Reproducing Morality: Dr. Minnie Love, Social Movements, and Eugenics in Early Twentieth Century Denver

By: Summer Carper

In October of 1922, Dr. Minnie C. T. Love read her public health report on the Denver Venereal Disease Clinic and the State Detention Home for Women at the annual meeting of the Colorado State Medical Society. Venereal diseases were “a menace to public health.” They “threaten[ed] the lives of unborn children, which disrupt[ed] homes, fill[ed] our insane hospitals, feeble-minded institutions, our prisons and reformatories,” according to Love. This exclamation on the repercussions of venereal diseases in addition to the medical and moral reform work Love proposed revealed the way she understood public health. For Dr. Minnie Love, venereal disease and public health were key to her moral goals. “The infectious luetic [syphilitic] [was] one of the greatest menaces to the race,” Love concluded in the report.[1] As venereal diseases were a threat to society and “the race,” addressing them was the first step of Dr. Minnie Love’s lengthy medical, philanthropic, and political career.

Amidst the Progressive Era, four important social and public health movements emerged: the social hygiene movement, the eugenics movement, the second rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and the early birth control movement. The social hygiene movement centered on sexual morality and eradicating venereal disease while eugenics, a global movement and ideology, rose to prominence on the premise of improving the human race through reproduction of “fit” families.[2] The second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan idealized white Protestant morality and Americanism, thereby demonizing Black, Jewish, and Catholic peoples. Slightly later, the early birth control movement advocated for more access and education of birth control options. Activists and members of these movements across the country attempted to shape society and public health with interconnected – explicit and/or implicit – goals of protecting and expanding the white race.

In Denver, Colorado, intersections of these four movements and organizations appeared in turn of the century social, medical, and political spaces. Prominent female physician, Minnie C. T. Love is representative of this twentieth century crossroads. Educated at Howard University in the late 1880s, one of the only medical schools open to women, Love was enthusiastic about women’s and children’s health. She moved to Denver in 1892 and received her Colorado medical license in 1893. Immediately, Love became involved in women’s social and philanthropic clubs and medical politics as a member of state boards like the Board of Charities and Corrections and as an elected member of the Colorado House of Representatives. Love promoted social hygienic goals of morality and treatment of venereal disease as well as eugenic values of improving the human race through sterilization of “unfit” populations. When the Ku Klux Klan rose in Denver, she became a member of the Women’s KKK chapter, modeling the Klan’s focus on political power to protect the traditional morality of white Protestants. Her eugenic contraceptive strategy notwithstanding, Love was adamantly against birth control education and access. Overall, Dr. Minnie C. T. Love’s history provides a glimpse into the social, medical, and political ideologies of the early twentieth century.

As an early female physician, Minnie Love had a complicated and largely unexplored history; historians of the four movements often relegated her to a small biographical section or footnote. Scholars like Robert Goldberg mention Love in their research of the Denver Ku Klux Klan as a renowned female counterpart to KKK Grand Dragon Dr. John Galen Locke.[3] One of the main focuses of scholarship on Love, however, has been her stance on reproductive access. It was not until recently that a historian challenged the seminal study, Hooded Empire by Goldberg on the claim that Love was a birth control advocate. In 1925, Love proposed a House bill titled, “A bill for an Act to regulate the manufacture, sale and distribution of contraceptives and providing a penalty for the violation of this Act.” Many historians have cited this House bill as her encouragement of access to birth control, in a similar fashion to famous birth control movement founder, Margaret Sanger. [4] Historian Jacqueline Antonovich in “White Coats, White Hoods” was the first scholar to challenge this claim.[5] This paper will build upon Antonovich’s assertion that Love was staunchly against birth control and disagreed with the work of Margaret Sanger. While historians of the birth control movement and Sanger have not argued either way, new interpretations of evidence reveal Love’s opposition to birth control.

Additionally, scholars of each of the four movements are only now beginning to connect the pieces of each movement’s motivations and actions. While contemporary scholars often noted that social hygiene, the Ku Klux Klan, and birth control had eugenic underpinnings, modern historians have separated these movements.[6] This paper will bring these concealed eugenic principles back into view, revealing how the four social movements intertwined. Ultimately, there is a large missing puzzle piece in the histories of social, medical, and political efforts of the social hygiene, eugenics, Ku Klux Klan, and birth control movements.

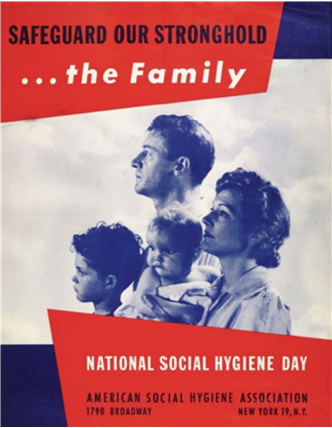

Moreover, these four social movements and ideologies did not exist in a vacuum. All of these movements were strongly associated with each other and arose at the turn of the century spurred by cultural changes to sexuality and gender. Venereal diseases became a larger and more recognizable issue because fear of prostitution and acceptance of free sex ideas grew, leading to the establishment of the social hygiene movement to protect the (white) family and morality. Furthermore, the common medical belief at the time claimed venereal disease led to insanity and feeblemindedness. Eugenicists targeted mental “degenerates,” the feebleminded, lower-class families, and people of color to improve the superior white race.[7] Cultural changes to sexuality and gender resulted in fear for traditional morality, thus inspiring different organizations to try to protect Victorian-based morals. Like the social hygiene movement, the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s built upon this growing concern for traditional morality and exacerbated the issue, feeding into eugenic values. Likewise, the birth control movement benefited and worked with eugenicists to advocate for who should procreate.[8] Overall, the four social movements united and influenced social, medical, and political ideologies. Fundamentally, all of these movements had similar racist and classist goals of protecting the white, upper or middle-class family’s morality and propagating the white race, in turn medically and politically controlling the reproduction of the “unfit” through multiple different avenues. In Denver, Dr. Minnie Love sought to protect the family, traditional morality, and the race, representing the intersection of social hygiene, eugenics, the Ku Klux Klan, and the early birth control movement.

Medicine and Society

Minniehaha Cecilia Francesa Tucker was born on November 9th, 1855, in La Crosse, Wisconsin to a branch of the Roosevelt family. Little is known about her until her adulthood in the late nineteenth century. In 1876, Minnie married Charles Guerley Love with whom she would have three children. Her story truly began, though, in 1887 with her graduation from Howard University where she was the only white graduate – an interesting beginning for a Klanswoman. In the mid-nineteenth century, medical schools slowly began to accept women, though the first ones to do so were Black colleges and universities. After graduation, Minnie and Charles Love would travel for the next few years, allowing Minnie to take classes in London and New York before they settled in San Francisco for a brief time. In the 1890s, the two moved to Denver where they would remain until Charles’ death in 1907 and Minnie’s death in 1942.[9] Minnie began both her medical career at the Florence Crittenton Home and philanthropic work through women’s clubs soon after their move to Denver.

