A Collective Separation: Palestinian Communal Divides in Lebanon Between 1948-1967

By: Lucas Kiesel

In 1948, Amina Hasan Banat and her two daughters were forced to abandon Shaykh Gunnun, a town formerly found in the northern sector of modern-day Israel, after Israeli Defense Force (IDF) tanks and airplanes started targeting their home. Amina’s husband was a Palestinian soldier stationed near Shaykh Gunnun to protect the village’s inhabitants from invading Israeli forces, but when the IDF started bombing the town his unit was ordered to escape across Lebanon’s southern borders. “He left me and he went,” Amina remarked when recalling her escape. “The men had crossed and fled before the borders had closed. They had run away…I had two daughters-my husband could not even take one of them.”[1] Like many of Shaykh Gunnun’s inhabitants, Amina had been left behind and now faced the challenge of being the sole caretaker to guide her children safely into Lebanon.

Amina was fortunate enough to pass through several Druze regions, areas occupied by a sect of Muslims that believe in components from all Abrahamic faiths, and happened upon a traveling Druze caravan that was also heading towards Lebanon. Amina traded all her valuables and Palestinian liras for a donkey so her children could rest during the long journey. When Amina’s family made it into Lebanon, they were placed into a refugee camp close to the town of ‘Ayta al-Sha’b, located near the northeast border with Israel. Lebanese authorities moved Amina into a makeshift cabin with a nearby fig tree, a luxury not all refugees received when they arrived. After leaving her daughters behind to guard the tree from other refugees, Amina asked a local Lebanese man for clean water to help alleviate her fatigue. “He told me: ‘Shoo shoo, go out, leave, leave, leave,’ I told him, ‘Why, my brother, what did I do to you?’ He said, ‘You Palestinians we don’t welcome you. We don’t welcome you, you are unclean.’”[2] Even after escaping into Lebanon Amina’s family was threatened by other refugees and the native residents, all of whom offered little sympathy.

When the IDF pushed into the northern front of Galilee on October 23, 1948, hundreds of Palestinian volunteers abandoned their military posts and fled northward, seeking refuge in Lebanon. Thousands of Arab civilians living in northern Palestine were shocked to see their militia completely abandon them and soon many followed these soldiers into southern Lebanon to also escape from the IDF. Most civilians were women and children that had been separated from the men in their family, either because they died in combat or had already withdrawn into Lebanon. This widespread separation left many Palestinian mothers all alone with the arduous task of leading their remaining family members to safety, all while having little to no supplies to protect against the elements or potential Israeli attacks.[3] This instance of Palestinians being displaced into neighboring Arab States would be known as the Nakba, or Palestinian Catastrophe, and permanently changed Palestine’s social fabric.

David Eldan. Arab people fleeing from their Galilee villages as Israeli troops approach. October 30th, 1948.

The Nakba is still a prevalent event for academics researching Palestine and the cultural shift of Palestinians after their displacement. Countless viewpoints have tried to assess the Palestinian community following their dispersal and how they changed while living in different host countries. One outlook suggests that Palestinians created a paradoxical community out of their desire to maintain pre-war traditions while simultaneously incorporating new social systems to combat external threats. Historians that adopted this interpretation discovered a compelling number of changes that occurred because of Palestinians immediate reactions following the Nakba. This interpretation popularized the argument that a distinctive cultural identity formed around a common sense of suffering and a collective memory of Palestine that all displaced Palestinians held, regardless of their differences, yet this approach glossed over other contributing factors that existed outside their community space.[4] A crucial piece of insight is thus missing from the current historical lens. An equally in-depth consideration of the externalities that changed how Palestinians interacted with each other is necessary.

In response to these shortcomings, scholars moved their research focus onto the host countries to learn if their actions perpetuated cultural shifts within the Palestinian community. These new interpretations still included the foundational changes that occurred internally and independently of any outside influences during the Nakba but enhanced that historical information by connecting it to exterior forces. One strategy involved the examination of refugee camps in the context of Lebanon’s restrictive policies. This outlook framed Palestinian isolation as a direct consequence of their host country’s mismanagement, not a self-imposed restriction meant to preserve a pure Palestinian identity. Another method considered Lebanon’s religious demographic and their prejudice against Muslim Palestinians as the origin point that sewed divisions within the Palestinian community.[5] In comparison to historians’ original methodology, these approaches cast a wider net to better explain the root causes behind Palestinians communal tensions.

This paper will focus on the oral histories of Palestinians who were displaced to show that their living standards within Lebanon’s borderlands encouraged new communal divisions and worsened pre-existing tensions. As earlier historians have linked the Nakba to the formation of a collective memory that unified Palestinians under a new shared identity, this paper argues that the Palestinian community’s initial fracturing in 1948 was a precursor to their separation as refugees in Lebanon. I also contend that communal disconnections caused by prolonged Lebanese hostility and deteriorating living conditions started to paradoxically reconnect the Palestinian community by the 1950’s. This claim does not deny the formation of a collective memory, nor does it dispute the significance that idea played for Palestinian realignment. Rather, I affirm that Lebanon’s unwelcoming environment disrupted Palestinians communal coherence, their social relationships within the community, and fundamentally changed their cultural identity. Considering these divisions in the larger story of the Nakba will supply a comprehensive understanding of how Palestinians mutual suffering was both a force that disconnected and relinked their sense of community.

Generational Differences

Events leading into the Nakba wore the Palestinian community down to a fragile state that could easily be shattered on a moment’s notice. In September 1947, Britain announced that the Palestine Mandate, which had allowed British administrative control over the territories of Palestine and Transjordan since 1922, would end on May 15th, 1948. This decision came ahead of the United Nations General Assembly’s (UNGA) ongoing vote to create a separate Jewish and Arab state within the partitioned lands of Palestine. Approval for this partition plan hit an impasse with the Arab League and its member states, who acted on behalf of the Palestinians after Britain dismantled the Arab Higher Committee (AHC) and the Supreme Muslim Council in 1936. The league’s elites rejected every proposal offered by the UNGA in a bid to garner domestic support and assert their countries’ foreign independence. This caused the UNGA to put more pressure on Britain to help in creating and enforcing a partition plan. Britain instead abruptly proclaimed they were leaving the area, effectively hurling Palestine into turmoil while wiping their hands clean of any responsibility. A period of intercommunal conflict began as Jewish forces moved to secure territories that were promised to them by the most recent UNGA resolution.[6]

Britain’s announcement led to an increase in violence that paved the way for a refugee crisis in Palestine. Despite the Arab League assuring Palestinians that they were prepared to defend against any military aggression, Israeli soldiers displaced nearly 400,000 Arabs in the months between the mandate’s termination. Some resistance groups retaliated with their own attacks, stacking atrocities on top of atrocities, and creating a chaotic environment from which the Arab League saw an opportunity to exploit. On May 15th, 1948, the Arab-Israeli war began after the combined militaries of Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Transjordan, and Iraq invaded Israel to defend Palestine. In truth each country was only interested in claiming any captured territory or resources from themselves. The coalition was uncoordinated and unprepared to face a foe that was better equipped, trained, and had 10,000 more soldiers. This advantage allowed Israel to implement Plan D, a campaign that targeted potentially hostile Arab villages so soldiers could systematically expel Palestinians in areas allocated to the Jewish state. Plan D increased fears amongst Arab residents and caused their exodus from Palestine to be irreversible. By the war’s conclusion in March 1949 the IDF had expelled around 110,000 Palestinians into Lebanon and 700,000 in total, leaving only 160,000 native Arabs within the new borders of Israel.[7]

(Left) The UNGA proposal for the partition of Palestine, 1947. (Right) The Arab Israeli Armistice line, 1949.

