Mile High Hardcore: The Story of Denver’s Hardcore Punk Scene During the 1980s

By Daniel Harvey

On April 14, 1984, the underground venue Kennedy’s Warehouse at 2389 North Broadway in Denver hosted its last show with an all-local bill featuring Peace Core, Acid Ranch, Legion of Doom, and Immoral Attitude. This show marked the end of an era. At first it seemed no different than any other of Kennedy’s shows, but it was the end of yet another short-lived punk venue in Denver. After securing only yearly leases from Van Schaack Realty, even though a five-year lease was sought, Nancy Kennedy’s venue was closing. Tom “Headbanger,” who exclusively booked shows at the venue, recalled the situation, “It’s almost as if they had a plan to lease it out to someone else the whole time.” At night’s end, fights broke out and punks at the show began to tear down the building. This maelstrom of punk angst displayed the energy that the Denver hardcore scene possessed. It functioned as a metaphor for how the scene would be a revolving door.[1]

Kennedy’s Warehouse was a short-lived venue ran and financed by Nancy Kennedy with shows booked exclusively by Tom Headbanger. Its one year of operation was not easy going. From the start the venue faced financial issues and converting an old auto body shop into a functioning venue was not cheap. Expenses to keep the place heated, safe, and working prevented it from opening until the winter of 1983. Few patrons wanted to go to shows during the winter, so the venue quickly faced problems.[2] Operating as an all-ages venue and unable to draw a crowd during the week, Kennedy’s Warehouse eventually closed.[3] This was not the only venue to fall victim to an early departure as Denver’s hardcore punk scene continued to find it difficult to secure its footing during the 1980s.

Denver’s hardcore punk scene experienced its ups and downs much like any other in the nation. Although it found itself in a city that takes pride in its local arts and music, the hardcore punk scene and the underground at large were not generally accepted by city residents. Nonetheless, the Mile High City experienced a flourishing subculture that drew influence from around the country but struggled to create its own identity. Denver’s underground scene celebrated a DIY ethic manifest in a number of ways, including the production of fanzines, self-released albums, and non-traditional shows.

Various factors account for a thriving punk scene. Scenes owed their existence to the DIY ethic that played a constitutive role in resource mobilization and other organizational aspects of a social movement.[4] Politics was a part of punk. From 1983 through1984 scenes across the United States hosted a Rock Against Reagan festival in an effort to prevent his reelection.[5] While Denver did have its own thriving DIY scene and political ideology it was not enough to hold the scene together. This reveals an interesting difference between other successful hardcore scenes such as in New York City, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. Each of these urban scenes applied the DIY ethos to further their own scene and give it significance. This included record labels like L.A.’s SST Records, D.C.’s Dischord Records, and venues like New York’s CBGB. These entities gave hardcore punk bands the ability to record and spread the culture and fostered the overall popularity of hardcore. Not having a prominent venue or label, however, stunted the growth of hardcore in Denver.

Denver shared similarities with other major cities in its presence of violence. Steven Blush, Dewar MacLeod, and Johnathan Williams have found that violence was part of hardcore scenes. Violence created an uneasy perception of hardcore as outsiders perceived punks as “criminal, vicious, and dangerous.”[6] This perception rippled through the country, including in Denver, as violence tended to follow aggressive music.

As Denver is a city that celebrates local music, presumably hardcore could break out of its niche. This niche thrived but operated as a revolving door as many became jaded to punk. While the hardcore scene of the 1980s had its own marginal version of success, it did not realize its potential as a sustainable scene. To understand this in some detail, this article considers Denver’s location, unsustainability, and violence, and how they all impacted the hardcore scene that did not achieve its potential in the 1980s decade.

The New Scene

By the end of the 1970s, punk rock was already established in Denver, but something new was coming down the pipe. Hardcore punk is considered the more aggressive form of punk rock that “extended, mimicked, or reacted to Punk; it appropriated some aspects yet discarded others. It reaffirmed Punk attitude and rejected New Wave . . . for extreme kids.”[7] Both musicians and historians alike consider the California band Middle Class’s 1978 single “Out Of Vogue” the first hardcore release.[8] In Denver, Tom Headbanger was key to introducing this fresh new style of punk rock. The name “Headbanger” was one that he gave himself, being inspired by the Motörhead fan club name. His nickname came prior to metal fans being known as head bangers to the public.[9] Though he aspired to be a metal promoter, Headbanger found it hard to book metal bands cheaply, as he could not afford large production costs and bands needed financial guarantees. Having heard the Dead Kennedys’ 1981 single, “Nazi Punks Fuck Off,” Headbanger decided that punk was “heavier than metal, the culture was scrappier, and bands, conveniently, were willing to play for free or dirt cheap, because so few venues were booking them.”[10] With this being the case, the city’s hardcore punks were ready for their introduction to Denver’s music scene.