The American West provided many opportunities for women before the East: suffrage, political office, and medical careers. Colorado women and other western residents gained suffrage before the turn of the century, years before other states and at the federal level. Women and allies passionately worked for suffrage in the last few decades of the nineteenth century through women’s clubs and other organizations. The women’s club movement began in 1868 as an intellectual or literary group for women though they quickly took on philanthropic and suffrage work in the 1870s and 1880s. Women’s historian Gail Beaton described club members as white, middle and upper-class married women who endeavored to solve social condition problems.[10] Once Colorado women became enfranchised, they elected women to political office where they built civic influence and community reforms. For example, one major effort they worked towards, including Love, was prohibition. Overall, similar to women in medicine and political office, women involved in philanthropic organizations focused on women and children in their work.

This early adoption of women’s suffrage reflected wider opportunities for women in careers like medicine. According to Love’s history of women practitioners published in the Colorado Medical Journal, the first woman to graduate from a Colorado medical school was Eleanor Lawney, in 1887, before she and other women could vote.[11] Historian Kimberly Jensen explained the impact of suffrage and the rise of women physicians as the turning point in the medical community. The West was home to the largest percentage of women physicians in the United States, 4.8 percent, with Colorado as the fourth highest state percentage. While this and the early passage of suffrage may have provided the image of a “freer climate,” structural biases still hindered women in the West.[12] Women in medicine nevertheless fought for children and women-oriented public health initiatives.

Love received her medical license in 1893 and she promptly began her influential medical career in Denver, Colorado. While Love worked at the Florence Crittenton Home, a home primarily for unwed mothers, she also joined the male-dominated State Medical Society.[13] Her first speech in 1897 at the Twenty Seventh Annual Convention, “Electricity in Diseases of Women,” followed by “The Lying-In Chamber,” as well as “Puerperal Infection” for the Denver Clinical Society reveal that from early on in her career, women and maternal health were her main priority.[14] As she earned a name for herself, she was the first woman appointed to the State Board of Pardons, Charities, and Corrections (1893) and also served on the State Board of Health (1906-1912). Her social and philanthropic work, in which she focused on suffrage and public health, augmented her medical career.

Love was a busy woman at the turn of the twentieth century. During her initial years in Denver, not only was she expanding her medical influence but also her social organization memberships. A card-carrying member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the Women’s Club of Denver, and the Equal Suffrage Association, Love fought for women’s suffrage, prohibition, and other reform goals.[15] In the Women’s Club, Love served as a leader of various reform or legislative departments as well as the City Improvement Society, which was “devoted to the betterment of our city” through ordinance enforcement and education because “sanitation [was] greater than medicine.”[16] Furthermore, Love lectured on various topics for Women’s Club meetings and conventions, reflecting her growing prestige.[17]

Whether in women’s clubs, political offices, or medical careers, women served important roles in aiding women’s rights and healthcare. To do this, women established group homes for unmarried pregnant women and prostitutes like the Colorado Cottage Home and Florence Crittenton Home where Love served as the house physician for twelve years. In the Progressive Era, criminality and delinquency was a major concern, leading the Colorado legislature to establish the State Home and Industrial School for Girls in 1887. Anxiety about poor women, criminality, and sexuality led to the Industrial School housing women and girls in order to treat their immorality. This vision aligned perfectly with Love’s efforts, and she served on the Board of Control for the school from 1896 to 1902. An autographed book in the Love archival collection reflects her impact on the girls at the State Industrial School.[18]

For children, clubwomen, physicians, and politicians created children’s aid institutions like the State Home for Dependent and Neglected Children. Additionally, in 1897, Love founded the Babies Summer Hospital, a tent hospital on 18th Avenue and York St. Operating an outdoor hospital was difficult, and in 1898 the Spanish-American War forced medical efforts to shift. Love and other female physicians, though, knew there was a need for a permanent children’s hospital; what started as a tent hospital would become the Children’s Hospital of Colorado. After years of effort, in 1910 the Children’s Hospital opened in a physical building to provide medical care to all children who needed it.[19] These efforts speak to the significance of Love and other female physicians’ work for women and children. Furthermore, this foundation of women and children initiatives would be a partial inspiration for the protection of family, morality, and the race the social hygiene, eugenics, and KKK movements would assume.

As Love grew in medical and political influence, social rules about sexuality were changing, becoming less regulated and thus a moral dilemma for reformers to rally behind. Scholar Kristen Luker described the Progressive Era as a “watershed period” where society transformed from rural “familial patriarchy” to urban “social patriarchy.” This transition is most recognizable in the regulation of prostitution and sexuality where the social hygiene and eugenics movements sought to control the mores of sexuality. Social hygiene in particular, Luker argued, brought together two powerful groups – physicians and women moral reformers. Legal statutes and community leaders had defined acceptable sexual behavior and the boundary of this behavior – prostitution – when smaller communities of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries could enforce these boundaries. With the expansion of the industrial economy and far-reaching American communities, gender divisions, sexuality, and family life evolved. Moreover, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Americans delayed marriages with women seeking careers over families, having fewer children, and more divorces. [20] This failure of the American family to reproduce for “the race” was a seedling for social hygienists, eugenicists, and the KKK.

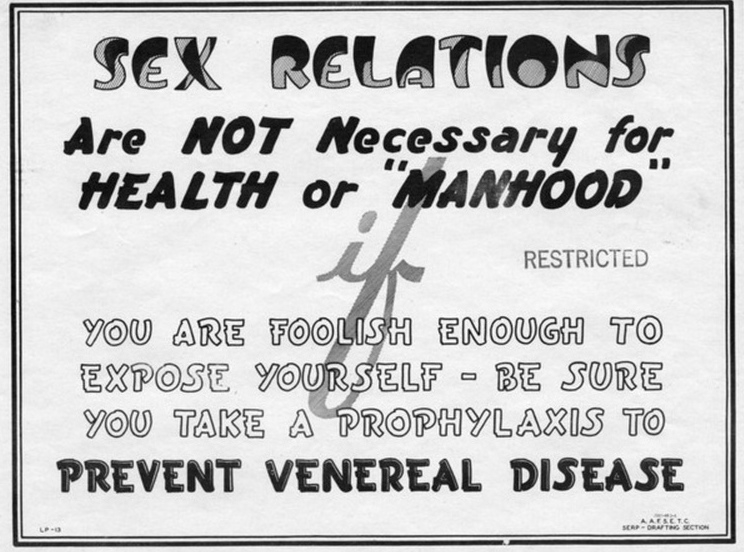

![]()

