“Change will occur, for whose benefit?”: Gentrification in Five Points, 1975 – 1984

By: Michelle Rich

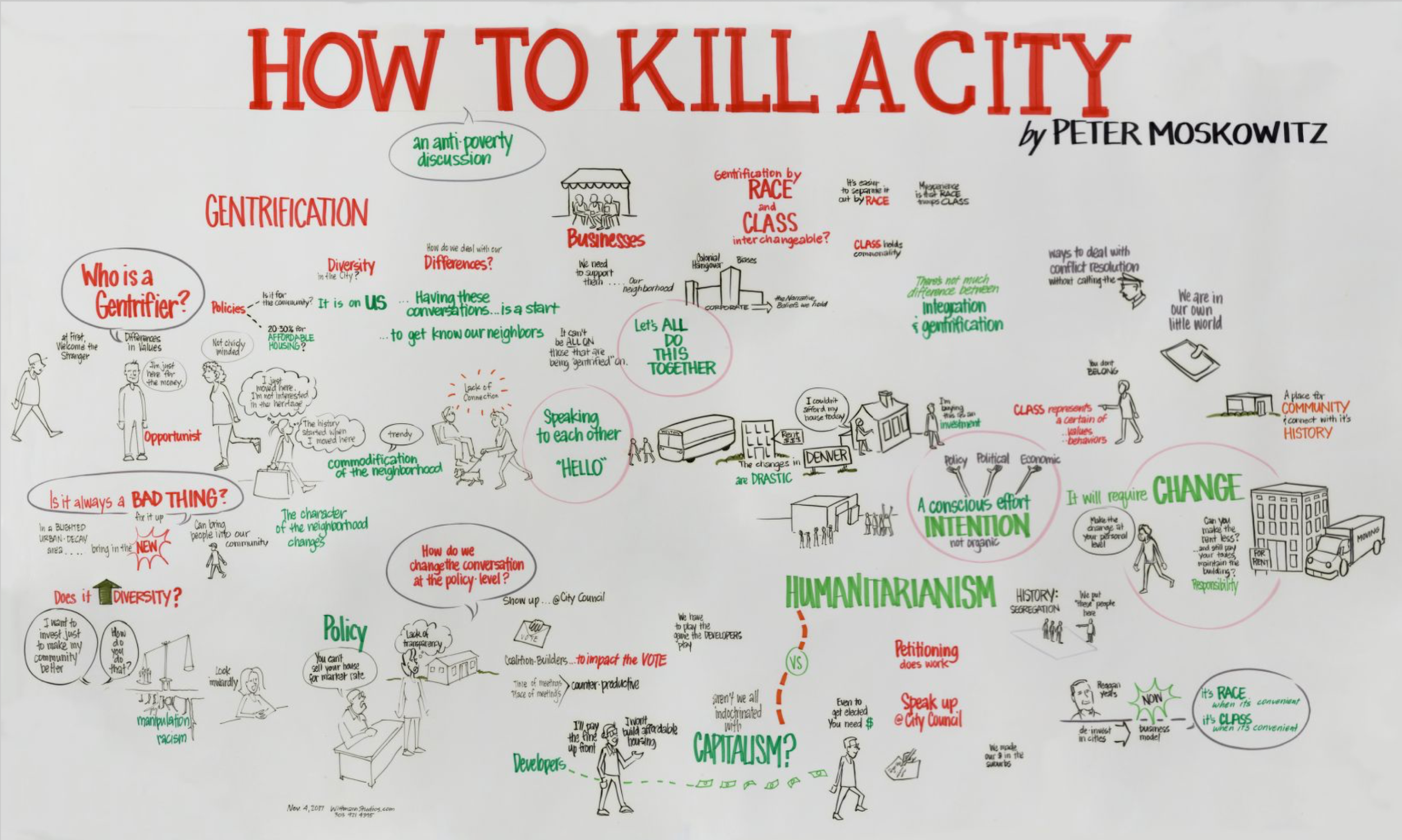

On November 4, 2017, residents of Denver, presumably some from Five Points, met to discuss P.E. Moskowitz’s book, How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood, at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library located in the heart of Denver’s historic Five Points neighborhood.[1] According to the Denver Public Library, the book discussion was sponsored by R.A.D.A, an organization that “provides a safe and responsible space to discuss community issues and movements of the day with respect and compassion within a structured environment.”[2] This platform provided local residents the opportunity to address the the sensitive issue of gentrification and its impact in Denver, particularly the Five Points neighborhood. While the concerns of the residents present at this community meeting were legitimate, it is important to acknowledge that gentrification had been occurring well before 2017. Residents in the early 1980s were also discussing similar issues as the residents that evening at the Blair-Calwell library.

Observers noted signs of gentrification in the Five Points neighborhood as early as 1984. Significant indicators related to housing influenced the change in demographics of the Welton Street corridor in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood between the late-1960s through the 1980s. The changes occurring during this twenty-year period were visible to long-time residents of Five Points. Decreased access to housing and the increased need for financial housing assistance led to the displacement of low-income Black residents from Five Points and contributed to the early stages of the gentrification of the neighborhood. Subsequently, the result of unchecked gentrification ultimately led to the loss of the cultural memory of Five Points. Therefore, the intentional preservation of the neighborhood’s Black history and culture through the protection of historical buildings significant to Black Denver and the establishment of Black cultural celebrations is essential to curb the negative impact of gentrification.

Scholarship related to gentrification began in the 1960s by British sociologist Ruth Glass when she coined the term in her 1964 study London: Aspects of Change. In her Marxist analysis of neighborhoods in London, Glass argues, “once this process of ‘gentrification’ starts in a district, it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working class occupiers are displaced, and the whole social character of the district is changed.”[3] This includes increased housing prices and new businesses aimed at serving the upper classes. Professor emeritus at MIT Phillip Clay’s focus on urban housing policy and community-based organizational development contributed to the study of gentrification in the 1970s by developing the four stages of gentrification.[4] The four stages are summarized as:

The first phase involves “pioneering” gentrifiers who move into a neighborhood in search of cheaper rent. Their presence encourages the second stage of gentrification—a wave of middle-class gentrifiers. In the third stage, corporate actors, such as real estate companies and chain retail stores, enter into the neighborhood seeking to profit from both groups of gentrifiers. This stage is also marked by the displacement of long-time residents. In the fourth and final stage, the neighborhood becomes so saturated by private developers, corporations, and the wealthy, that even the original pioneers can no longer afford to live there.[5]

Geographer Neil Smith author of The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City (1996) continues the discussion of gentrification. In his preface, he quotes excerpts of Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis by drawing parallels between the pioneers of nineteenth-century American West and the “new urban frontier” of the twentieth century. Similarly, Clay uses language such as “pioneer” in his first stage of gentrification in order to conjure up the imagery of the frontier and western expansion. Smith contends, “the term ‘urban pioneer’ is therefore as arrogant as the original notion of ‘pioneers’ in that it suggests a city not yet socially inhabited; like Native Americans, the urban working class is seen as less than social.”[6] The “’discourse of decline’ dominated the treatment of the city” and contributed to the view that cities were the new wilderness.[7] According to Smith, “the frontier discourse serves to rationalize and legitimate a process of conquest, whether in the eighteenth-and nineteenth-century West, or in the late-twentieth-century inner city.”[8]