Communal tensions between Palestinians existed prior to their displacement, but such conflicts had been defined by those willing and unwilling to resist their oppressors. Fifi Khouri, born in 1922 in the city of Yafa, recalled during an interview with Bushra Mughrabi about how members of the municipality of Yafa, including her father, often fought over how to respond to embargos placed over them by Britian in 1948. These disagreements forced the elders to make one of two choices, capitulate or resist. Khouri’s father was instructed by Arabs outside of Yafa to give in to the embargo, but when he presented this to the municipality, it sparked infighting. “There was a shaykh among the members…who put his gun on the table and said, ‘There is no way we are raising the white flag.’” After some time reflecting on this moment, Fifi revealed to the interviewer how uneasy Palestinians were amongst one another. “You have to know that each person called the other a traitor. So, who is the real traitor, it remains a mystery.”[8] This idea that any passive bystander was an accomplice to Palestine’s downfall returned to segregate different generations of Palestinians when they were displaced into Lebanon.

Lebanon’s fluctuating border policies escalated tensions between Palestinians of the old and new generation. During the first few months of war, Lebanon initially adhered to the Arab League’s open border policy and allowed fleeing Arabs to enter the country. This was done so Lebanon could “absorb babies, women and old people from among Palestine’s Arabs.” Unfortunately, the addition of escaping soldiers increased the number of refugees living in Lebanon to 20,000 by April 1948, which caused the AHC to release a proclamation that recommended all military aged men and women to help their fellow soldiers by returning to active duty. This did little to stop massive groups of Palestinians escaping into neighboring Arab States, therefore Lebanon closed its borders in March and only allowed women and children with approved visas to enter the country.[9] Even though most Lebanese consulates refused to give visas to anyone that applied, Palestinian soldiers and civilians alike ignored any restrictions placed by the AHC and continued to flood into Lebanon. The overabundance of former military refugees did not go unnoticed by the new generation of Palestinians growing up in refugee camps.

Lebanon’s attempts to reintegrate former soldiers into military service worsened communal tensions between different generations of Palestinians. The Palestine Post, founded in 1932 by Gershon Agronsky, published an article on May 5th, 1948, that outlined Lebanon’s plan to reorganize and limit the number of Palestinians within the country. This strategy was unveiled by the Lebanese Public Security in Beirut and called for all Palestinian soldiers to find the nearest military outpost so they could bear arms once again against Israel. Those staying in Lebanon would still need to own an AHC card, especially military aged men. Former Palestinian fighters ignored Lebanon’s call because they were unwilling to force themselves back into a war they narrowly escaped and had no guarantee of an Israeli defeat.[10] Some Palestinians did go back to their military obligations, but not enough to control the rising number of refugees entering Lebanon. Their reluctance caused the Lebanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) to put more pressure on civilian refugees to enlist, as a result younger Palestinians began blaming the older generation for igniting Lebanon’s aggression.

Palestinian soldiers’ refusal to resume their military service brought more harm to younger refugees in Lebanon, solidifying a generational divide based around nationalistic action. One day after the previous article was released, The Palestine Post unveiled a follow up report on Lebanon’s rising refugee population. Every day brought more refugees that easily circumnavigated the border restrictions placed by the AHC due to their numbers overwhelming border security. “Officials estimated that at least 30,000 Palestinian Arab refugees are now in Lebanon, crowding the hotels, schools, camps, and hospitals.” The article then wrote how every Arab state that took in fleeing Palestinians intended to “mobilize all the refugees between 18 and 50…for training in combat and non-combat duties.”[11] This update confirmed two key pieces of information; one that because a substantial portion of Palestinian soldiers ignored Lebanon’s call to rejoin the military the refugee population rose by over 10,000 people in just two months, and two that the AHC decided the best way to diminish the refugee population was by enlisting all military aged men. The younger generation was being dragged into active service by Lebanese authorities to compensate for the older generation’s reluctance, displaying how Lebanon’s borderlands made a preexisting divide worse.

Personal deniability was another critical component that contributed to former soldiers being isolated from their community. Kamil Ahmad Bal’awi, born in 1928 in Shafa ‘Amr, was a Palestinian soldier who abandoned the town of Tarshiha after his commanding officer ordered everyone to retreat into Lebanon. In an interview led by Amira ‘Alwan, he asked if the young men that lived in Tarshiha stayed behind to defend their home while Kamil and his regiment left, to which Kamil confirmed they did. “Soldiers couldn’t do much in this situation. The officer was in charge of them. When the officer ordered them to retreat, they had to do so.” Amira then asked Kamil if he felt like he was betraying his fellow Palestinians. “No. Soldiers like us didn’t feel that way. Betrayal can only result from the high commanders, the very highly ranked officers. We didn’t feel that way.”[12] Kamil’s statements argue that the chain of command prevented him and his fellow soldiers from protesting their orders, thus any accusations of cowardice should not be directed towards him. These types of explanations however were perceived by younger Palestinians as blame shifting attempts, which put distance between them and the older generation.

Survivors of the Nakba who had no military obligations were equally open to being ostracized from their community by the new generation. A hypothetical question Bushra asked Fifi towards the end of their interview was if she could go back to 1948, would she have stayed in Yafa instead of fleeing. After some time to ponder the inquiry, Fifi responded. “With my current life experience, I would not have left. Or maybe I would have anyway because those who remained there until now are not dignified…How do you say? Like second class.” Fifi later clarified how she had grown accustomed to the younger generation blaming older refugees for abandoning Palestine and ridiculing them for their inaction. Because of their accusations she was unsure if staying and risking her life would have made much of a difference to how young Palestinians view the older generation. Fifi’s father, despite advocating for the municipality of Yafa to capitulate, stayed behind and died while defending Yafa from IDF soldiers. His sacrifice did little to stop younger Palestinians from belittling his daughter.[13] After Fifi fled Yafa the same feelings of mistrust and tension did not fade away, rather it carried over into Lebanon and turned into a divide between different generations of Palestinians.

The older generations’ lack of participation in nationalist activities promoted the idea that adult Nakba survivors had no desire to help young Palestinians reclaim their homeland. Archeologist and historian Rayyar Marron argues that Palestinians who were old enough to survive the Nakba yet unwilling to recount their stories were not held in high esteem. Refugees and former soldiers that lived through their exodus into Lebanon but stayed away from involving themselves politically were referred to as being “unconscious” by the jeel al-nakba, or the generation of the disaster. This dismissive term encompassed the old generations’ reluctance to get involved in militant activities in fear of the repercussions they might face from Lebanese authorities. In comparison, the jeel al-nakba viewed themselves as true Palestinian nationalist and valued stories centered around the Nakba, therefore they kept these retellings alive and used them to curate a contemporary refugee identity.[14] Survivors that hesitated to share their stories were looked down upon by the younger generation because they believed these individuals cared more about protecting themselves than helping their cause. This tension left many older refugees disconnected from their community following their representation as passive traitors.

