds., The State of Black Michigan, 1967-2007 (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2007), 113-128 ↑

-

“The Fall of the House of David,” The Independent (1922-1928) 120, no. 4049 (January 7, 1928). ↑

-

Piet Bennett, “House of David Clings to Belief That Man Will Perish,” Hlllsdale Daily News, May 6, 1971. ↑

-

John Carlisle, “No Alcohol, No Problem: House of David, a Celibate Commune in West Michigan, Generates Nostalgia a Century Later,” Battle Creek Enquirer, November 19, 2016. ↑

-

Mick Dumke, “Benton Harbor: After the Fire,” Colorlines, Spring 2005, 47 ↑

-

“Bishop Calls for Black Boycott of BH Stores,” News-Palladium, September 25, 1969. ↑

-

Michigan Dept. of Natural Resources. Map of Berrien County, accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.dnr.state.mi.us/spatialdatalibrary/pdf_maps/glo_plats/berrien/berrien.htm ↑