In their 2017 book, How to Kill a City, P.E. Moskowitz challenges the idea of “gentrification as a product of cultural and consumer choice.”[9] Rather, Moskowitz argues that gentrification is a product of systemic racism that has impacted the access to housing for people of color, which has resulted in less wealth and capital than their white counterparts.[10] In addition, they suggest that neoliberalism—the emphasis on economic growth rather than the needs of citizens—is to blame for the burgeoning gentrification in cities.[11] In conversation with Phillip Clay’s stages of gentrification, Moskowitz also suggests that there is a precursory stage “in which a municipality opens itself up to gentrification through zoning, tax breaks, and branding power. This preparatory phase is rarely seen or talked about because it happens so long before most people witness gentrification in action.”[12]

While Denver is very much part of the frontier myth and continues in some cases to perpetuate the narrative of western expansion, much of what is written on the Five Points neighborhood during the late-nineteenth century and early-twentieth century emphasizes Denver’s jazz era and its connection to the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: The New Negro’s Western Experience edited by Cary D. Wintz and Bruce Glasrud is a collection of essays devoted to the expansion of scholarship on the Harlem Renaissance into regions outside of Harlem, specifically the American West. Editors Wintz and Glasrud argue, “the Harlem Renaissance, or the New Negro literary and artistic movement, was a truly national phenomenon and must be understood as such. This volume represents another step in that direction by focusing its attention on the Harlem Renaissance in the West.”[13] In this same edition, George H. Junne Jr., professor of Africana Studies at the University of Northern Colorado, contributes to the discussion of Denver’s relationship to the Harlem Renaissance with his emphasis on Five Points as an emerging Black cultural center.[14] Furthermore, Moya Hansen, an independent historian whose focus is on Denver’s Black population and the Five Points, argues that “between 1920-1950 Denver’s black population established a thriving community in the Five Points area.”[15] Hansen explains that Five Points had reached its “heyday” as a jazz center by 1950, further emphasizing the neighborhood’s historical connection to jazz.[16]

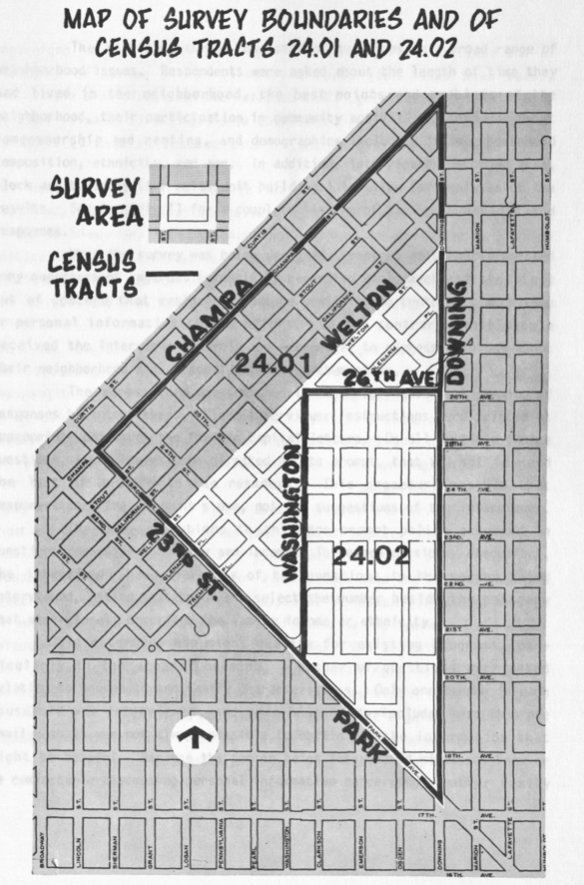

Discussions of gentrification in Denver have been limited to neighborhoods in north Denver and the River North Arts District—sometimes considered part of the greater Five Points neighborhood—which situates the discussion of gentrification between the 1990s and 2000s. Recent graduate of University of Colorado at Denver’s School of Public Affairs Doug Holland completed his master’s capstone project on the Globeville and Elyria-Swansea neighborhoods. His project, titled “A Study of Gentrification and Displacement in North Denver Neighborhoods,” argues that various planned public projects will ripen the area for gentrification and therefore displace many of the neighborhood’s residents.[17] Similarly, Laura Conway’s honors thesis, “Gentrification In The Neoliberal World Order: A Study of Urban Change in the River North District of Denver, Colorado,” defended at the University of Colorado at Boulder in the Department of Geography, analyzes the rapid change in the River North Arts District (RiNo) in the early 2000s. She argues, “Rino’s rapid transformation is a paradigmatic example of neoliberal place making.”[18] Considering both studies were completed at local universities, one of the limitations of examining the historiography of Denver is the lack of scholarship outside of Colorado that focuses solely on its neighborhoods.

This essay will make use of previous scholarship on gentrification, particularly Moskowitz’s ideas on the inclusion of systemic racism and its impact on housing as a tool to analyze the initial stages of gentrification in Five Points. Additionally, this essay will contribute to the growing scholarship on Denver’s more recent history of its neighborhoods. Essential to this essay’s analysis are two local reports, the Five Points Neighborhood Plan 1975 and the 1984 Five Points Area Residents’ Survey. Along with these reports I use a variety of the newspaper clippings from several collections from members of the Denver community that are housed at the Denver Public Library. The main publications for these clippings are The Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post.

The primary geographical focus of the essay is concentrated around the Welton Street corridor in order to establish a clear connection to the Five Points Residents’ Survey conducted in 1984. However, it is important to note that the exclusion of the River North Arts District (RiNo) from this analysis was a deliberate choice made due to the scope and limitations of this paper. While RiNo is a prime example of gentrification occurring in Denver, the primary focus of this essay is the Welton Street corridor and its historical importance to the Five Points community.

The lens of analysis I employ is based on the framework of gentrification used by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which aligns with Moskowitz’s How to Kill a City. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, “Many anti-displacement activists define gentrification as a profit-driven, race, and class change of a historically disinvested neighborhood. Race is tied to class and power in gentrification.”[19] The National Low Income Housing Coalition argues:

“The development process should enable community members to identify the types of housing, services and infrastructure that should exist in their neighborhood. The process should value longtime residents’ visions of neighborhood change and give the power of decision-making to community residents. A healthy community is one that acknowledges and supports the importance of racial equity, community, and culture.”[20]

Many of the themes of the suggestions and conclusions of the 1984 Residents’ Survey are reflected in the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s framework, and therefore, its use will provide a renewed analysis of early gentrification in Five Points.