Mental trauma from the Nakba and being actively avoided by the community caused older generation Palestinians to seek self-isolation. Historian Rosemary Sayigh argues that not only did the jeel al-nakba disassociate themselves from the old generation by judging and attacking their resigned piety, but that older refugees willingly distanced themselves. Adult Nakba survivors experienced intense feelings of shock, mourning, and loss of self-respect because of criticisms that stemmed from the jeel al-nakba. Attacks like these exacerbated mentally harmful memories and experiences that happened during their displacement, consequently leaving no safe environment or connections where older refugees could unload their trauma.[15] These strong emotions increased their sense of “otherness” and forced many Palestinians to self-isolate themselves from their fellow community members. The old generation became disconnected because the polarizing communal space within Lebanon’s refugee camps offered no social spaces that survivors from the Nakba could openly express their turmoil.

Gender Dynamics

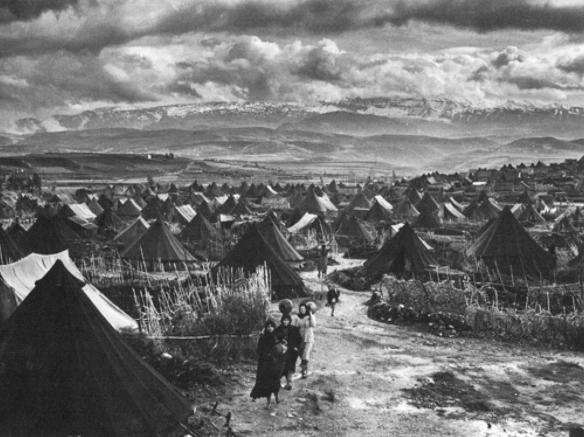

The miseries of life in Lebanese refugee camps were a consequence of the country’s political and social circumstances following the Arab-Israeli war. By the end of 1948, around 110,000 Palestinian migrants had entered Lebanon and were placed into makeshift camps, the majority of which consisted of shelters built from tents and shacks using flattened petrol cans. It was envisioned that these temporary living quarters would be enough until a solution to the refugee problem was found. This changed when the Israeli government began absorbing Palestinian land and property into their economy, blocking any resettlement plans for displaced Arabs. Lebanon’s MFA instead had to manage and create new policies for the refugees stuck in their country, as returning them to their homes was no longer a possibility. Opportunities for Palestinians to find better housing outside their encampments were limited by the MFA because they believed an influx of Muslim Arabs would encroach on Lebanon’s Christian population and threaten their living parameters. Refugee camp living conditions slowly deteriorated as a result and Palestinians makeshift homes took on more permanent features. Before long, slabs of concrete blocks formed dwellings that functioned as schools, hospitals, and homes for the imprisoned.[16]

Myrtle Winter-Chaumeny. Naher al-Bared refugee camp, near Tripoli (Lebanon). 1952.

Adult males’ isolation combined with the wartime deaths of men left many young Palestinians in need of new communal leaders, a position that women started occupying. One responsibility that Arab women inadvertently took on was carrying on the memory of Palestine. Umm Ghassan, a 60-year-old survivor from the Arab-Israeli war, often told her story to other Palestinians while living as a refugee in Lebanon. During one of her retellings to an interviewer, Umm Ghassan recounted the moment IDF planes and mortar fire started targeting her home, forcing herself and her two children to flee. “There were planes and cannons shelling us. We ran away. [My husband] stayed at home, he refused to leave. Just me and the kids left. And we came [sighs] to Lebanon.” Umm Ghassan finished her short story by saying “I wish we had died rather than come here.”[17] Despite making it into Lebanon, Umm Ghassan voiced her regret after experiencing life in Lebanon as a refugee, a sentiment that gained her favor among young refugees. Women that shared their survival stories and chronologized Palestine’s history kept them safe from being disconnected by the younger generation.

A generational divide between women storytellers also existed and altered the type of stories that were shared with other Palestinians. Sayigh argues that older women told stories about their lives before the Nakba and during their exodus from Palestine, while younger women focused more on the Palestinian struggle in Lebanon and of camp life. Umm Ghassan was one of the only storytellers from the “generation of Palestine” in her camp that spoke about examples of the Lebanese army suppressing activist demonstrations, aligning herself more with younger women’s stories since those narratives encompassed their earliest memories. The younger generation tended to avoid familial connections and focused more on street life, school, public demonstrations, episodes of Lebanese violence, and political activities.[18] These differences indicate that young women storytellers suppressed their personal lives to become more active in public communal activities, while older women’s stories were centered around the household and their roles as mothers or daughters. Due to Lebanon’s hostile environment and the absence of traditional male figures, women across all ages achieved new social status within their refugee camps, yet a generational difference preserved the divide between storytellers and the Palestinian people at large.

The cowardice associated with soldiers’ survival meant that women’s escape stories were viewed more favorably by the community. Subhiya Salama, born in al-Zahiriyya which is found in the northeastern sector of modern-day Israel, was with her children and sister-in-law, Nazha Salama, when IDF soldiers attacked their town. While escaping for the enemy, Nazha was gravely injured by an Israeli landmine and needed Subhiya to carry her. Yet Nazha pleaded to be left behind. “Please just throw me here and go,” said Nazha according to Subhiya’s retelling. Subhiya then spoke about the moment IDF soldiers spotted them. “They showed up in front of us, just like that. So I dropped her off right there…As soon as I turned around, I saw them stabbing her with knives.” When Subhiya recounted her story to other refugees she was viewed as a courageous hero, even though she abandoned Nazha.[19] This reception stands in contrast to how former soldiers were ridiculed for their survival stories, showing how women replaced men as role models for bravery. The change in gender roles amongst Palestinian refugee camps kept male stories distant from the community’s cultural identity.

Palestinian women also distinguished themselves from male refugees because of their memory for pre-1948 traditions. Sayigh claims that women’s self-narratives were used to keep track of Palestinian history and reflected the changed gendered dynamics. In comparison, men’s stories lacked information about cultural significant components in relation to Palestine. Despite women’s stories varying in subject matter between the old and new generation, a common “struggle personality” appeared that emphasized rural Palestinian women’s strength, courage, and resourcefulness. Positive representations of women also kept certain pre-1948 traditions alive, such as maintaining a deep connection with the natural landscape, and were then used against Lebanon’s MFA, who were trying to keep such cultural ideas and memories suppressed.[20] Refugees used their admiration and newfound respect for Palestinian women to counter negative perceptions held by native Lebanese residents. Women became keepers of history and were held in high regard for their wealth of knowledge for events before and during the Nakba, creating a clear hierarchical divide within the older generation based on gender.