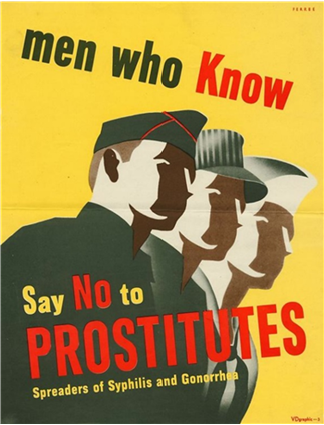

As control and attention on acceptable sexual behaviors morphed, prostitution became a focal point for moral and purity reformers. With prostitution in the spotlight, medical research on venereal diseases revealed the differences between chancroid, gonorrhea, and syphilis and that syphilis caused a multitude of other issues like paralysis and insanity – a fact that would bind social hygienists and eugenicists together.[21] Beginning in the late nineteenth century, venereal disease became both a serious public health concern and a scapegoat for cultural changes. Historian Allan Brandt stated that venereal diseases became a “palpable sign of degeneration” and for Progressive physicians a danger to the “foundations of Victorian, child-centered family.”[22] The belief in non-sexual transmission compounded the threat to families as venereal diseases, namely syphilis, could infect anyone, even respectable upper and middle-class individuals. A State Board of Health Division of Venereal Disease chart from 1922 in Love’s archival collection reveals that around sixteen percent of patients were “innocent victims.”[23] The “general and ominous collapse of late-Victorian morality” Brandt referenced in No Magic Bullet, prompted public health officials like Minnie Love to propose and pass legislation to combat the scourge.[24] One-fifth of the bills Love proposed in her years as a Colorado representative dealt with venereal diseases. These included bills to create a state-run institution for women suffering from venereal diseases, a state board of health division devoted to venereal disease, and a bill criminalizing the infection of another person through intercourse.[25]

![]()

![]()

While Love adopted ideals of protecting traditional morality, she also began promoting eugenic values. Building off new scientific understandings of heredity, eugenics gained popularity in the early twentieth century with the most explicit goal of idolizing the potentially perfect race. The word “eugenics” originated from Francis Galton, an English scientist studying intelligence and inheritance in 1883, though the traditional notion of eugenics took root in the early years of the twentieth century. Eugenics at the turn of the century pursued improving the race through positive eugenics targeting the “fit” (education) and negative eugenics targeting the “unfit” (segregation and sterilization). The categories of fit and unfit evolved over the century, beginning with intelligence and physical fitness but slowly incorporating race and class. Intelligence or lack thereof had many medical terms: idiot, lunatic, moron, insane, or feebleminded; disabilities like blindness, deafness, schizophrenia, and epilepsy also relegated individuals into the “unfit” categorization.[26] Lower-class and people of color also became targets as the concept of the race narrowed to white, middle- or upper-class standards.

Positive and negative eugenic efforts sought to improve the race in vastly diverse ways. Positive eugenics, for example, focused on education and promotion of reproduction of fit families. Positive eugenicists enacted this through things like Better Baby Contests and education on heredity. In Denver, female physician and eugenicist, Dr. Mary Elizabeth Bates, and the Western Stock Show hosted Better Baby Contests. Conversely, segregation through institutionalization and forced sterilizations prevented the procreation of unfit populations under negative eugenics. Minnie Love supported eugenic doctrine for the majority of her career, especially the sterilization of “moral degenerates.” She first publicly announced her support of sterilization in a 1903 speech for the Colorado Medical Society that Colorado Medicine reprinted the same year. In “Criminal Abortion,” Love rejected the practice of abortion, instead, she suggested “limit[ing] the production of moral degenerates” by “separating or sterilizing the feeble-minded and idiots, and those hopelessly insane and epileptic” in addition to “incarcerat[ing] for life male and female confirmed criminals.”[27] Social hygienists, Klansmen, and birth control advocates often supported these eugenic ideologies with the same underlying goal.

Eugenics spread across the United States with various levels of support and legality. In Colorado, eugenic doctrine was a common underpinning of many community reforms. For public health advocates like Minnie Love, eugenics served as a means to enact their goals of community reform. Her speech and article, “Criminal Abortion” in which she argued sterilization was the solution to abortion and the procreation of degenerates, reveals that eugenic thought in Colorado spread early in the Eugenics Movement. In fact, this speech in 1903 was years before the first state passed a sterilization law.[28] Though Colorado legislators such as Love attempted four separate times to legalize sterilization of institutionalized mental patients, they were never successful.

Compared to thirty other states that did have some form of eugenic sterilization laws, Colorado was a minor player in the eugenics movement. The first evidence of sterilization in the legislature was H.B. 179 “to permit operations for prevention of procreation” and S.B. 128 “operations for the prevention of procreation” in 1913. Love proposed the second effort in 1925, H.B. 60 “to prevent procreation of idiots, epileptics, imbeciles and insane persons,” though it too did not pass. After Love left office, another endeavor in 1927 nearly became law. H.B. 509 “authorizing the sterilization of certain persons” passed both levels but Governor Billy Adams ultimately vetoed it. The final effort in 1929 of the same name passed in the House but the Senate indefinitely postponed it. [29] Eugenics, regardless of legality, was still a prevalent scientific, cultural, and medical philosophy.

Eugenics was such a prevalent ideology that unwritten policies of sterilization were common in Colorado institutions. The story of Coloradan Lucile Schreiber’s coercive sterilization highlights this practice.[30] A childhood of uncontrolled energy, running away, and stealing led young Lucile Schreiber to many Colorado institutions including Catholic group homes, the Colorado Psychopathic Hospital, the State Industrial School for Girls, and the Colorado State Hospital. A feebleminded diagnosis in 1933 altered the course of her life, eventually leading to her sterilization in 1942 at the hands of Dr. Irving Schatz of the Colorado State Hospital.[31] Calling her loss of reproductive capabilities “sexual murder,” Lucille went to court in 1958 against the hospital and the superintendent, though the court ultimately ruled in favor of the Colorado State Hospital.[32] Lucile Schreiber’s story demonstrates that Colorado’s unwritten policies of sterilization led to forced surgery even without legal authority and that eugenic thought prevailed in the state throughout the first half of the twentieth century.[33]

The threat of venereal diseases on Victorian family life and morality as well as the rise in hatred towards the mentally ill – and the resulting threat to the race – required social hygienists to support eugenics. Dr. Donald Hooker, a Johns Hopkins educated physician and social hygienist, wrote in 1924, “venereal disease, that blot of tragedy on our social life which has motivated this great moral awakening,” could be controlled by social hygiene and the “guardians of the germ-plasm of the future.”[34] Hooker’s words echoed the language of eugenicists who sought to protect the “germ-plasm” and were similar to nurse Lavinia Dock who said venereal diseases “prey[ed] upon the national stock,” leading her to argue heredity and eugenics should be taught to parents.[35] Eugenicists, as described by Hooker, centered on the procreation of the unfit and overlapped with social hygienists in the concern of venereal disease and the feebleminded who “procreate[d] rapidly, and [were] a many-sided danger to the community.”[36] Medical professionals like Hooker and Dock reveal the inner workings of social hygiene and eugenics in protecting the race, though they had different methodologies of doing so.

At the turn of the century, the first social movements to arise that had ostensible moral goals yet internally advocated protection of the race were social hygiene and eugenics. Across the nation, community and state organizations flourished in defense of the family and in 1914 coalesced into the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA). ASHA combated venereal disease through testing, education, and legislation for premarital exams. Promoted by both social hygienists and eugenicists, premarital exams sought to prevent the spread of venereal disease within marriage. Colorado was one such state to pass a legalized premarital exam in 1939.[37] Eugenicists founded organizations at local, state, and national levels determined to spread the scientific knowledge of how to improve the human race. The Progressive Era witnessed extreme changes to social and cultural norms, especially regarding sexuality. These changes incited fear for Victorian and traditional models of acceptable sexual behavior, family life, and morality. Social movements that arose in the early twentieth century were reactions to these changes; each movement took on surface level objectives in protection of the intangible race.