Early History of the Five Points Neighborhood

Migration of African Americans into Colorado began as early as the late-1850s. The first known Black settlers were James Beckwourth, “Aunt” Clara Brown, and Barney Lancelot Ford. As a co-founder of Pueblo, Colorado, Beckwourth was a famous fur trapper and trader.[21] Freed from enslavement in 1859, “Aunt” Clara Brown migrated to Denver and eventually settled in Central City, Colorado.[22] Barney Lancelot Ford came during the gold rush after escaping on the underground railroad, and he is most known for opposing Colorado statehood until African Americans were given their right to vote. [23] After the Civil War, African Americans continued to migrate into Colorado as an extension of the Exoduster migration.[24] By 1890 the “U.S. Census reported that about 6,000 African Americans lived in Colorado, with about 5,000 owning property. Of those 6,000, 3,254 lived in Denver.”[25]

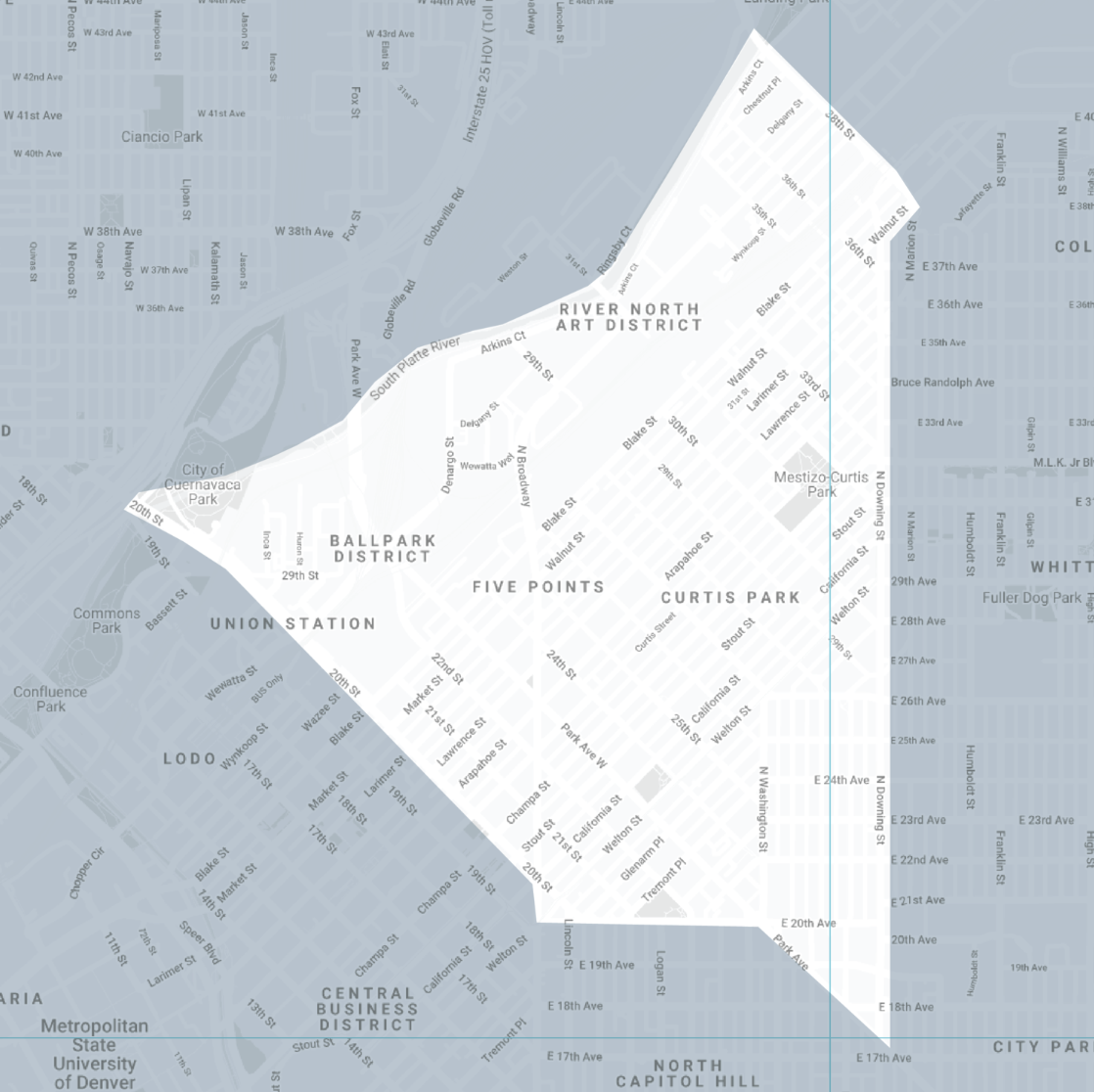

The Five Points neighborhood originated along several streetcar lines northeast of downtown and appealed to various people of color due to its proximity to downtown and the railyards where many were employed. According to the online Colorado Encyclopedia, Five Points got its name in 1881, “when the streetcar signs could not fit all the street names for the line’s terminus.”[26] Hansen describes the boundaries of Five Points as “the neighborhood, a roughly triangular area north and east of downtown Denver, is bounded on the west by Twentieth Street, on the north by the South Platte River and Thirty-eighth Street, on the east by Downing Street and on the south by Park Avenue and East Twentieth Avenue.”[27]

Figure 1. Map of the boundaries of the Five Points neighborhood in Denver Colorado. Sub-neighborhoods of Five Points include: Ballpark, Curtis Park, Whittier, Cole and River North Arts District[28]

In 1900, historians Thomas J. Noel and Nicholas J. Wharton wrote, “Five Points was primarily an African American neighborhood, with Welton Street representing Black Denver’s ‘main street’.”[29] Five Points continued to be a Black cultural center through the 1950s. According to the Denver Public Library’s neighborhood history of Five Points, “the period was also the height of the neighborhood’s reign as a cultural and entertainment destination, with local nightspots host to jazz and blues musicians of the day.”[30] The Rossonian Hotel and Lounge is considered to be one of the most prominent buildings in Five Points and was home to a popular jazz club. During the early twentieth century the Rossonian accommodated many Black musicians, many of whom were turned away by white-owned hotels downtown. The Colorado Encyclopedia highlights, “the list of musicians who stayed at the hotel and performed at the lounge is long and distinguished; it includes Duke Ellington (who once spent a whole summer there), Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Billie Holiday, and Ella Fitzgerald.”[31] By the 1960s the hotel and lounge began to decline as a result of anti-discrimination legislation, which contributed to the Black population moving out of Five Points.

By the 1960s many Black residents in Five Points began to move east towards Park Hill. According to Hanson, “Denver’s Fair Housing Act (1957) and the Civil Rights movement enabled middle and upper-class Black residents to leave the Five Points area. The aging neighborhood entered a decline that earmarked it as an area of urban blight, belaying the optimism of black residents four decades earlier.”[32] The Denver Public Library’s website on the Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History states, “In 1959, the population of Five Points was 32,000; by 1974, it had declined to 8,700. “[33]

Housing as an Indicator of Gentrification and the Changing Population in Five Points

Five Points’ proximity to the central business district, and its access to a variety of goods, services, and employment has long been favored as one of the neighborhood’s best attributes which has attracted new residents.[34] The 1974 Five Points Neighborhood Plan was created in conjunction with the 1972 Community Renewal Program which addressed revitalization efforts for the city of Denver. Policy recommendations in the 1974 Five Points Neighborhood Plan, written by John A. Harris of the Neighborhood Planning Section and approved by the Denver Planning Board, were created to encourage residents of all income levels to benefit from a new and desirable Five Points. City planners were encouraged to make Five Points a “mixed income, high density residential” neighborhood.[35]