Women’s responsibility to remember and uphold Palestinian traditions conversely created a contradiction with their new social status. Gender specialist Deniz Kandiyoti argues that women who preserved pre-1948 relations of kinship and locality created cultural contexts that opposed changing gender dynamics. This paradox formed during the 1960’s when Lebanon infiltrated refugee camps for information gathering missions and to promote a fear of intrusion campaign. Rumors of women being unfaithful to their husbands were spread by the Deuxième Bureau, Lebanon’s intelligence agency, to disrupt Palestinian resistance movements. Internal acts of gendered violence rose as men began targeting women who were suspected adulterers or Lebanese informers. These attacks were then concealed by the whole community to try and mitigate more internal divisions. Women for their part continued to embolden men as household and communal leaders because it was a point of pride for refugees. Retaining such expectations reinforced a particular Palestinian identity that opposed Lebanon’s attempts to dismantle their way of life.[21] This paradoxical identity was thus formed out of a necessity to protect against Lebanese aggression that threatened to cut off Palestinians from their heritage. Palestinian women, while gaining notoriety and social prowess, were unable to break completely free from their pre-1948 gendered roles due to Lebanon’s authoritative actions.

Jobs outside of refugee camps, while difficult to acquire for both genders, were more widely available to Palestinian women due to gendered policies. In September 1948, ‘Adil was living in one of Lebanon’s refugee camps and had been surviving off the money he saved before being displaced. Occasionally ‘Adil found some temporary jobs, but it was never enough to stave off the threat of starvation. “We have 60 more Palestinian liras and 70 Lebanese liras,” proclaimed ‘Adil in a letter sent to his family still living in Palestine. “After that there would be no other option but to starve to death.” Marwa, another refugee living in Lebanon, echoed this sentiment in letters sent to her family. “I often work so we can keep living. There is no way to live but [taking on temporary] daily work.” While Marwa’s situation painted an equally dire picture, she noted that daily work had become a part of her daily routine. Older men had a harder time getting jobs because businesses were afraid that they could be former soldiers hiding from their military obligations, so if they were hired and caught the owners would be accused of harboring criminals.[22] Palestinian women navigated Lebanon’s job restrictions more effectively and became the main providers for their families while men were viewed as financially unreliable.

Male refugees were viewed as comparatively lazier to native working citizens by Lebanese authorities, who popularized the idea that unemployment was caused by Palestinians lack of drive. In 1950, Lebanon’s MFA approved the recruitment of several Palestinian teachers, majority of whom were women, to work for the Government of the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman. Among those approved for this job transfer was Mohammed Iberhim Huneidi, who had been selected for his leadership skills and work performance. According to the report, Mohammed was chosen because of his “high energy and interests which are in contrast to the lack of enthusiasm shown by many other Palestinians.”[23] Mohammed’s defining attributes prove that the Lebanese government viewed male Palestinians as shut-ins and blamed them for rising unemployment rates. This negative outlook was supported by the considerable number of former soldiers who stayed in hiding to avoid being reenlisted into the army. Fear of reenlistment was used by Lebanon’s leadership to associate laziness with Palestinian men, therefore giving them a scapegoat for their unemployment problems and providing women more employment.

Lebanese propaganda diverted the fault of unemployment onto Palestinian men to keep them divided from their community, when in fact the issue was entirely of the country’s own making. In 1950, the Commonwealth Relations Office (CRO) and the Middle East Committee (MEC), departments that managed Britain’s relationship with its former colonies, exchanged several letters between one another about the economic impacts of refugees living in Lebanon. One correspondence pertained to how Palestinians heightened Lebanon’s unemployment rates, not because of their supposed laziness but because the government restricted their job access. “The trend threatens to deteriorate dangerously unless increased opportunities for earning a livelihood are provided. Their continued presence in the country…would aggravate a situation which exists independently of them.”[24] The influx of Palestinian refugees into Lebanon made an already unstable economic situation worse, however they were not the root cause of such a problem and had in no way been more problematic due to their unwillingness to find jobs. Lebanon had the opportunity to open their job market to the refugee population but decided against it to preserve a sense of national security. The living conditions of refugee camps in Lebanon skewed gender relations in favor of women and kept men socially distant.

Religious Tensions

Like gender, religious affiliation became a significant divider for Palestinians bound to Lebanon’s rules and regulations. Refugee policies that targeted and segregated Muslims began under Bechara El Khoury, president of Lebanon between 1943 to 1952, but increased in severity following the Lebanese Turmoil of 1958. This crisis was caused by El Khoury’s replacement Camille Nimr Chamoun after he endorsed the Eisenhower Doctrine, allowing Lebanon to call upon economic or military aid from the United States. Lebanon was the only Arab government to accept this doctrine and consequently received condemnation from Muslim leaders across the Middle East. Refugees especially harbored anti-Chamoun sentiment because of his unwillingness to use Western aid towards improving refugee camps. Upheaval against Chamoun’s rule reached a breaking point in 1958 after a series of killings between anti and pro-Chamoun supporters, forcing the U.S. military to temporarily occupy Lebanon and moderate Fouad Abdallah Chehab’s inauguration as the next president. Fearing lingering resentment against Chamoun’s government, Chehab used the Deuxième Bureau to control and police Muslim refugee camps. Muslim Palestinians needed permits to visit non-Muslim camps, were forbidden from reading or listening to the news, and were restricted to appointed public water sources. Officers also used these policies to harass, extort, and arrest Palestinians daily, creating a precedent for targeting Muslims refugees.[25]

Lebanon’s religious persecution against Muslim refugees limited job opportunities for both Palestinian men and women trying to find stable income outside their encampments. Historian Shay Hazkani argues that Lebanon’s MFA denied Muslim Palestinians access to working permits and citizen ID cards to protect the country’s religious demographic. These specifications were implemented to ensure that the Christian population would not be pushed out of the job market. This system also limited where Muslim refugees could traverse to in Lebanon, restricting their movement to within the confines of refugee camps as to prevent them from buying permanent apartments or property. As a result, Muslim refugees like Marwa could only find temporary jobs that did little to improve their situation. Palestinian Christians on the other hand did not suffer the same restrictions and were instead granted Lebanese citizenship when asked. Christian refugees could even receive state funding to start their own businesses in the larger cities.[26] Since Christians equated to only thirty six percent of the total refugee population displaced into Lebanon, their integration posed less of a threat to the country’s religious demographic. Lebanon’s leniency towards Christian refugees over Muslims created a clear separation based around religion within the Palestinian community.

Lebanese politicians manipulated refugee policies against Palestinian Muslims for their own benefit and to gain the support of Palestinian Christians. El Khoury originally allowed Palestinian Muslims unrestricted access into Lebanon as a strategy to improve public support among Lebanon’s Muslim communities, which proved successful at first. El Khoury then reinforced this sentiment by supplying financial support to several humanitarian groups that were tasked with keeping refugee camps supplied. However, this changed when El Khoury realized the overwhelming number of refugees that would enter Lebanon as Israel continued to push their offensive. Fearing what a massive influx of Muslims could do to Lebanon’s voting demographic, the Lebanese Government enforced sectarian policies to keep the Muslim refugee population held in designated zones. This separated Lebanon’s refugee camps around religious affiliation, forcing Palestinian Muslims and Christians to live in different camps rather than coexisting next to one another like back in Palestine. Monetary endowments were also split in favor of Chrisitan organizations and left many newly formed Muslim associations, most of which relied on support from El Khoury, with the arduous task of managing a much larger refugee population with a fraction of their financial aid.[27] Lebanese sectarianism divided Muslims and Christians from one another to better manipulate where their humanitarian aid went to.