Moral Politics and Reproduction

Dr. Minnie Love, inspired by her medical and philanthropic career thus far, understood that her goals of social hygiene, eugenics, and public health needed political backing. In 1920, Love ran for the office of Colorado House of Representatives for the city and county of Denver. That November, she received her Certificate of Election for the Secretary of State.[38] In office, Love pushed for bills centered on women, children, and public health. Most notably, she proposed H.B. 9 for the creation of the State Hospital and Training School for Women, H.B. 33 to criminalize the knowledgeable spread of venereal disease, H.B. 145 for “social delinquents” to be committed to institutions, H.B. 357 and 562 regarding food and drug safety, as well as numerous bills to make appropriations for the State Detention Home and State Home for Dependent and Neglected Children.[39]

Historian Jacqueline Antonovich argued in “White Coats, White Hoods” that physicians in the early twentieth century drew from eugenics, contraception, abortion, sexual morals, and science to engage in “reproductive surveillance.” This surveillance connected social movements rooted in morality and sexuality in order to shape political and social policies.[40] Medicine and science in the early twentieth reflected and expanded social anxieties of the time, allowing an examination of medical politics to speak for the social anxieties and vice versa. While Antonovich referred to “reproductive surveillance,” physicians, politicians, and social movement followers did more than just surveil, they actively controlled; thus, medical and/or political reproductive control is a more apt phrase. Ultimately, the controlling of bodies and reproduction served eugenic purposes while upholding moral and racial guidelines set by social hygienists, eugenicists, Klan members, and birth control advocates.

The Ku Klux Klan, especially, undertook efforts to “medically police bodies,” according to Antonovich, to force the conformation of society to the Klan’s “racial and reproductive ideologies.”[41] The Klan’s goals attracted physicians, nurses, and public health officials who had similar goals to Dr. Minnie Love. As public health was already a major concern to Colorado state and local governments, the Klan’s rise in political power mirrored its rise in medical authority. Though Denver voters did not reelect Minnie Love to the Colorado House of Representatives in 1922, the Ku Klux Klan helped her get reelected in 1924. Together, the Klan and public health officials like Love would seek to medically and politically control reproduction.

The Ku Klux Klan that rose to power in the 1920s (1921-1925) in Denver and other cities across the country did so on a platform of addressing issues through politics. Though the Klan had a short rise and fall in influence, the 1920s political scene was emblematic of the Klan’s ideology. Riding on the social changes in twentieth century America, the Klan sought to protect Americanism and the old moral order. Historian of the Ku Klux Klan, Robert Goldberg argued the Klan of the 1920s was similar to other social movements that sought to confront “the real threats [of] ‘status deprivation,’ cultural change, and the ‘acids of modernity.’” Thus, the Klan provided an opportunity for members to “save a nation, a faith, and a way of life.” [42] This attracted people who feared political corruption and cultural changes – nearly exclusively white Protestants – and targeted the “traditional ‘outsiders’” Beaton argued, including Jews, Blacks, and Catholics.[43] Overall, though, the rise and fall of the KKK in Denver happened in a matter of a few years. The Colorado chapters enlisted 35,000 to 50,000 male members and reached their height of power in the winter of 1924 to 1925, meaning Klan politicians ruled the legislative session in 1925. Several bills in this session attempted to prohibit marriages and procreation of the “unfit,” encourage stronger prohibition enforcement, and repeal the civil rights law of public accommodations.[44] Not many of the Klan’s proposed bills passed and later in 1925, a mutiny divided both the Klansmen and Klanswomen from their former brothers and sisters, eventually leading to their loss of power.[45]

The Ku Klux Klan relegated the female Klanswomen to a separate auxiliary chapter, the Women of the KKK (WKKK). In Women of the Klan, historian Kathleen Blee explained the WKKK appealed to white Protestant women because it provided an acceptable setting for their racial privileges, public morality, and private need for control. To Klanswomen, sexual, racial, religious, and national enemies were moral dilemmas they had to redefine.[46] The Women’s KKK was the chapter Minnie Love joined on July 16, 1924, just months before the 1924 election.[47] Joining the WKKK brought Love additional support and helped her get reelected. She was also the Excellent Commander of the WKKK and a prominent leader in the Klan’s political efforts while they were at their zenith.

As the Ku Klux Klan gained members in the 1920s, Americanism was a priority for the the KKK.This patriotic defense of traditional morality, law and order, religion (Protestantism), and brotherhood was a direct response to widening sexual mores, an increase of immigrants, and “threats” to the white race. Overall, the KKK worked towards controlling social, political, religious, and medical spheres. Within medicine, the science of heredity and white supremacy – eugenics and other forms of scientific racism – dictated the Klan’s goals and efforts in public health. Eugenicists and Klansmen both believed nonwhite populations would supersede the white race. Texts like influential eugenicist Lothrop Stoddard’s The Rising Tide of Color Against White World-Supremacy spread this idea and the concept of a looming danger of race suicide.[48] Consequently, eugenicists and KKK members worked hand in hand to propagate forcible sterilization of unfit populations, medically controlling their reproductive capabilities.

Love and other Klan members sought to exact control over Colorado’s cultural and medical spheres according to their moral, eugenic, and American doctrine. While in political office, Minnie Love, with the support of the Klan, would take this belief in medical control of reproduction to the legislature. Love’s proposal for legal sterilization in 1925 titled “A bill for an Act to prevent procreation of idiots, epileptics, imbeciles and insane persons” highlights her devotion to sterilization as procreative control that was “necessary for the immediate preservation of public peace, health, and safety.”[49] Her proposal also inspired other state legislators. Love received a letter from both R. E. Harrington of Nebraska and C. L. Funk of Utah requesting copies of her bill. Her response, housed in her archival collection, replied:

I think it will be better to begin with these unfortunates and perhaps later get a more comprehensive bill…I hope you may be able to pass such a law in your State as the question of the increase of all degenerates is getting to be a vital one.[50]

This 1925 attempt stalled in the House but was only second in a list of four proposed bills from 1913 through 1929 to legalize eugenic sterilization. Similarly, in an unpublished article, Love offered sterilization as a solution to “controlling sex functioning among the feeble minded and variously degenerate and unfit” rather than birth control. “Sterilization legally done is our only safeguard…it holds out to posterity its brightest hope of race regeneration,” she argued.[51] Despite Love’s support of sterilization since 1903, her 1925 introduction of a sterilization bill reveals how her eugenic values flourished under the KKK.

Love’s other introduced bills continued to deal with public health. In addition to bills related to funding and maintenance of state institutions, Love revealed her eugenic and social hygienist ideology with H.B. 33 for marriage licenses, H.B 34 and 35 regarding children in institutions, and H.B 489 to create the Division of Maternity, Child Hygiene, and Public Health Nursing.[52] Furthermore, some of Love’s other proposed bills in her two terms also included evidence of positive eugenics. For example, H.B. 36 from 1925 created the Child Welfare Bureau “to secure wiser and better trained parenthood thru the dissemination of knowledge pertaining to the natal and prenatal care and social hygiene of children.”[53] It is clear throughout Love’s political career that Klan and eugenic values colored her idea of public health.