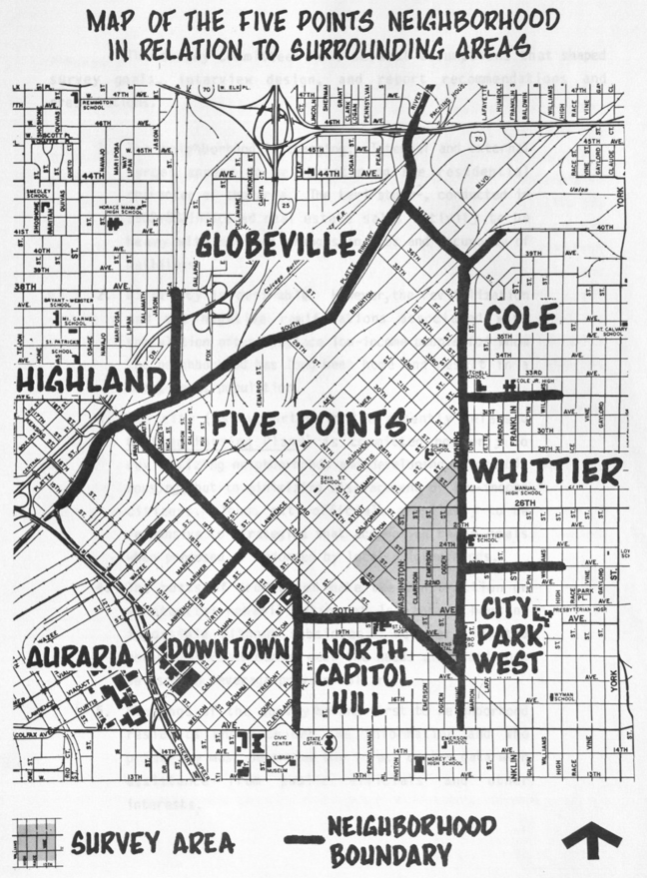

While the 1974 plan encouraged redevelopment to benefit all residents, the 1984 Residents’ Survey cautioned, “the neighborhood is changing. Internal and external forces appear to be threatening residential character of the area.”[36] The Five Points Area Residents’ Survey was conducted in December 1984 by Hope Communities, Inc., and the Concerned Citizens Congress of Northeast Denver (CCC). Hope Communities, Inc. was a non-profit organization providing access to affordable housing for residents in northeast Denver, and the CCC provides advocacy for the concerns of northeast Denver residents. According to the Residents’ Survey, the CCC—one of the contributing organizations to the survey—addressed issues of displacement and encouraged involvement of the community in public processes.[37] The residents interviewed for this survey lived in a portion of Five Points immediately east of the Welton street corridor bordered by Welton, Downing, and 23rd (present day Park Avenue) Streets, making their input vital to the changes occurring around the Welton Street corridor.

Figure 2. Maps of the boundaries of the residents surveyed in the 1984 Five Points Survey. Original maps published in the report.[38]

![]()

The survey lists the following as their main goals: “(1) develop an updated community profile; (2) collect information about community needs with an emphasis on housing; (3) inform residents about existing programs and services; and (4) examine how the neighborhood’s residential character is being threatened by external or internal forces.”[39] Overall, this survey was a tool to preserve the neighborhood for the already existing residents, despite their income level.

As previously mentioned, the population in Five Points had significantly decreased by 1974. Along with the dwindling population, access to housing also had diminished; the number of housing units accessible to renters dramatically decreased between 1950 and 1984. A 1971 Denver Post article reported that approximately 100 homes had been condemned by city officials. The same article claimed one census tract in Five Points saw a decline of the number of housing units of 43 percent, and in many cases homes were not being rebuilt on the vacant land.[40] Similar statistics on the decrease of housing units were reported in the 1974 Five Points Neighborhood Plan. According to the plan, “in 1950 there were 7,090 units and by 1974 the number had been reduced to 4,357, or a 39% loss.”[41] The deterioration and demolition of buildings within Five Points led to a decrease in livable units. Reverend Jon Marr Stark, religious leader and activist in Five Points, during a 1971 interview proclaimed, “we are becoming the parking lot for the downtown Denver business community and several offices [between the central business district and Five Points].”[42] The 1984 Residents’ Survey identified a continued trend of loss of units with their conclusions stating, “a large number of units have been lost over the last decade and a half through conversion and demolition.”[43] While the deteriorating buildings warranted demolition, the absence of a plan to rebuild forced long-term residents to be displaced.

Another contributing factor that led to the decaying housing stock was the establishment of fair housing policies. Former city planner, John A. Harris recalled that the culture of Five Points began to fade once the city adopted fair housing policies in the 1950s, which led to an exodus of wealthier Five Points residents to move east towards Park Hill. As a result, a number of vacant and deteriorating buildings were left behind, and renting became the primary means to acquiring housing.[44] Although many single-family homes were converted to multi-family units, the number of owner-occupied units decreased and renter occupancy increased, which according to the 1974 Five Points Neighborhood Plan caused the trend of deterioration and blight within the neighborhood. During his interview in 1980, longtime Denver resident and real estate agent Bennett Horton who worked primarily in Five Points recalled an increase in vacant units, corroborating the observations from Reverend Jon Marr Stark and 1984 Residents’ Survey.

The lack of financial support for home rehabilitation and subsidized housing contributed to gentrification in and around the Welton Street corridor. In order to rehabilitate the existing rundown homes in the neighborhood, the 1984 study suggested that there was a great need for government subsidies to help meet the needs of the residents due to the high construction costs. The study maintained, “limited government funds cannot meet the needs alone and must be used to leverage private dollars.”[45] As a result of the federal government eliminating its support for local housing assistance, Denver Mayor Federico Peña and his administration had to develop a plan to help meet the housing needs of Denver’s residents. Just fifteen years prior, in 1969, the Department of Housing and Urban Development committed $500,000 to fund a variety of community programs in a one-block section of Five Points.[46] However, reports of dilapidated units and poor living conditions surfaced in the media as early as 1971. According to Councilman Elvin R. Caldwell in a 1971 Rocky Mountain News article, “There is no question that quality of life is related to decent, clean and adequate housing.”[47] Caldwell’s comments came at a time when he was calling on the local municipality and federal government to support low-cost housing programs—part of the Model City Plan—to prevent the further decline of Five Points. Despite some financial assistance from the federal government in 1969, it had little impact on impending decline of the neighborhood.

In order to alleviate the financial burden of home restoration in Five Points, the 1984 Residents’ Survey offered potential solutions. In response to Mayor Peña’s Unified Housing Plan, the survey summarized their major findings. According to the survey, the Unified Housing Plan’s solutions aimed to “lower land costs and improve compatibility of uses through more appropriate zoning, reduce water taps and other fees for subsidized housing, complement rental rehab grants with Community Development funds, and utilize below-market Section 312 loans to rehabilitate rental buildings.”[48] Despite suggested solutions by the city’s administration, the 1984 Residents’ Survey concluded that the solutions presented would not be enough, particularly for the lower-income residents. Therefore, the survey suggested that:

Extraordinary measures will be needed to induce new construction or substantial rehabilitation. Unusual and immediate actions in forms or resident organizing and public policy changes need to be taken. The infusion of public and private dollars carefully leveraged to maximize their impact must be considered as steps to revitalize the neighborhood in ways that allow its diversity to remain.[49]

The 1984 Residents’ Survey clearly established the need to prioritize the cooperation between public and private entities to provide economic support with the emphasis on maintaining the neighborhood’s existing cultural diversity and preventing gentrification.