Pre-1948 religious distinctions worsened in Lebanon due to the MFA’s religious preferences. Urban and rural residency in Palestine was the most significant factor that differentiated Palestinians from one another prior to their displacement. The urban population consisted of mostly middle-class Christians and Sunnis while the rural population held primarily Shi’ites peasant workers with Druze components. This distinction created a class line between diniyeens, the urbanities, and fellaheens, the peasants. Such discrepancies became more prominent when Palestinians from both groups were displaced into Lebanon. Diniyeens had an easier time settling into major Lebanese cities due to their business and familial connections, as well as possessing skills that allowed them to acquire new urban jobs. In contrast, the fellaheen had no significant connections with the outside world, due mostly to their agricultural profession, and their farming skills proved ineffective in helping them find employment.[28] Adding more to their isolation in Lebanon was the fact that the religious composition of Palestinian peasants was a minority in comparison to the Sunni and Christian population. These class distinctions meant that when Shi’ites entered Lebanon, they were the most cut off group, both from the Lebanese people and their own community.

Sectarian religious policies also derived from Lebanon’s mismanagement of other refugee catastrophes and their inability to find an agreeable solution on how to support the Palestinians while advancing plans for their resettlement. In 1949, Harry S. Truman, a member of CRO, assessed Lebanon’s ability to support the influx of Palestinian refugees that had entered the country following the Arab-Israeli war. Truman discovered that Lebanon’s overpopulation was caused by their willingness to absorb refugees from catastrophes prior to the Nakba, like the Armenian genocide. This left the government with barely any room to supply aid exclusively to Palestinian refugees. Additionally, Lebanon’s MFA were unable to come to any agreement on resettlement because of their limited financial options, which was so severe that even the full economic development of Lebanon would not solve the issue of religious bias. “In that case employment might be available for a small number of Palestinians, mainly of the urban type.”[29] Regardless of Lebanon’s economic situation, prejudice against rural Muslim refugees would still limit job opportunities for Palestinians. Religious segregation barred most Palestinian refugees from finding careers that would improve their living conditions.

Lebanese Christians took after their government’s sectarianism and kept Palestinian Muslims segregated. British Minister Houston-Boswall conducted a report on Lebanon’s refugee crisis during the Summer of 1948 and discovered that Lebanese Christians echoed the hostilities their government held against Muslim refugees, so much so that they blocked all resettlement plans in Lebanon for Palestinians. According to Boswall, Christian citizens affirmed that they “would resist any attempt to [permanently] resettle refugees in Lebanon.”[30] Lebanon’s pre-existing religious demographic created a unique problem, because while other Arab States with a Muslim majority could resettle Palestinians in their territories if they wanted, Lebanon’s religious makeup obstructed this choice. Furthermore, Israel’s own reluctance to approve Muslim reintegration meant that Lebanon had to keep most Palestinian refugees within their designated zones. All these factors resulted in Palestinian Muslims being perceived as a threat to Lebanon’s security that had to be divided from their community and controlled. The aid of Christian public sustained the Lebanese Government’s authoritative policies of religious segregation.

Christian communities also deteriorated the communal dynamics between Sunni and Shi’ites refugees to bolster their own societal standings. Historian Asher Kaufman claims that Lebanese Christians used their government’s religious bias to gain a stronger position over their Muslim counterparts, who were becoming more of a concern due to the influx of Palestinian Muslims. By the 1960’s, most Palestinian Christians and some Sunni urban workers had received Lebanese citizenship IDs or working permits, however rural Sunnis and Shi’ites were rarely offered the same benefits to escape their circumstances. Shi’ites especially were the smallest group in Lebanon and had no major political or social backing, thus they had no connections outside their religious affiliation. This allowed Lebanon’s Christian demographic to develop more connections and influence while the country’s Muslim population remained stagnant. One possibility available to higher social stratum Sunnis was marrying into or offering payoffs to Chistian families to obtain legal citizenship, subsequently severing their connections with other Palestinians while supporting Lebanese Christians.[31] Lebanon’s refugee policies were used by native Christians to gain more influence while also provoking Palestinian communal divisions.

Contrary to the narrative being expressed, Lebanon’s religious segregation did not prevent meaningful connections across different faiths from developing. During an interview between Nafez Nazzal and Umm Joseph, a first-generation Palestinian refugee who lived in the Christian camp of Dbaya, a friend of hers stopped by to commemorate their friendship. Umm Joseph’s acquaintance was a Lebanese Muslim who befriended her when they were traveling outside their refugee camp, a privilege only allowed to Christian refugees.[32] Their friendship countered the idea that Lebanon’s sectarianism prevented positive relationships from forming between both communities. However, it is important to note their individual circumstances, Umm Joseph being a Christian Palestinian meant she was not chained to the confines of her refugee camp unlike her fellow Muslim neighbors. Likewise, her Muslim friend being a native-born citizen meant she was unobstructed from all the religious restrictions placed on refugees. Had Umm Joseph been born a Muslim she never would have lived in Dbaya and would instead be restricted to a Muslim refugee camp. Positive connections that did form in Lebanon only did so because they maneuvered around the restrictions that Lebanon’s MFA implemented.

The divisive policies and environment that Lebanon’s borderland promoted led to many Muslim Palestinians actively isolating themselves from the Lebanese people. Historian Adel Manna argues that Palestinian’s tendency to nurture the idea of returning to Palestine increased when refugee camps were prevented from integrating with Lebanese neighborhoods. Seeing that they were powerless to overcome religious divisions placed by Lebanese authorities, Palestinian Muslims accepted their isolation from their fellow Christian neighbors and community members. This acceptance allowed Palestinians with a nationalist mindset to strengthen their collective desire to return home and leave behind those who disconnected themselves from Palestine.[33] Segregation suited both Lebanon and Muslim refugees who had lost any sense of compassion for one another, therefore neither side made any moves to alleviate tensions or reconnect communal relations. Rather than confronting Lebanese hostility, Palestinians kept to themselves and remained focused on trying to reignite their national identity.

Lebanon’s MFA prioritized returning Christian refugees back to Palestine over Muslims to gain more international support. On October 4th, 1949, Francis Offner, a writer for The Palestine Post, authored an article detailing the first organized group of Palestinian repatriates that would be returned to their homes. This first grouping was personally supervised by the Archbishop of Haifa, George Hakim, and consisted of 150 displaced Christian orphans, 100 girls and 50 boys. Offner’s report also included comments made by the Christian dignitaries about their hopes that future resettlement plans will “see the majority of the Christian.”[34] Despite covering the refugee crisis in Lebanon this article made no mention of Muslim refugees or plans for their resettlement. Considering how Lebanon treated Christian refugees more favorably, the first group of repatriates consisting of only Christian children shows Lebanon’s religious bias. Comparatively there were far more Muslim children with less options to live comfortably during their displacement in Lebanon, yet Christians were still given priority. This gesture granted Lebanon good faith in the eyes of international viewers while they continued to keep Muslim refugees separated from their community in Palestine.