The last social movement that sought to medically control reproduction to emerge in the twentieth century was birth control. Access to birth control at the turn of the century relied on diaphragms, spermicides, sponges, and condoms. Historian Donna Drucker credits an 1882 clinic in Amsterdam as the start of the modern contraceptive era that Margaret Sanger would lead in the United States.[54] Sanger, who would become a legendary figure of the birth control movement and women’s history, popularized birth control – first as a phrase for family limitation – and secondly as a method of controlling one’s sexuality. Before Sanger could spread the word, she came head to head with the Comstock Act in 1914. This act prohibited the manufacture, sale, and distribution of obscene goods, including information on contraceptives and sex. In Colorado, the Comstock Laws criminalized the publication, instruction, and sharing of where individuals could find contraceptive information.[55] Sanger’s use of the postal service in disseminating The Woman Rebel violated these governing rules and she fled to England but returned in 1916.[56] She continued to face difficulty in spreading information or contraceptive products but persisted in her mission.

Though scholars have debated Sanger’s support of eugenics, her writings in The Birth Control Review and books speak for themselves. “The eugenic and civilizational value of birth control is becoming apparent to the enlightened and the intelligent…birth control is not merely of eugenic value, but is practically identical in ideal,” Sanger wrote in “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda.” She echoed ideas of race suicide, promoted sterilization, race betterment, and “the true interests of eugenics” – shifting the “unbalance between the birth rate of the ‘unfit’ and the ‘fit,’ admittedly, the greatest menace to civilization.”[57] Angela Franks’ landmark revelations in Margaret Sanger’s Eugenic Legacy, pointed out that the “ideology of control” applied to birth control, population control, and eugenics. While Sanger believed birth control was the solution to reproductive management of those with “inheritable disease,” syphilis, and the feebleminded, she consistently supported and advocated for forced sterilization.[58] Sanger’s unwavering support of sterilization and advocacy of birth control to shape reproduction was a clear eugenic-based system of medical reproductive control.

An opposite image of Margaret Sanger, Minnie Love staunchly supported sterilization as opposed to birth control as the way to medically control reproduction. In the unpublished article, “Birth Control: Morally, Economically, Racially,” she called birth control advocates “fanatics” spreading propaganda without scientific backing.[59] To disprove and refute birth control advocates’ reasoning, Love questioned, “will it not encourage sexual excesses which spread venereal disease?” This rhetorical question reflected her social hygienist thoughts on sexuality and venereal disease. “Probably everyone agrees,” she admitted, “if they have given any thought to the increasing social complexities that beset us that among the derelicts of the population some method of birth control should be adopted legally,” not “a negative go-as-you please policy but a definite constructive plan.”[60] All in all, Love’s rebuttal of birth control access and education stemmed from her belief that there was “a better and less unmoral cure to our troubles.” Instead, the solution: “invoke science and the law to prevent the marriage of the unfit, segregation and surgical control of mental defects, epileptics, insane, and other such degenerates as are a menace to our civilization.”[61]

Love likely drafted this article on birth control around the time she was in her second term as a Colorado representative and her proposal of H.B. 369 on birth control. The 1925 session, full of Klan politics and eugenic efforts also included a bill proposal entitled “A bill for an Act to regulate the manufacture, sale and distribution of contraceptives and providing a penalty for the violation of this Act.” While many scholars in the past have cited this proposed bill as evidence that Love was a birth control supporter – using words like “advocate” or “encourage” rather than “regulate” – Antonovich has pointed out that, in conjunction with Love’s article, “regulate” should be interpreted in the negative.[62] Rather than a positive encouragement of birth control access, this bill, if it had passed, would likely have added to Colorado’s Comstock Laws. [63] With the ample evidence from Love’s written works, it is clear that Love was staunchly against the access and education of contraception that Margaret Sanger sponsored.

Conclusion

At the turn of the twentieth century, societal changes wreaked havoc on Victorian morality and mores. Changes in gender divisions of labor, acceptable sexual behavior, the increasing number of immigrants, and the expansion of medical knowledge led to four important social movements: social hygiene, eugenics, the Ku Klux Klan, and birth control. In response to the changes that plagued traditional moralists, these movements formed and grew across the United States. Moreover, the ideologies of each group infected the other whether through uncontrolled sex leading to venereal disease and thus insanity (a prerequisite for sterilization) or the Klan’s medical policing of procreation in the name of social hygiene and eugenics. While each movement centered on slightly different public objectives, they had the same private goal: the betterment and protection of the (white) race. In order to accomplish this underlying goal, each movement found ways to medically and politically control the reproduction of the “unfit,” namely the feebleminded, disabled, poor, or nonwhite.

These four social movements spread across the United States, affecting social, political, and medical spheres in many cities. In Denver, Colorado, one early female physician interacted with all four of the movements. While largely unstudied as a person of biographical merit, Dr. Minnie C. T. Love holds the key to understanding the way social hygiene, eugenics, the KKK, and birth control knowingly and unknowingly collaborated for the same end goal. Love, a proponent of eugenics, especially the sterilization of moral degenerates, was also actively involved in social hygiene ideology and treatment of venereal disease as well as the Ku Klux Klan. After her second term as a Colorado Representative, Love would also serve on the Denver School Board and publish fiction short stories before her death in 1942.[64] Love’s complex history reminds scholars to understand historical characters’ nuances; Love was an important and early woman in medicine and politics, despite her politics and values being counter to what is acceptable today. Nevertheless, Love’s eugenic underpinnings are clear. Confident in the solution to moral degeneracy, she continually advocated for forcible sterilization in the medical and political setting. Meanwhile, Love firmly denied the birth control movement any merit. Her pursuit of bettering the white race, regardless, shows us how social movements in the early twentieth century played off each other and created a racist, ableist, classist philosophy that politically and medically controlled reproduction.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Archival Collections:

Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934. MSS.1233. History Colorado, Denver, Colorado.

Colorado House and Senate Journals. William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder.

Minnie Love Collection 1930. MSS.2378. History Colorado, Denver, Colorado.

Senter Family Papers. MSS WH988, Box 37. Western History and Genealogy. Denver Public Library.

Newspapers:

“Marriage Exam Bill is Signed by Governor.” Longmont Times-Call, April 10, 1939.

“Minnie C. T. Love, Early-Day Doctor, Dies in Denver.” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1942.

“Women of Clubdom,” Rocky Mountain News, April 26, 1896.

Other:

Currey, D. V. “Social Hygiene in Relation to Public Health.” The Public Health Journal 15, no. 10 (October 1924): 460-467.

Dock, Lavinia L. Hygiene and Morality: A Manual for Nurses and Others, Giving an Outline of the Medical, Social, and Legal Aspects of the Venereal Diseases. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910.

Hooker, Donald R. “Social Hygiene and Social Progress.” Journal of Social Hygiene 10 (January 1924): 20-25.

Sanger, Margaret. “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda.” Birth Control Review 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 5.

Secondary Sources

Amesse, J. W. History of the Children’s Hospital of Denver-Colorado: A History of Achievement and Progress from 1910 to 1947. Denver: The Children’s Hospital Association, 1947.