Specific recommendations for the city by the organizations that conducted the 1984 Residents’ Survey included promoting the development of low-income housing in exchange for new construction permits for downtown, increasing access to the home improvement programs, and support for mortgage assistance programs.[50] At the same time, the organizations that put together the Five Points Residents’ Survey were extremely concerned about the neighborhood’s character and cautioned against the negative consequences of gentrification. In their section “Observations for the Future” the survey made clear, “Change will occur, but in what form? For whose benefit? The preservation of the residential character of the survey area makes sense from several perspectives. As costs for new construction and development continue to rise, the wisdom of demolishing old neighborhoods rather than maintain[ing] them must be questioned.”[51] As a means to reduce the negative impact of gentrification in the neighborhood at this time, the survey suggested outside private sector capital should generate involvement in jobs programs, promote lending and investment, encourage mixed-income housing opportunities, and most importantly, better understand the values and concerns of the Five Points community.[52] Community voice in the decision making process was strongly encouraged by the Residents’ Survey; however, there is little evidence to suggest developers and city officials paid attention to the survey’s findings.

Lower than average housing prices and rents, compared to other Denver neighborhoods, led to changing demographics in Five Points that contributed to the early stages of gentrification. The 1984 Residents’ Survey reported, “both rents and home sales prices are far below citywide averages,” which in turn caused a lack of capital to be poured into rehabilitation.[53] According to the Residents’ Survey, there “appears to be little incentive for owners or developers to build or maintain housing.”[54] Therefore, low prices attributed to the dilapidation of the current stock of housing units within Five Points. However, on the flipside, the same survey suggests that “some moderate-income Anglos are purchasing and renovating bargain-priced old home and forming ‘mingles’ households to meet the costs of this undertaking.”[55] This phenomenon brought forth early stages of gentrification that residents began to observe as early as 1980, four years before the Residents’ Survey was conducted. Some residents began to see housing prices increase, although they remained below other neighborhoods in Denver. Horton, in his 1980 interview, recalled the shock at the rising cost of homes in Five Points which resulted in a change in demographics in the neighborhood. Seemingly he was referring to the increase of white residents moving into the neighborhood.[56] In the same interview, interviewer Bernie Mitchell, who is presumably white, admitted that he could only afford a home in Five Points and that he was priced out in other “more-desirable” neighborhoods.[57] According to the 1984 Residents’ Survey, “the Levy Study, conducted in 1982-83, indicated real estate sales activity to be heavy with obvious changes in uses and occupancy.”[58] The survey also found that “gentrification…has preserved buildings but probably has decreased the number of housing units. Old homes previously divided to house multiple families are frequently re-converted to spacious single-family residences,” adding to the decreasing number of units available for existing residents and forcing the displacement of others. [59]

While the 1984 Residents’ Survey called for increasing housing subsidies, tensions over subsidized housing occurred in the late 70s and early-80s. Even prior to the findings in this survey, newspaper reports were already identifying the tension with new residents: Five Points had “more than 300 units of federally subsidized housing. That’s more subsidized housing than any other Denver neighborhood has, a fact that does not please the residents,” stated one article from the Rocky Mountain News dated from 1979.[60] The rhetoric found in this article was evocative of the changing attitudes of newer residents and suggests the increased economic status of these residents. Tensions rose so high that “more than 100 Curtis Park [sub-neighborhood of Five Points] residents recently filed suit in federal court against state and federal housing agencies to try and stop another subsidized housing development, which would cover three blocks.”[61] Five Points had been changing demographically by the late-1970s, and a significant indicator of this transition had been changes in access to and attitudes towards subsidized housing.

Racial and ethnic changes in population in Five Points began in the 1950s. According to the 1970 U.S. Census, the population of Five Points was approximately 13,000, with most residents identifying as Anglo. The Black population of Five Points had decreased from being the majority in the 1950s to approximately 39% in 1970. By the time of the 1974 Five Points Neighborhood Plan, the Denver Planning Office estimated a continued decline in residents residing in Five Points. Their estimates of the total population in Five Points at the time of the report was closer to 8,700.[62] The changes in racial demographics in Five Points had also been observed by two longtime residents: Erma Turner and Gertrude E. Moore. Erma Turner was interviewed in a 1979 Rocky Mountain News article, “people that moved out of the suburbs are buying and restoring the houses,” suggesting a growing wealthier white population into the neighborhood.[63] According to the same article, author Karen Newman stated that, “[Turner] approves of the new racial mix in Five Points,” which further suggests that a noticeable change in demographics—increasingly white—was occurring in Five Points.[64] In her 1980 interview with Bernie Mitchell, Moore acknowledged several “whites” moving in and welcomed them, attributing the neighborhood’s turnaround to their presence.[65] While both women welcomed the new racial dynamics of the neighborhood, others were more cautious. Councilman Caldwell was fearful that the increase of more affluent residents into Five Points would push the older and poorer residents out, and that there would be nowhere for them to go, resulting in a continued displacement of long-term residents.[66] The 1984 Resident Survey concluded, “Anglos are moving into the neighborhood at a faster rate than any other group,” acknowledging a change in the racial demographics of Five Points.[67] Throughout the 1970s and into the 1980s, Five Points had seen a consistent trend of white residents moving into the neighborhood.

Although some Denver residents acknowledged the positive impact of the initial revitalization of Five Points, others were concerned about the visible gentrification as a result. In an article titled “Five Points Comeback,” written in 1979, the author describes Five Points thriving after a period of decline. However, City Councilman Elvin Caldwell—once again—warned, “some poor, elderly residents could be displaced, and have no place to go.” The article continued, “our hope is that the city officials will keep a close eye on this neighborhood, encourage development, but also take whatever steps are necessary to assure that the prosperity of some doesn’t make life worse for others.”[68] While Caldwell was encouraging continued development in the area, he advocated for the neighborhood’s long-term residents and to prevent further displacement. One example that Caldwell was weary of was of a University of Colorado Professor, who was rehabilitating a Curtis Park home. The homeowner stated that he was “annoyed at charges that his kind is driving up prices and forcing older residents out.”[69] He was angry that, “’Displacement’ is being thrown in our face with a regularity that is getting a little tiresome.”[70] Although this resident may have been focused on the positive impact he felt he had brought to the neighborhood after a period of decline, he was clearly blind to the unintended consequences that his participation in gentrification had on the erasure of the neighborhood’s culture.

Conclusion: Preservation of Black History as a Means to Resist Gentrification

The 1984 Residents’ Survey emphasized that one of the goals of the planning team for the Welton-Downing Triangle area for the Five Points Plan Update was “work toward a desirable mix of people of varying income levels, ages and ethnic backgrounds.”[71] The survey acknowledged that this goal was in step with the history of Five Points, and in order for this diversity to be preserved it must be done so by an intentional and conscious effort.[72] Although gentrification started in Five Points during the late-1970s and early-1980s, the community action and the preservation of the neighborhood’s Black history were able to minimize its impact.