Even when Lebanon started resettling Muslims back into Palestine, they continued to keep all remaining refugees separated and secure within the confines of their camps. On November 25th, 1949, The Palestine Post revealed that 770 women and children, majority of whom were Christians, had been approved by Lebanon and Israel to be transported back to their homes from the refugee camp in Tyre, a city on the western coast of southern Lebanon. This was one of the first repatriate excursions that included non-Christian refugees, and as a result Lebanon’s MFA released a statement reminding Muslim refugees that this arrangement did not grant them permission to make their own way across the border. Fearing a surge of Palestinians breaking from their designated refugee camps, Lebanon affirmed that any refugee caught illegally crossing the southern Lebanese border would be punished and returned to Lebanon.[35] Tensions between Israel and Lebanon were still high after the war’s conclusion, so to prevent more problems from arising the government took a hardline stance against refugees trying to leave their encampments. Lebanon’s strict reaction shows that they repatriated mostly Christians because they encompassed a minority of the refugee population and posed less of a risk in instigating actions considered rebellious.

Lebanese prejudice against Palestinian Muslims was so severe that even former refugees cut themselves off from their community. On May 24th, 1964, Philip Hochstein, writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer, published an article discussing examples of Lebanese prejudice against Palestinian refugees. The report noted that not until 1963 did Lebanon promise employment rights to Palestinians, yet that promise stood unfulfilled a year later. “More to the point is the very evident prejudice against the refugees in all quarters,” said Hochstein when discussing how Palestinians were viewed. “It is to be found among Moslems, [sic] as well as among Christians, and it is to be found most emphatically of all among ex-Palestinians who have managed to make their way financially and express an actual loathing for their fellows.”[36] Since Christian and urban Sunnis were the only Palestinians that could earn a profitable life in Lebanon, rural Muslims and Shi’ites became the most marginalized religious groups. Their social status was perceived with such disgust that former Palestinian refugees disassociated themselves completely from those still living as refugees. Lebanon’s preferential treatment was so oppressive that Palestinians who benefitted refused to reconnect with their former community.

Communal Realignment

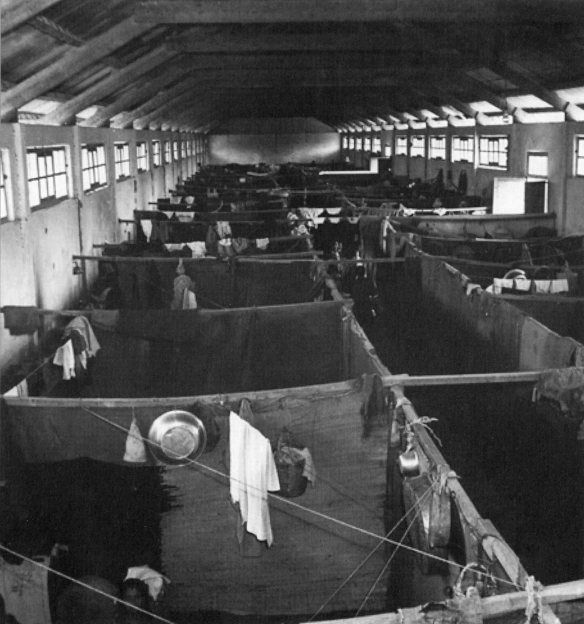

Lebanese persecution against Palestinian refugees dragged on for so long that any hope for repatriation or improvements to their camp life were diminished. By the 1950’s, groups of Palestinian intellectuals started gathering in Beirut to discuss different political doctrines that they believed would help the Palestinian cause in Lebanon. Variations of Marxism, Ba’thism, and Pan-Arabism were shared as potential ideologies that could solve the refugee problem and regenerate Arab society entirely. These proposed solutions still hinged on the host government’s support and approval. Heading into the 1960’s, Lebanon and every other Arab state continued to undermine the Palestine people’s plight while appeasing international viewers with statements that changes were on the way. The Arab League’s creation of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1964 for example was merely used as a tool to restrict Palestinian movement and resistance activity in host countries, which had steadily been rising as their conditions worsened over the years. Much like the few refugees who could escape their confinement in Lebanon, the PLO’s executive council was composed of Palestinian nobles who knew little of the refugee camps dire conditions.[37] This never-ending neglect perpetuated more misery amongst Palestinians and heightened their resentment.

Mia Mia camp, near Sidon (Lebanon), 1952.

Palestinians’ communal coherence fractured during the Nakba and continued to be torn apart thanks to Lebanon’s leadership prioritizing their self-preservation. John Zakarian, a Palestinian editor for The Edwardsville Intelligencer, wrote an article on June 15th, 1967, that discussed Lebanon’s vicennial reluctance to offer more employment opportunities and citizenship for Muslim refugees. Zakarian referenced Lebanon’s religious demographic as the main contributor for why Lebanon stayed steadfast in denying aid to most Palestinians. “Its delicate 50-50 balance between Christians and Moslems [sic] would be upset by granting the refugees, 90 percent of whom are Moslem, full rights.” One area Zakarian discovered some meaningful development was regarding education, but despite this Lebanon still restricted Palestinian movement to their refugee camps.[38] Lebanon’s MFA continued to deny Muslims any resources to alleviate their dire circumstances after almost two decades from their displacement, only expanding on their academic resources to appease international viewers. Lebanon’s abrasive refugee policies sewed discourse and split the Palestinians apart in a literal sense, however these same acts of oppression would be used by Palestinians to reconnect themselves.

The misfortunes that Palestinians faced while living in Lebanon’s borderlands worsened to such severity that it eventually reunited parts of their community under a mutual struggle against Lebanese oppression. Julie Peteet, professor of anthropology at University of Louisville, argues that Lebanon’s unwelcoming environment created a distinct Palestinian identity that was formed around a common sense of suffering and collective memory of Palestine. Separations based around generational conflicts, gender roles, and religion had all been heightened because of Lebanon’s mismanagement over the refugee crisis. Logistical problems that Lebanon consistently neglected, such as providing enough food and living space, added more fuel to Palestinians unanimous frustration against their host country. These misgivings, according to Peteet, were used by refugees to recontextualize their daily existence into a larger national narrative and common history.[39] By reinterpreting their suffering, segregated groups like older generation Palestinians who fled Palestine or Christians that received better treatment were blamed less for their actions and viewed instead as a consequence of Lebanon’s wrongdoings. This concept allowed Palestinians to appropriate their abuse and transform it into a single cultural goal that all refugees could rally behind. The miseries in Lebanon that had once divided the Palestinians were instead used to bolster a collective memory and communal identity.

Limited resources originally forced Palestinian refugees to separate themselves from their fellow neighbors for the sake of survival; however, this problem eventually turned into a tool for reunification. Following documentation by The Beirut Daily about reports of mass starvation amongst refugee camps in Lebanon, The Palestine Post released an article on July 13th, 1948, that supplied first-hand accounts from Palestinians about their living conditions. These findings included a letter by Akal Assad, a Haifa Arab who was displaced into Lebanon, that divulged his living conditions. “I am the father of ten children. I came to Lebanon and was promised the support of its government. After three months my family is starving.” While writing this letter, Akal used the opportunity to make a public plea for help. “I declare that I am ready to sell four of my sons to whoever will undertake to find me food to save the rest of my children.” Akal’s final words in his memorandum captured his pure bewilderment of the situation he was in, “We cannot believe that the Lebanese authorities deny us the rights accorded to our Egyptian and Syrian brethren just because we are refugees.”[40] As starvation rates rose in the following years, so too did refugee violence against Lebanon’s local authorities. The government’s reluctance to supply refugee camps sufficient food stuffs brought Palestinians together to take forceful actions instead of remaining docile in their starvation. This surge of conflict foreshadowed how Palestinians would begin reconnecting themselves through anti-government demonstrations and actions.