Anton, Mike. “Colorado’s Dark Secret State Mental Hospital Sterilized Patients for More than 30 Years.” Rocky Mountain News, November 21, 1999.

Antonovich, Jacqueline. “White Coats, White Hoods: The Medical Politics of the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s America.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 96, no. 4 (winter 2021): 437-463.

Beaton, Gail. Colorado Women: A History. Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2012.

Blee, Kathleen. Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992.

Brandt, Allan. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Bruinius, Harry. Better for All the World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America’s Quest for Racial Purity. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

Dennett, Mary Ware. Birth Control Laws. New York: Frederick H. Hitchcock, 1926.

Drucker, Donna J. Contraception: A Concise History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020.

Fenwick, Robert W. “The ‘miracle’ of Children’s Hospital.” Empire Magazine, September 12, 1965.

Franks, Angela. Margaret Sanger’s Eugenic Legacy: The Control of Female Fertility. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2005.

Goldberg, Robert Alan. Hooded Empire: The Klux Klan in Colorado. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981.

Goldstein, Phil. In the Shadow of the Klan: When the KKK Ruled Denver, 1920-1926. Denver: New Social Publication, 2006.

Hansen, Randall and Desmond King. Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth Century North America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Jensen, Kimberly. “The ‘Open Way of Opportunity’: Colorado Women Physicians and World War I.” Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 3 (Autumn 1996): 327-348.

Kaufman, Martin. “The Admission of Women to Nineteenth Century Medical Societies.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 50, no. 2 (Summer 1976): 251-260.

Kline, Wendy. Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Love, Minnie C. T. “History of Women Practitioners in Colorado.” Colorado Medical Journal 8, no. 4 (April 1902): 147-150.

Luker, Kristin. “Sex, Social Hygiene, and the State; The Double-Edged Sword of Social Reform.” Theory and Society 27, no. 5 (October 1998): 601-634.

Whitmore, Michala. “State Industrial School for Girls.” Colorado Encyclopedia. Last modified November 01, 2022.

-

“Report of Three Years’ Public Health Work of the Denver Venereal Disease Clinic, Women’s Division,” FF150, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. The State Legislature created the Division of Venereal Diseases, under the State Board of Health, in 1919. The Legislature also created the State Detention Home in 1919, which opened its doors in 1920. ↑

-

Eugenic ideology centered on protecting, improving, and proliferating the right groups in the human race. While eugenicists explain their doctrine and actions as a way of improving the human race, they inexplicably meant the “fit” race of white, middle and upper class, educated, and non-disabled subcategory. I utilize the term “the race” throughout the paper because that is what contemporaries used. When social hygienists, eugenicists, the Klan, and birth control advocates say they desired to protect “the race” they meant the white “fit” groups. Additionally, demeaning language regarding mentally ill, intellectually and physically disabled peoples is widespread in sources from this time period. My use of this language is in reference to what physicians, politicians, and the public used at the time. ↑

-

Robert Alan Goldberg, Hooded Empire: The Klux Klan in Colorado (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981); Phil Goldstein, In the Shadow of the Klan: When the KKK Ruled Denver, 1920-1926 (Denver: New Social Publication, 2006). ↑

-

Goldberg, Hooded Empire; Gail Beaton, Colorado Women: A History (Boulder: University of Colorado Press, 2012). Traditional historiography begun by Robert Goldberg’s study on the KKK and repeated by women’s historian Gail Beaton in Colorado Women saw Love’s birth control bill as “advocating” for birth control access despite the language of the bill “to regulate.” ↑

-

Jacqueline Antonovich, “White Coats, White Hoods: The Medical Politics of the Ku Klux Klan in 1920s America,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 96, no. 4 (winter 2021): 437-463. ↑

-

For social hygiene and venereal disease research see Allan Brandt, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). For general overviews of eugenic history see Wendy Kline, Building a Better Race: Gender, Sexuality, and Eugenics from the Turn of the Century to the Baby Boom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001); Randall Hansen and Desmond King, Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth Century North America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013). ↑

-

For more on racialized eugenics see Alexandra Minna Stern, Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015); Jane Lawrence, “The Indian Health Service and the Sterilization of Native American Women,” American Indian Quarterly 24, no. 4 (summer 2000): 400-419; Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003). Basing their goal of improving the human race off of Charles Darwin’s radical theory on natural selection and the resulting social version – Social Darwinism – Eugenicists sought to control the reproduction of the unfit and encourage the reproduction of fit families. Additionally, Eugenicists, as they grew in influence, expanded their unfit targets from feebleminded, insane, and epileptic to poor, immigrant, and people of color (specifically Black, Mexican, and later in the century Native). ↑

-

The connection between the birth control movement and eugenics is a well-studied global phenomenon, especially compared to the other movements. See Jane Carey, “The Racial Imperatives of Sex: Birth Control and Eugenics in Britain, the United States and Australia in the interwar years,” Women’s History Review 21, no. 5 (2012): 733-752; Susanne Klausen, “The Race Welfare Society: Eugenics and Birth Control in Johannesburg, 1930-40,” in Science and Society in Southern Africa, ed. Saul Dubow (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 2017); Richard Sonn, “’Your Boy is Yours: Anarchism, Birth Control, and Eugenics in Interwar France,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 14, no. 4 (Oct. 2005): 415-432; Laura Briggs, Reproducing Empire: Race, Sex, Science, and U.S. Imperialism in Puerto Rico (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). ↑

-

“Minnie C. T. Love Biography,” FF1, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. Sources differ on whether Minnie Love was born in 1855 or 1856. Together, Charles and Minnie had three children: Tracy Robinson Love (who would grow up to become a doctor), Charles Waldo Love, and Nelson Roosevelt Love. According to the archival biography, the Love family moved to Denver in 1892, though other sources state they moved in 1893 or 1894. Minnie Love first appeared in Colorado newspapers in 1893. Scholars believe the Love family moved to Denver for Charles’ tuberculosis, which he would succumb to in 1907. ↑

-

Beaton, Colorado Women, 163. ↑

-

Minnie C. T. Love, “History of Women Practitioners in Colorado,” Colorado Medical Journal 8, no. 4 (April 1902): 147-150. ↑

-

Kimberly Jensen, “The ‘Open Way of Opportunity’: Colorado Women Physicians and World War I,” Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 3 (Autumn 1996): 330, 340. Women physicians made up 3.1% of physicians in the central US and 3.5% in the eastern US. ↑

-

Martin Kaufman, “The Admission of Women to Nineteenth Century Medical Societies,” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 50, no. 2 (Summer 1976): 251-260; Jensen, “The ‘Open Way of Opportunity’,” 327-348. Most medical societies accepted women by the 1880s according to Kaufman. This acceptance was not universal nor was it an easy way into the medical boy’s club. Historian Kimberly Jensen argues that even a picture of a more accepting society was not equivalent to actual acceptance. ↑

-

“Electricity in Diseases of Women,” FF154, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado; “The Lying-In Chamber,” FF153, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado; “Puerperal Infection,” FF152, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. The Lying-In Chamber is childbirth. In this speech/article, Love argued for women physicians to have more authority in maternal health and childbirth. Puerperal refers to what is now known as postpartum. ↑