First, the preservation of historic buildings including the Justina Ford home and the Rossonian Hotel and Lounge contributed to the limited gentrification in the Welton Street corridor compared to other parts of Denver. Both the Justina Ford House and the Rossonian Hotel and Lounge played an integral part in the history of Five Points. Their preservation as historic buildings have helped contribute to the memory of the neighborhood’s Black history. In 1984, an application was completed to the National Register of Historic Places to nominate the Justina Ford House for preservation. According to the application, the house had been moved from 2335 Arapahoe to its current location at 31st Street and California. Prior to its moving, the home was set to be demolished. However, community leaders encouraged the owners to salvage it and donate it to a non-profit organization.[73] The Justina Ford House would later become the home to the Black American West Museum located on the north-end of the Welton Street corridor. Colorado Preservation Office records from as early as 1981 reveal efforts to preserve the Rossonian. According to the application, “the Rossonian is one of the most significant buildings in the Welton Street area in its role in the black history of the commercial strip.”[74] The Rossonian is located on one of the corners of the intersection of the neighborhood’s namesake, and it is a visual reminder of the neighborhood’s rich history. The preservation of this building is an important step in sustaining the collective memory of Denver’s Black community.

Community events such as Five Point’s Juneteenth celebrations and annual jazz fest contribute to the preservation of the neighborhood’s history. In 1953 Otha P. Rice, owner of Rice’s Tap and Oven located at 28th and Welton, organized the city’s first Juneteenth celebration.[75] Today, the Juneteenth celebration is a weeklong affair centered in Five Points honoring Black culture and highlighting Denver’s Black history. In 2004, in an attempt to preserve the jazz legacy of Five Points, the city of Denver put on its first Five Points Jazz Festival. For the last twenty years the jazz festival has been located within the Welton Street corridor and has expanded since its inception. These community events have helped retain the neighborhood’s culture and diversity despite increased gentrification in recent years. According to P.E. Moskowitz, “gentrification suppresses and displaces memory.”[76] Without the intentional work to preserve the neighborhood’s Black history, gentrification will surely erase its memory.

Appendix

Figure 1. The drawing below was created by artist Kris Whitman during a community discussion on Peter Moskowitz’s book How to Kill a City at the Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library located in the Five Points neighborhood in northeast Denver.[77]

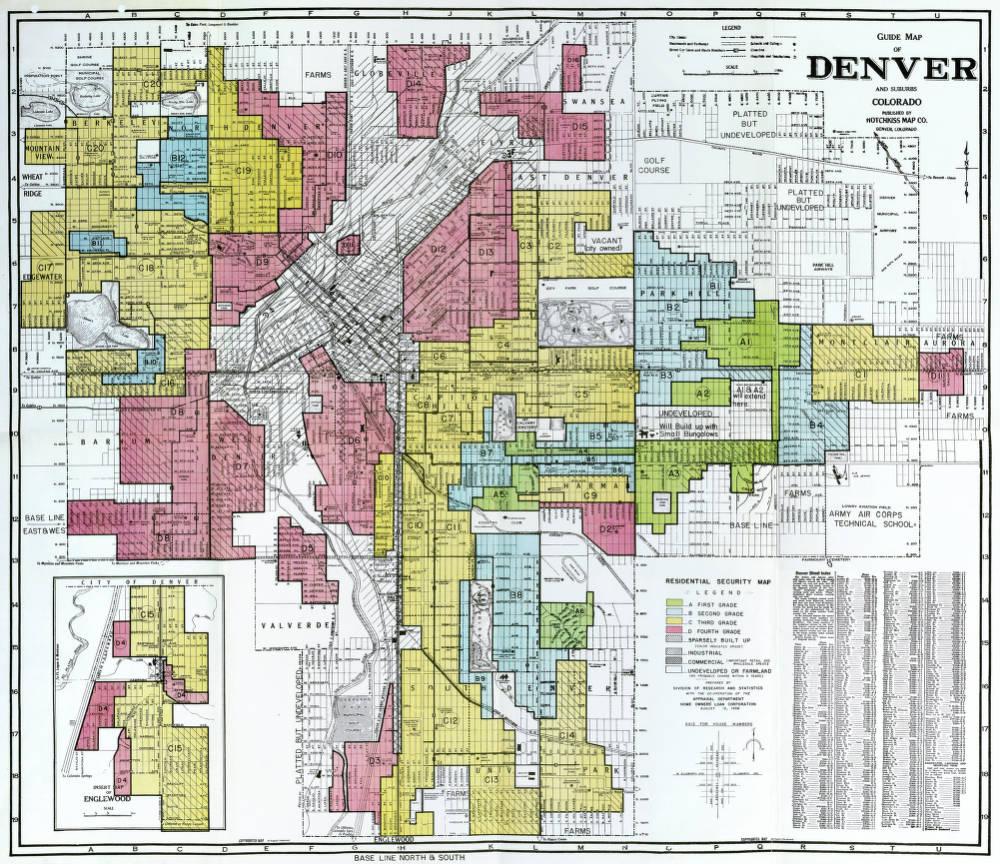

Figure 2. According to the Denver Public Library Digital Collections, “[this] map is dated August 15, 1938 and illustrates the redlining of neighborhoods in the City and County of Denver where minorities were excluded from receiving home loan funds because they were considered poor economic risks.”[78] According to this map, the Five Points neighborhood is mostly in the “fourth grade,” which is deemed most at risk.

Figure 3. Below is the proof sheet of photographs taken of the Rossonian Hotel and Lounge. The proof sheet was located in the Thomas Yates Papers collection at the Denver Public Library. Along with the proof sheet were other documents related to the historical preservation of the building.[79] Since its designation as a historic building, developers have been interested in redeveloping this space, however, to this day it sits vacant. Despites its vacancy, the Rossonian is still a reminder of Denver’s Black history.

Bibliography

Primary

“Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library.” Accessed March 12, 2023. https://www.facebook.com/BlairCaldwell.dpl.

Colorado Cultural Resource Survey – Preservation Office. Inventory Record The Rossonian. Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation.

Denver Planning Office. “Five Points Neighborhood Plan – Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections,” 1974. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll1/id/858/rec/39.

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey – Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections,” 1984. Denver Public Library Special Collections. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll1/id/521/rec/1.

“Five Points comeback,” May 19, 1979. Denver Public Library collection number WH2129 box number 187.

“Five Points rebounding as vital neighborhood.” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1979.

Horton, Bennett. interview by Bernie Mitchell. 1980. in Denver. cassette tape. Denver Public Library Collection C MSS OH143-2.

Jones, Cecil. “Caldwell urges action on housing snags.” Rocky Mountain News. August 10, 1971.

Moore, Gertrude. Interview by Bernie Mitchell. 1980. in Denver. cassette tape. Denver Public Library Collection C MSS OH143-1.

National Register of Historic Place Inventory. Justina Ford House Site Number 5DV1493. Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation.

Newman, Karen. “Five Points – new life in old neighborhood.” Rocky Mountain News. May 13, 1979.