Lebanese negligence and aggression slowly encouraged Palestinians to stage unified attacks against military buildings to advance refugee policy reformations. Several armed attacks occurred throughout the 1950’s within Lebanon that originated from refugee camps housing rural Palestinian Muslims. These violent confrontations ignited because of food shortages and more aggressive policies that limited freedom of movement in refugee camps, thus most of the attacks took place near military checkpoints. “Another attack by a band of 60 armed men occurred on the Mashgara Gendarme Post in Southern Lebanon,” wrote The Palestine Post on July 7th, 1949. “The Government is taking vigorous action and has arrested over 200 people. It was stated that the bands comprise many Syrians and Palestinians.” The news article also cited Lebanon’s closed border policy as another contributing factor that initiated these armed confrontations.[41] Violent attacks against Lebanese institutions of power functioned as a tool that Palestinians used to band together and resist their forced separation. This strategy relinked Palestinians, as well as other refugees, under the common goal of forcing Lebanon to make meaningful changes that improved the living standards of refugee camps.

Lebanon’s political motivations outside the country revealed to Palestinians that change would not occur even from outside pressure. On September 22nd, 1949, The Palestine Post released a report covering El Khoury’s statements on Lebanon’s dedication to their fellow Arab States. “President El Khoury said that Lebanon intends to support friendly relations with the Arab States, because of his awareness of the new element-Israel- ‘intruding’ in the Middle East. ‘We will do our duty in regard to Palestine.’” This announcement was made in lieu of criticism from other Arab States about Lebanon’s lack of commitment to countering Israeli threats and supplying equal provisions to Muslim refugees. To dissuade these sentiments, El Khoury reaffirmed Lebanon’s position as a cooperative ally to their Arab allies, yet his comment on what the government would do concerning Palestine remained vague and ambiguous.[42] El Khoury’s statement signaled to Palestinians that nothing would change in their favor since he was only interested in relieving Lebanon from international pressure rather than helping the country’s refugee population. This demeaning attitude towards the concerns of refugees had taken over Lebanon and was used by Palestinians to curate a new communal identity that opposed Lebanese authority.

The MFA’s dismissive attitude towards the plight of refugees curated a common enemy mentality that Palestinians used against international political figures. In the 1950’s, Lebanese shelter programs garnered protests from refugees because of their potential that they would “liquidate” Palestinians desire to return home by permanently resettling them in makeshift dwellings. Political representatives in Lebanon, such as Prime Minister Karame, insisted that the aims of the agency were “misunderstood by the refugees” and that “an improvement of their living conditions does not at all mean their final resettlement.” These concerns were partially mitigated by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) thanks to their ability to supply sustainable resources. Such efforts, however, were incapable of solving the MFA’s complacency.[43] Lebanon’s leadership consistently used lies and misrepresentations to cover up their actions that were meant to keep Palestinians in a state of disarray within their camp dwellings. Palestinians in turn acknowledged their concerns were being ignored by Lebanese authorities and that the only means to enact change would come from their reunification.

Palestinian refugees weaponized their collective suffering to cut through Lebanon’s humanitarian facade. On July 1st, 1959, Arizona Republic released a news report covering a hunger strike being organized by Palestinians in Lebanon. This protest was set to take place during U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold’s visit to Lebanon, who a year prior had promised to enact a program that would hasten resettlement plans for Muslim refugees. His presence to the Palestinians was nothing more than a reminder of the lies he said in the past. “Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are planning a hunger strike this week…The Arab broadcast said the hunger strike would protest Hammarskjold’s recent statement that it would take a good deal of time to return the refugees to their homes.” Hammarskjold was a known ally to Lebanon and rarely made any significant headway in returning Palestinians to their former homes, thus these hollow promises enraged the refugees who were always being told by authorities that drastic changes were happening.[44] Palestinians purposefully starved themselves to openly oppose Hammarskjold’s string of blatant lies, turning hunger into a tool that unified their community when it previously split them apart. The circumstances that divided the Palestinian community had been transformed into an opportunity to undo the damage that Lebanon’s borderland caused.

***

The Nakba in 1948 tore apart the Palestinian community and left Palestinians in a state of disarray upon entering Lebanon. Instead of finding sanctuary from foreign hostility, Palestinian refugees found themselves in an equally harsh landscape that brewed more internal divisions and conflicts. It was only after countless repeated offenses that a new cultural identity had solidified and unified enough refugees to relink their sense of community, though a sizable part of their population still experienced severe isolation. By the 1970’s Palestinians living in Lebanon took center stage in the Lebanese Civil War and battled against right-wing Christian militias, a coalition that supported suppressing Muslim refugees in years prior. Lebanese Muslims on the other hand started openly advocating for Palestinian rights and acting against their government’s authoritative refugee policies.[45] For every group that stayed steadfast in their desire to keep the Palestinian community separated, another overcame that barrier and developed new connections during the violence that ensued. This conflict did not mark an end to the Palestinians struggle within Lebanon, rather it highlighted how Lebanon’s leadership failed to keep the Palestinian community separated and docile.

The Palestinians communal coherence upon being displaced into Lebanon suffered major divisions based around generational conflicts, shifting gender roles, and religious affiliations, however such conflicts also relinked their community under a new cultural identity. For historians, the question whether Palestinians themselves or exterior forces were more responsible for how Palestine’s sense of community altered has always been a complicated point of disagreement. An argument for either side presents its own unique set of problems, therefore any interpretation that tries to supply a fulfilling answer must scrutinize how each group reacted to their circumstances. An equal consideration for the borderland itself is also needed, as Lebanon’s environment held a notable set of attributes that affected how the Lebanese people and Palestinians interacted with one another. Lebanon’s borderland, much like the people that inhabited it, was a force that reacted to the social and political developments taking place.

Stories like Amina’s were common amongst survivors that were displaced into Lebanon, yet their lives after the Nakba are not as widely known because of the isolation they experienced. Their untold stories reveal how Lebanon’s negligence stoked the flames of a beaten and abused people, causing the community to unravel itself. Reflecting on all the relevant history, one must acknowledge the Palestinians perseverance to hold onto their sense of identity and capability to manifest a miracle of cultural survival. The notion that the same forces that pushed Palestinians away from one another would also bring them together seems equally as miraculous, if not more confusing. Regardless, their endurance defied the forces in Lebanon’s borderlands that tried to suppress the existence of a people uprooted from their home, ensuring that the question of Palestine will continue and renew itself in time.

Bibliography

Allan, Diana. Voices of the Nakba: A Living History of Palestine. London: Pluto Press, 2021.

“Arab Families to Come from Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. November 25, 1949.

Bramwell, Anna C. Refugees in the Age of Total War. London: Routledge, 2021.

Cleveland, William and Martin Bunton. A History of the Modern Middle East. New York: Routledge, 2016.

“Crisis in Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. July 13, 1948.

“Druze Fight in Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. July 7, 1949.

Government of Oman. File 11/32 IV Palestinian Arab Students as teachers for Muscat Govt., 1950. British Library: London.

Hazkani, Shay. Dear Palestine: A Social History of the 1948 War. Stanford University Press, 2021.