-

“Biography,” Love Collection, History Colorado; “Woman in Clubdom,” Rocky Mountain News, April 26, 1896. Within the Women’s Club, there were numerous departments with different focuses (for example: reform vs. arts and literature). ↑

-

“City Improvement Society Leaflet,” FF158, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. The City Improvement Society, a branch of the Women’s Club reform department, claimed “the work is as great as human life.” ↑

-

The Rocky Mountain News documented many Women’s Clubs meetings, conventions, and changes. Love was an active member especially during the late 1890s and early 1900s. While she worked extremely hard within the Woman’s Club, other social organizations, and at her job with the Florence Crittenton Home, little is known about her home life nor that of her children and motherhood. ↑

-

“Minnie C. T. Love, Early-Day Doctor, Dies in Denver,” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1942; Minnie Love Collection 1930, MSS.2378, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado; Michala Whitmore, “State Industrial School for Girls,” Colorado Encyclopedia, last modified November 01, 2022. ↑

-

“Denver Chronicles the Growth of The Children’s Hospital,” Rocky Mountain News, April 28, 1985; Robert W. Fenwick, “The ‘miracle’ of Children’s Hospital,” Empire Magazine, September 12, 1965; J. W. Amesse, History of the Children’s Hospital of Denver-Colorado: A History of Achievement and Progress from 1910 to 1947 (Denver: The Children’s Hospital Association, 1947). Sometimes called the New Babies Hospital, the Babies Summer Hospital operated as an important healthcare access point for children of lower-class families. Moreover, the founders nearly named it the Blanche Roosevelt Children’s Hospital for Love’s sister, though they did not choose the name due to silver miners’ dislike of Roosevelt. In 1906, a group of women (philanthropic and medical) created the Children’s Hospital Association and began raising funds for a permanent structure. In 1908, Minnie Love, Hattie C. Colburn, Martha H. Terry, and Ectra R. Beard signed the articles of incorporation. ↑

-

Kristin Luker, “Sex, Social Hygiene, and the State; The Double-Edged Sword of Social Reform,” Theory and Society 27, no. 5 (October 1998): 601. ↑

-

D V Currey, “Social Hygiene in Relation to Public Health,” The Public Health Journal 15, no. 10 (October 1924): 460-467. ↑

-

Brandt, No Magic Bullet, 8, 14. ↑

-

Division of Venereal Disease, FF149, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

Brandt, No Magic Bullet, 31. ↑

-

“House Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Twenty-third Session. Convened at the City of Denver, Wednesday, January 5, 1921,” Colorado House and Senate Journals, William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder; “House Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Twenty-fifth Session. Convened at the City of Denver, Wednesday, January 7, 1925,” Colorado House and Senate Journals, William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder. Love proposed H.B. 9 to create a state hospital and training school for women, H.B. 33 to prevent the spread of venereal disease, and H.B. 299 for a venereal disease department within the State Board of Health in 1921. ↑

-

For more on IQ, eugenics, and race see Alexandra Minna Stern, “STERILIZED in the Name of Public Health: Race, Immigration, and Reproductive Control in Modern California,” American Journal of Public Health, 95, no. 7 (2005): 1128–1138; Ashely Montagu, ed. Race and IQ (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). Intelligence testing grew in importance throughout this time. Because IQ tests were in English or included pictures and questions based on middle-class life, anyone who spoke another language or did not conform to nor understand middle-class experiences could have a low IQ, often placing them at risk of going to state hospitals. ↑

-

“Criminal Abortion,” FF155, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

Indiana was the first state to legalize eugenic sterilization in 1907. Several states followed and at the federal level, the Supreme Court Case, Buck v. Bell (1927) wherein Judge Oliver Wendell Holmes infamously said “three generations of imbeciles is enough” supported the state laws. ↑

-

“House Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Nineteenth Session: Convened at the City of Denver, Wednesday, January 1, 1913,” Colorado House and Senate Journals, William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder; House Journal, 1925; “House Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Twenty-Sixth Session: Convened at the City of Denver, Wednesday, January 5, 1927,” Colorado House and Senate Journals, William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder; “House Journal of the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: Twenty-Seventh Session: Convened at the City of Denver, Wednesday, January 2, 1929,” Colorado House and Senate Journals, William A. Wise Law Library, University of Colorado Boulder. Colorado legislators attempted four times to legalize the practice. The first attempt began in 1913, followed by Love’s proposed bill in 1925, another effort in 1927, and lastly in 1929. The 1927 H.B. 509 was the closest eugenicists got as the bill passed both the House and Senate, but Governor Adams vetoed the bill. ↑

-

Because Colorado did not have legal backing for coercive sterilizations, many of the procedures went unrecorded. Lucile Schreiber’s story is one of the only documented cases of Colorado’s eugenic sterilizations because she went to court. ↑

-

Born in the mid-1920s, Lucile Schreiber began a pattern of running away and stealing. After kidnapping a baby, the Colorado Psychopathic Hospital diagnosed her with feeblemindedness (IQ of 89) and frequent masturbation – a precursor and/or symptom of vice and feeblemindedness. The Home of the Good Shepherd, a Catholic organization, took her in but sent her home due to violent outbursts. Her family, unable to manage her, sent her to the State Industrial School in 1938. There, physicians diagnosed her with an IQ of 99 and a “hysterical cough.” This brought her to the Colorado State Hospital, operated under the authority of Frank Zimmerman who actively promoted sterilization of patients. In 1942, Lucile underwent surgery where Dr. Schatz removed her appendix and fallopian tubes without consent. ↑

-

Harry Bruinius, Better for All the World: The Secret History of Forced Sterilization and America’s Quest for Racial Purity (New York: Vintage Books, 2007); Mike Anton, “Colorado’s Dark Secret State Mental Hospital Sterilized Patients for More than 30 Years,” Rocky Mountain News, November 21, 1999. Years later in 1954, Lucille visited Rep. Woodhouse, who was active in the state welfare system. With her help, Lucille was “restored to reason” with an I.Q. of 105 and sued the Colorado State Hospital. Though the court case proved the hospital had sterilized Lucille without legal authority, because Lucille had been sane for several years, the statute of limitations had run out. This case also brought to light hospital policy of sterilizing patients and Dr. Zimmerman’s support of eugenic sterilization bills throughout the 1920s. ↑

-

Eugenic values were prevalent throughout the twentieth century. While traditional histories of eugenics believed the Eugenics Movement disappeared after World War II because of the connection and similarity to Nazism, recent scholars have shown that eugenics ideology transformed into more acceptable forms of controlling populations they saw as unfit. For more on late-stage eugenics see Rebecca Kluchin, Fit to be Tied: Sterilization and Reproductive Rights in America, 1950-1980 (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2011); Molly Ladd-Taylor, Fixing the Poor: Eugenic Sterilization and Child Welfare in the Twentieth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017). ↑

-

Donald R. Hooker, “Social Hygiene and Social Progress,” Journal of Social Hygiene 10 (January 1924): 22. ↑

-

Lavinia L. Dock, Hygiene and Morality: A Manual for Nurses and Others, Giving an Outline of the Medical, Social, and Legal Aspects of the Venereal Diseases (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1910): 132, 136. ↑