Pearce, Ken. “Housing Loss Taking Five Points Downhill.” Denver Post. December 31, 1971.

Post Washington Bureau. “$500,000 Tabbed For Five Points.” Rocky Mountain News. August, 5 1969.

R.A.D.A. How to Kill a City – Photographs – Western History – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections. 2017. 1 poster : color, hand-drawn, 48 x 83 in. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/95458/rec/2.

“Residential Security Map.” 1938. Denver Public Library. call number CG4314.D4 E73 1938 .U556. accessed March 16, 2023. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p16079coll39/id/902.

“Rossonian Proof Sheet.” Thomas Yates Papers. Denver Public Library. call number ARL327 box 1. accessed March 16, 2023.

Schiller, Tom. “Five Points rehabilitation project to be spotlighted.” Rocky Mountain News. September 19, 1983.

Verrengia, Joseph B. “Denver breathing life back into historic Rossonian.” Rocky Mountain News. November, 22, 1992.

Secondary

“African American History in the American West Timeline.” Black Past. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history-west-timeline/.

Colorado Encyclopedia. “Rossonian Hotel.” Text, March 16, 2016. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/rossonian-hotel.

Conway, Laura. “Gentrification in The Neoliberal World Order: A Study of Urban Change in the River North District of Denver, Colorado.” (Undergraduate Honors Thesis, University of Colorado, 2015).

Denver Public Library History. “Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History,” June 16, 2014. https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history.

Denver Public Library. “Justina Ford: Denver’s First Female & Black-American Physician.” Accessed May 7, 2023. https://www.denverlibrary.org/blog/research/dcochran/justina-ford-denvers-first-female-blackamerican-physician.

DUSP MIT. “Phillip Clay.” Accessed April 18, 2023. https://dusp.mit.edu/people/phillip-clay.

Dwell Denver. “7 Reasons to Love Five Points Neighborhood • Dwell Denver Real Estate.” Accessed March 16, 2023. https://www.dwell-denver.com/blog/five-points-neighborhood.

“Encyclopedia of the Great Plains | EXODUSTERS.” Accessed May 3, 2023. http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.afam.018.

“Five Points,” Colorado Encyclopedia. Accessed March 5, 2023. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/five-points.

Glasrud, Bruce A., and Cary D. Wintz, eds. The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: The New Negro’s Western Experience. New Directions in American History. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Glass, Ruth. London: Aspects of Change. ed. by the Centre of Urban Studies. London: MacGibbon & Kee. 1964. xviii-xix.

Hansen, Moya. “Pebbles on the Shore: Economic Opportunity in Denver’s Five Points Neighborhood, 1920-1950.” Colorado History. no. 5 (2001). 96.

Hermon, George Jr. “Community Development and the Politics of Deracialization: The Case of Denver, Colorado, 1991-2003.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594 (2004): 143–57.

Holland, Douglas C. “A Study of Gentrification and Displacement in North Denver Neighborhoods.” (Master’s Capstone Project, University of Colorado at Denver, 2016). 3-5. http://dougholland.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Gentrification-Capstone-Paper-Final.pdf.

Junne Jr., George H. “Harlem Renaissance in Denver.” From The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: The New Negro’s Western Experience, ed. Bruce A. Glasrud and Cary D. Wintz. New York: Routledge, 2012. 2.

Leonard, Stephen J., and Thomas J. Noel. A Short History of Denver. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2016. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/cudenver/detail.action?docID=4648535.

Marr, Garry. “’Mingles’ moving housing markets.” Financial Post. November, 19, 2011. https://financialpost.com/personal-finance/mingles-moving-housing-markets.

Moskowitz, Peter. How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood. New York, NY: Nation Books, 2017.

Moore, Rashad. Review of Review of How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood, by P. Moskowitz. Journal of African American Studies 22, no. 2/3 (2018): 286.

“Moya Hansen.” Black Past. accessed February 12, 2023. https://www.blackpast.org/author/hansenmoya/.

National Low Income Housing Coalition. “Gentrification and Neighborhood Revitalization: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?” Accessed March 1, 2023. https://nlihc.org/resource/gentrification-and-neighborhood-revitalization-whats-difference.

Noel, Thomas J., Nicholas J. Wharton, and John Hickenlooper. “Northeast Denver.” In Denver Landmarks and Historic Districts, 97–110. University Press of Colorado, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cd0mft.10.

Pirolo, Monica. “Elvin R. Caldwell.” Text, May 2, 2017. https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/elvin-r-caldwell.

Pohorelsky, Jana. “Gentrification Without Displacement? A Cautionary Tale from Brooklyn to Detroit – Kennedy School Review,” July 22, 2019. https://ksr.hkspublications.org/2019/07/22/gentrification-without-displacement-a-cautionary-tale-from-brooklyn-to-detroit/.

“R.A.D.A. Social Justice Book Discussion.” Accessed March 20, 2023. https://www.denverlibrary.org/event/rada-social-justice-book-discussion.

Smith, Neil. The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City. Taylor and Francis Group, 1996. https://www-taylorfrancis-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/books/mono/10.4324/9780203975640/new-urban-frontier-neil-smith.

Stephens, Ronald Jemal, La Wanna M. Larson. Images of America: African Americans of Denver. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008.

-

“Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library,” accessed March 12, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/BlairCaldwell.dpl. ↑

-

“R.A.D.A. Social Justice Book Discussion,” accessed March 20, 2023, https://www.denverlibrary.org/event/rada-social-justice-book-discussion. ↑

-

Ruth Glass, London: Aspects of Change, ed. by the Centre of Urban Studies (London: MacGibbon & Kee, 1964), xviii-xix. ↑

-

“Phillip Clay,” DUSP MIT, accessed April 18, 2023, https://dusp.mit.edu/people/phillip-clay. ↑

-

Jana Pohorelsky, “Gentrification Without Displacement? A Cautionary Tale from Brooklyn to Detroit – Kennedy School Review,” July 22, 2019, https://ksr.hkspublications.org/2019/07/22/gentrification-without-displacement-a-cautionary-tale-from-brooklyn-to-detroit/. ↑

-

Neil Smith, The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City, (Taylor and Francis, 1996), accessed April 18, 2023, https://www-taylorfrancis-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/books/mono/10.4324/9780203975640/new-urban-frontier-neil-smith, xvi. ↑

-

The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City, xv. ↑

-

The New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City, xvi. ↑

-

Peter Moskowitz, How to Kill a City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood (New York, NY: Nation Books, 2017), 9. ↑

-

How to Kill a City, 5. ↑

-

How to Kill a City, 5. ↑

-

How to Kill a City, 6. ↑

-

Bruce A. Glasrud and Cary D. Wintz, eds., The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: The New Negro’s Western Experience, New Directions in American History (New York: Routledge, 2012), 2. ↑

-

George H. Junne Jr., “Harlem Renaissance in Denver,” From The Harlem Renaissance in the American West: The New Negro’s Western Experience, ed. Bruce A. Glasrud and Cary D. Wintz, New York: Routledge, 2012), 2. ↑

-

Moya Hansen, “Pebbles on the Shore: Economic Opportunity in Denver’s Five Points Neighborhood, 1920-1950,” Colorado History. no. 5 (2001), 96. “Moya Hansen,” Black Past, accessed February 12, 2023, https://www.blackpast.org/author/hansenmoya/. ↑