Hochstein, Philip. “Pride and Prejudice in Mideast: Refugees Cost U.S. $350 Million.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. May 24, 1964.

Kandiyoti, Denzi. Gendering the Middle East: Emerging Perspectives. New York: Syracuse

University Press, 1996.

Kaufman, Asher. “Between Palestine and Lebanon: Seven Shi’i Villages as a Case Study of Boundaries, Identities, and Conflict.” The Middle East Journal 60, no. 4 (2006): 685- 706.

“Lebanon Denies Invasion.” The Palestine Post. May 6, 1948.

“Lebanon Will ‘Do Her Duty’.” The Palestine Post. September 22, 1949.

Manna, Adel. “The Palestinian Nakba and its Continuous Repercussions.” Israel Studies 18, no. 2 (2013): 86-99.

Marron, Rayyar. Humanitarian Rackets and their Moral Hazards: The Case of the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon. London: Routledge, 2016.

Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Offner, Francis. “150 Arab Orphans Will Be Repatriated from Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. October 4, 1949.

“Palestine Report.” The Palestine Post. May 5, 1948.

Peteet, Julie. Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

“Refugees Plan Hunger Strike.” Arizona Republic. July 1, 1959.

Sayigh, Rosemary. “Palestinian Camp Women as Tellers of History.” Journal of Palestine Studies 27, no. 2 (1998): 42-58.

Sayigh, Rosemary. “The Palestinian Identity Among Camp Residents.” Journal of Palestine Studies 6, no. 3 (1977): 3-22.

Sayigh, Rosemary. Too Many Enemies: The Palestinian Experience in Lebanon. Baghdad: Al Mashriq, 2015.

Schiff, Benjamin N. Refugees unto the Third Generation: UN Aid to Palestinians. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

Schiocchet, Leonardo. Living in Refuge: Ritualization and Religiosity in a Christian and a Muslim Palestinian Refugee Camp in Lebanon. Bielefeld: Verlag, 2022.

Truman, Harry S. Coll 54/1(S) ‘Middle East (Official) Committee: Reconstruction, 1949. British Library: London.

United Nations. Coll 54/1A(S) ‘Middle East (Official) Committee: Reconstruction, 1950. United Nations Library & Archives: Geneva.

“20,000 Arabs Flee to Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. April 18, 1948.

Zakarian, John. “Refugees Suffer Most.” The Edwardsville Intelligencer. June 15, 1967.

-

Diana Allan, Voices of the Nakba: A Living History of Palestine (London: Pluto Press, 2021), 272. ↑

-

Ibid., 273-274. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 186-188. ↑

-

Denzi Kandiyoti, Gendering the Middle East: Emerging Perspectives (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1996) 146-148. Includes vital interpretations about the paradoxical elements that encompassed communal activities of Palestinians following their 1949 displacement. Julie Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair: Palestinian Refugee Camps (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 6-16. Other works such as this use the idea of a Palestinian collective memory and identity to build its foundation. ↑

-

Rosemary Sayigh, Too Many Enemies: The Palestinian Experience in Lebanon (Al Mashriq, 2015), 5-11. Sayigh’s examination of specific refugee camps and how they were treated differently by the Lebanese Government led me to research Lebanon’s religious policies. Leonardo Schiocchet, Living in Refuge: Ritualization and Religiosity in a Christian and a Muslim Palestinian Refugee Camp in Lebanon (Bielefeld: Verlag, 2022), 12-15. This book built off Sayigh’s methodology and further influenced my focus on Lebanon’s refugee policies that targeted religious affiliations. ↑

-

William Cleveland and Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East. (New York: Routledge, 2016), 250-251. ↑

-

Cleveland and Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, 251-255. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 54. ↑

-

Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge University Press, 2004), 133-134. ↑

-

“Palestine Report.” The Palestine Post. May 5, 1948. ↑

-

“Lebanon Denies Invasion.” The Palestine Post. May 6, 1948. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 219-220. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 45-56. ↑

-

Rayyar Marron, Humanitarian Rackets and their Moral Hazards: The Case of the Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon (London: Routledge, 2016), 31-33. ↑

-

Rosemary Sayigh, “The Palestinian Identity Among Camp Residents.” Journal of Palestine Studies 6, no. 3 (1977): 7-9. ↑

-

Cleveland and Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, 339-340. ↑

-

Rosemary Sayigh, “Palestinian Camp Women as Tellers of History.” Journal of Palestine Studies 27, no. 2 (1998): 46. ↑

-

Sayigh, “Palestinian Camp Women as Tellers of History,” 49-50. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 261-265. ↑

-

Sayigh, “Palestinian Camp Women as Tellers of History,” 49-53. ↑

-

Kandiyoti, Gendering the Middle East, 146-148. ↑

-

Shay Hazkani, Dear Palestine: A Social History of the 1948 War (Stanford University Press, 2021), 185-186. Bracketed words inserted by original author. ↑

-

Government of Oman. File 11/32 IV Palestinian Arab Students as teachers for Muscat Govt., 1950. British Library: London. ↑

-

United Nations. Coll 54/1A(S) ‘Middle East (Official) Committee: Reconstruction, 1950. United Nations Library & Archives: Geneva. ↑

-

Cleveland and Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, 318-320. ↑

-

Hazkani, Dear Palestine, 185-186. ↑

-

Anna C. Bramwell, Refugees in the Age of Total War (London: Routledge, 2021), 277-278. ↑

-

Sayigh, “The Palestinian Identity Among Camp Residents,” 3-16. ↑

-

Harry S. Truman, Coll 54/1(S) ‘Middle East (Official) Committee: Reconstruction, 1949. British Library: London. ↑

-

Bramwell, Refugees in the Age of Total War, 261-262. ↑

-

Asher Kaufman, “Between Palestine and Lebanon: Seven Shi’i Villages as a Case Study of Boundaries, Identities, and Conflict.” The Middle East Journal 60, no. 4 (2006): 695. ↑

-

Allan, Voices of the Nakba, 294-296. ↑

-

Adel Manna, “The Palestinian Nakba and its Continuous Repercussions.” Israel Studies 18, no. 2 (2013): 95. ↑

-

Francis Offner, “150 Arab Orphans Will Be Repatriated from Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. October 4, 1949. ↑

-

“Arab Families to Come from Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. November 25, 1949. ↑

-

Philip Hochstein, “Pride and Prejudice in Mideast: Refugees Cost U.S. $350 Million.” The Philadelphia Inquirer. May 24, 1964. ↑

-

Cleveland and Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, 340-341. ↑

-

John Zakarian, “Refugees Suffer Most.” The Edwardsville Intelligencer. June 15, 1967. ↑

-

Peteet, Landscape of Hope and Despair, 9-20. ↑

-

“Crisis in Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. July 13, 1948. ↑

-

“Druze Fight in Lebanon.” The Palestine Post. July 7, 1949. ↑

-

“Lebanon Will ‘Do Her Duty’.” The Palestine Post. September 22, 1949. ↑

-

Benjamin N. Schiff, Refugees unto the Third Generation: UN Aid to Palestinians (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1995), 23-27. ↑

-

“Refugees Plan Hunger Strike.” Arizona Republic. July 1, 1959. ↑

-

Cleveland and Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East, 389-392. ↑