-

Hooker, “Social Hygiene and Social Progress,” 23. ↑

-

“Marriage Exam Bill is Signed by Governor,” Longmont Times-Call, April 10, 1939. ↑

-

“Certificate of Election,” FF139, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

“House Journal,” 1921. Throughout Love’s career, she participated in numerous state organizations and furthermore, the state had an institution for nearly every social evil. The Colorado State Industrial School for Girls opened in 1895 and Love worked with the Board of Charities and Corrections on the treatment of girls there. The State Detention Home For Women with Venereal Disease opened in 1920 and te State Board of Health appointed Love to help operate the facility. In 1921, Love proposed a bill to establish a State Reformatory and Training School for Girls, specifically for women with venereal disease and/or drug habits, but it did not come to fruition. In 1925, she would again propose the establishment of a State Reformatory and Industrial Training School for Female Persons. Importantly, H.B. 33 on venereal disease spread did pass the House. ↑

-

Antonovich, “White Coats, White Hoods,” 439. ↑

-

Antonovich, “White Coats, White Hoods,” 439-440. ↑

-

Goldberg, Hooded Empire, xiii, 165. ↑

-

Beaton, Colorado Women, 183. The KKK added Catholicism to the target list due to the rise in Catholic immigrants. ↑

-

Goldberg, Hooded Empire, 89. ↑

-

For more information on the KKK of the 1920s see Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, and the American Political Tradition (New York: Liveright, 2018); Kelly J. Baker, Gospel According to the Klan: The KKK’s Appeal to Protestant America, 1915-1930, repr. ed. (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2017). For more information on Colorado and Denver’s KKK see Goldberg, Hooded Empire and Goldstein, In the Shadow of the Klan. ↑

-

Kathleen Blee, Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992). ↑

-

Membership Card, Senter Family Papers (MSS WH988), Box 37, Western History and Genealogy, Denver Public Library. ↑

-

Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1920). The concept of race suicide, spread by alarmist eugenicists, was the belief that the white birth rate was declining, and nonwhite birth rates were outpacing them. The stereotype that nonwhite populations were more fertile (or hyper-fertile) furthered this fear. ↑

-

“H.B. 60, sterilization,” FF169, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

“Correspondence related to legislation,” FF176, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

“Birth Control,” FF151, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado, 8-10. I examine this article in depth on page 25-26. ↑

-

House Journal, 1925. H.B. 489 was a contentious bill within the KKK as it divided members who were for or against licensure of nurses. For more on the nurse bill see Goldberg, Hooded Empire. ↑

-

“Bill No. 36, Child Welfare,” FF168, Charles and Minnie Love Collection 1887-1934, MSS.1233, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado. ↑

-

Donna J. Drucker, Contraception: A Concise History (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2020). ↑

-

Mary Ware Dennett, Birth Control Laws (New York: Frederick H. Hitchcock, 1926). Dennett was one of the founders of the National Birth Control League. The Comstock Act, a federal law, inspired states to create their own laws. Referred together as “Comstock Laws,” these laws were not always within the same bill. For more information on the Comstock Act see Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, “Victoria Woodhull, Anthony Comstock, and Conflict over Sex in the United States in the 1870s,” The Journal of American History 87, no. 2 (Sept. 2000): 403-434. ↑

-

Angela Franks, Margaret Sanger’s Eugenic Legacy: The Control of Female Fertility (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2005). Abroad, Sanger met and collaborated with neo-Malthusians like Havelock Ellis, a sexologist and eugenicist, who would influence her ideas on birth control and eugenics. ↑

-

Margaret Sanger, “The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda,” Birth Control Review 5, no. 10 (October 1921): 5. Women’s historians, traditionally, idolized Sanger as the creator of the US birth control movement and thus the feminist ability to control one’s own sexuality and reproduction. Eugenics historians too have ignored Sanger’s eugenic connections. However, recently scholars have begun to discuss the way birth control enacted eugenic ideologies and worked together to control procreative abilities of the “unfit” for race betterment. Sanger explicitly supported negative eugenic actions of sterilization and contraception for unfit groups but dismissed positive eugenics as an impactful methodology. ↑

-

Franks, Margaret Sanger’s Eugenic Legacy, 8, 188. ↑

-

“Birth Control,” Love Collection, History Colorado, 8. Historian Jacqueline Antonovich claims in a “White Hoods, White Coats” footnote that Love submitted “Birth Control” for publication in the Journal of Social Hygiene in 1926. While I have not found anything to refute this possibility, I have also not found anything to verify it. Rather, I believe this article was potentially part of a larger thesis or book as she referenced a “previous chapter.” Additionally, Love used collective language, particularly at the end of the article, stating “we would invoke science and law” and “our program…would be constructive and based upon high moral ideals of conduct.” Perhaps Love participated in a eugenics (or similar) organization like some scholars have suggested (Antonovich and a few other scholars state, without citing evidence, that Love was a founding member of the Denver chapter of the National Eugenics Society with Mary Elizabeth Bates). Antonovich further claims that Love submitted this article in 1926 to the Journal of Social Hygiene. I concur that Love likely drafted this article around her second time in office and near the time she proposed H.B. 60 on sterilization. Love referenced the 1920 census in her discussion of population and Malthusian population control. Moreover, when discussing one of the Malthusian “checks” on population, she mentioned “the world war” that had recently ended. Even further, Margaret Sanger coined the phrase “birth control” in 1914. Additionally, the article, located in folder 151 has handwritten notes, repeated sections and rewrites, making it an in-progress article from Love. The pages, because of the rewrites and other edits, appeared out of order textually. While there are handwritten numbers that look to be of the same handwriting as the edits (i.e., belonging to Love), I reorganized the paper to the best of my ability in order to understand Love’s argument. I have used the page numbers as handwritten for ease of reference. ↑

-

“Birth Control,” 8. It is important to remember, at this time “birth control” or contraceptives was single-use forms of preventing conception such as diaphragms, spermicides, and condoms or even herbal remedies. Research, production, and advocacy for the birth control pill would not begin for several decades. ↑

-

“Birth Control,” Love Collection, History Colorado, 10, 12. ↑

-

Antonovich, “White Coats, White Hoods,” 455, fn 67. ↑

-

Emphasis added. This bill, proposed in 1925, has caused a debate amongst historians. Up until 2021, scholars like Goldberg and Beaton have cited this bill as evidence of Love’s support of birth control, many of which did not cite the unpublished article, “Birth Control: Morally, Economically, Racially.” Historian Jacqueline Antonovich is the first scholar to challenge these interpretations using the title of the bill and the article from Love’s History Colorado Collection. Unfortunately, the title of the bill is the only evidence of the bill. Upon examination at the Colorado State Archives, the bill housed there is missing the actual text of the bill. The archivist and I were unable to find any other reference to the text of the bill. The Senate postponed House Bill 369 indefinitely. ↑

-

Minnie Love Collection 1930, MSS.2378, History Colorado, Denver, Colorado; “Minnie C. T. Love, Early-Day Doctor, Dies in Denver,” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1942. Love would serve on the School Board in 1925 and publish fiction short stories in 1930. ↑