-

Hansen, “Pebble on the Shore,” 97. ↑

-

Douglas C Holland, “A Study of Gentrification and Displacement in North Denver Neighborhoods,” (Master’s Thesis, University of Colorado at Denver, 2016), 3-5. http://dougholland.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Gentrification-Capstone-Paper-Final.pdf ↑

-

Laura Conway, “Gentrification in The Neoliberal World Order: A Study of Urban Change in the River North District of Denver, Colorado,” (Undergraduate Honors Thesis, University of Colorado, 2015). ↑

-

“Gentrification and Neighborhood Revitalization: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, accessed March 1, 2023, https://nlihc.org/resource/gentrification-and-neighborhood-revitalization-whats-difference. ↑

-

“Gentrification and Neighborhood Revitalization.” ↑

-

“African American History in the American West Timeline,” Black Past, accessed March 21, 2023, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history-west-timeline/. Ronald Stephens, La Wanna M. Larson, Images of America: African Americans of Denver (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008), 12. ↑

-

“African Americans of Denver,”12. ↑

-

“African Americans of Denver,” 13. ↑

-

According to the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains and the University of Nebraska, Exodusters referred to the “tens of thousands of African Americans moved into the Great Plains to begin new lives during the last three decades of the nineteenth century. These Plains settlers have often been referred to as Exodusters. Beginning in the 1870s and continuing into the 1890s, the Exodusters settled in all Great Plains states and territories, even as far north as Canada, but Kansas and what would become Oklahoma Territory were the main destinations.” “Encyclopedia of the Great Plains | EXODUSTERS,” accessed May 3, 2023, http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.afam.018. ↑

-

Ronald Jemal Stephens, La Wanna M. Larson, and Colo) Black American West Museum and Heritage Center (Denver, African Americans of Denver, Images of America (Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008), http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/fy1002/2007940250.html. ↑

-

“Five Points | Articles | Colorado Encyclopedia,” accessed March 5, 2023, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/five-points. ↑

-

Hansen, “Pebble on the Shore,” 99. ↑

-

“7 Reasons to Love Five Points Neighborhood • Dwell Denver Real Estate,” Dwell Denver, accessed March 16, 2023, https://www.dwell-denver.com/blog/five-points-neighborhood. ↑

-

Thomas J. Noel, Nicholas J. Wharton, and John Hickenlooper, “Northeast Denver,” in Denver Landmarks and Historic Districts (University Press of Colorado, 2016), 97–110, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1cd0mft.10, 99, 103. ↑

-

“Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History,” Denver Public Library History, June 16, 2014, https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history. ↑

-

Colorado Encyclopedia, “Rossonian Hotel,” Text, March 16, 2016, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/rossonian-hotel. ↑

-

Hansen, “Pebble on the Shore,” 97. ↑

-

“Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History.” ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey – Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections,” 1984, Denver Public Library Special Collections, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll1/id/521/rec/1, ix. Bennett Horton, interview by Bernie Mitchell, 1980, in Denver, cassette tape, Denver Public Library Collection C MSS OH143-2. ↑

-

Denver Planning Office. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” vii. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey – Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections,” 1984, Denver Public Library Special Collections, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll1/id/521/rec/1, 78. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” vi and 1a. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” v. ↑

-

Ken Pearce, “Housing Loss Taking Five Points Downhill,” Denver Post, December 31, 1971. ↑

-

Denver Planning Office, 3. ↑

-

“Housing Loss Taking Five Points Downhill.” ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” x. ↑

-

Karen Newman, “Five Points – new life in old neighborhood,” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1979. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” vii. ↑

-

Post Washington Bureau, “$500,000 Tabbed For Five Points,” Rocky Mountain News, August, 5 1969. ↑

-

Cecil Jones, “Caldwell urges action on housing snags,” Rocky Mountain News, August 10, 1971. According to the online Colorado Encyclopedia, “Elvin R. Caldwell Sr. (1919–2004) was one of the most significant African American policymakers in Colorado history. An accountant and businessman, Caldwell joined many community organizations before beginning his political career in 1950 in the Colorado House of Representatives. He later served on the Denver City Council. In both positions Caldwell worked to eliminate the routine injustices suffered by Colorado’s African American community.” Monica Pirolo, “Elvin R. Caldwell,” Text, May 2, 2017, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/elvin-r-caldwell. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” 54. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xiii. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xvi. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xi. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xvii. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” x. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” 37. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” 38. The term “mingles” can refer to a group of singles who purchase a home together or cohabitate a home together. Garry Marr, “’Mingles’ moving housing market,” Financial Post, November 19, 2011, https://financialpost.com/personal-finance/mingles-moving-housing-markets ↑

-

Bennett Horton Oral History. ↑

-

Bennett Horton Oral History. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” vii. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” 42. ↑

-

“Five Points rebounding as vital neighborhood,” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1979. ↑

-

“Five Points rebounding as vital neighborhood.” ↑

-

Denver Planning Office, “Five Points Neighborhood Plan – Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections,” 1974, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll1/id/858/rec/39, 1-3. ↑

-

Karen Newman, “Five Points – new life in old neighborhood,” Rocky Mountain News, May 13, 1979. ↑

-

“Five Points – new life in old neighborhood” ↑

-

Gertrude Moore, Interview by Bernie Mitchell, 1980, in Denver, cassette tape, Denver Public Library Collection C MSS OH143-1. ↑

-

“Five Points – new life in old neighborhood” ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” viii. ↑

-

“Five Points comeback,” May 19, 1979. Denver Public Library Collection Number WH2129 Box Number 187. ↑

-

“Five Points rebounding as vital neighborhood.” ↑

-

“Five Points rebounding as vital neighborhood.” ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xii. ↑

-

“Five Points Area Residents’ Survey,” xii. ↑

-

National Register of Historic Place Inventory, Justina Ford House Site Number 5DV1493, Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation. Dr. Justina Ford was the first licensed Black-American female doctor in the U.S. Xvante F., “Justina Ford: Denver’s First Female & Black-American Physician,” Denver Public Library, Accessed April 23, 2023, https://www.denverlibrary.org/blog/research/dcochran/justina-ford-denvers-first-female-blackamerican-physician ↑

-

Colorado Cultural Resource Survey – Preservation Office, Inventory Record The Rossonian, Office of Archaeology & Historic Preservation. ↑

-

“Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History.” ↑

-

How to Kill a City, 210. ↑

-

R.A.D.A, How to Kill a City – Photographs – Western History – Denver Public Library Special Collections and Digital Archives Digital Collections, 2017, 1 poster : color, hand-drawn, 48 x 83 in, 2017,

https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll22/id/95458/rec/2. “Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library,” accessed March 12, 2023, https://www.facebook.com/BlairCaldwell.dpl. ↑

-

“Residential Security Map,” 1938, Denver Public Library, call number CG4314 .D4 E73 1938 .U556, accessed March 16, 2023, https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p16079coll39/id/902. ↑

-

“Rossonian Proof Sheet,” Thomas Yates Papers, Denver Public Library, call number ARL327 box 1, accessed March 16, 2023. ↑