While there had been a pre-existing punk scene in Denver during the late 1970s, hardcore was new, different, exciting, and wild. Older punks were in their twenties or thirties and the scene was more alcohol-centric.[11] But what made the introduction of hardcore thrilling was the driving force of youth in the scene. Many young people (mostly teenagers) in the hardcore scene were disillusioned suburban kids who were attracted to punk through a number of avenues such as friends and co-workers, hearing classic punk bands like the Ramones, or visiting record stores like Wax Trax.[12] They helped hardcore grab hold in Denver and got kids into it. That said the change from classic punk to hardcore did not happen suddenly. Bands like Rok Tots helped bridge the gap between older style punk and the newfound hardcore scene as they were a part of both eras.[13] Rok Tots worked in both scenes, being older figures, while bringing the edge that hardcore required in Denver.

Rok Tots was the bridge, but local promoters like Tom Headbanger and Jill Razer, and allies like Nancy Kennedy, the scene’s beloved “den mother” of sorts (she was one of the few parents who would let hardcore kids stay at her house), also helped establish hardcore in Denver.[14] Kennedy started Kennedy’s Warehouse as a place for her son Tom (guitarist of Child Abuse) and other young people to play music. Duane Davis was another essential ally to the scene, as he is the owner of Wax Trax and ran Local Anesthetic. These individuals, along with bands such as Frantix, became some of Denver’s prominent figures of the era. They were further aided by the adoption of a DIY mindset.

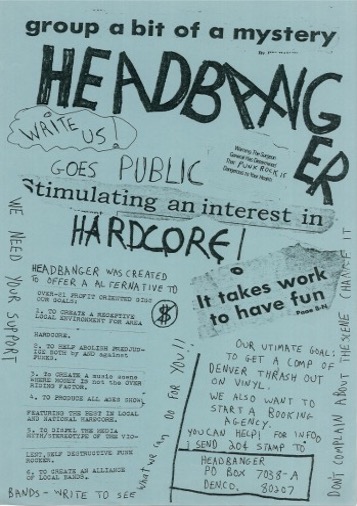

Denver’s DIY ethos helped the underground get its footing. An essential aspect of the scene was self-published fanzines. Fanzines were essential for many scenes in the late twentieth century, as many worldwide enjoyed them. Nationally, ‘zines were essential for spreading news, politics, art, poetry, where to find group gatherings, etc.[15] Headbanger made two short-lived fanzines: Rocky Mountain Fuse and My Degeneration. Fuse was a play on the Rocky Mountain News which Headbanger had been fired from.[16] Both of these fanzines covered local bands, shows, and also did reviews. There were other zines in Denver such as Local Anesthetic (also a record label) that covered much of the same content. In Denver, zines could either be traded or bought through the mail or at stores like Wax Trax in Capitol Hill. Zines also allowed scenesters to be more tapped into which local bands to support and shows that were taking place. These shows happened in warehouses, basements, football field gates, the Capitol lawn, and junkyards.

The junkyard shows were some of Headbanger’s most memorable. In 1985 Headbanger could not find a venue for German quintet Einstürzende Neubauten (“Collapsing New Buildings”), so he hosted it in a junkyard.[17] The band was notorious for their use of junk in their performances and Headbanger thought that the junkyard, while an odd place, would work as the perfect venue for the group. He designed tickets from animal bones that he spray-painted black. He produced and sold 100 tickets for the event.[18] There were not many shows held at the junkyard, but they did express that the DIY spirit was alive and well in Denver.

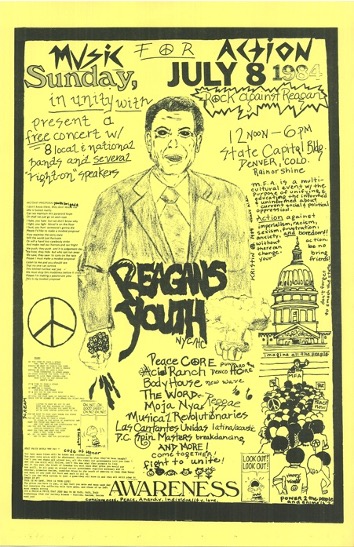

Another interesting show was 1984’s Music for Action. Music for Action was Denver’s version of Rock Against Reagan, and featured bands such as Reagans Youth (New York), Peace Core, and Acid Ranch.

Credit: trashistruth.com (1984 Fliers).

Music for Action was intended to be a Rock Against Reagan concert, but the promoters did not trust the Rock Against Reagan team and suspected that they would not arrive on time, so the name was changed. The Rock Against Reagan team was in fact late to the show that day.[19] Overall, what these types of shows displayed was the energetic drive of the underground, and the DIY ethos celebrated by local scenesters.

With the introduction of hardcore came the classic punk rock look. This style included mohawks, leather jackets, ripped pants, etc. In the beginning of the hardcore scene, if two people did not know each other yet looked similar, they were more likely to become friends.[20] Interestingly, Headbanger thought that since Coloradans value the outdoors so much, they would sport a different uniform of flannels and hiking boots, not the stereotypical punk look.[21] Headbanger thought this would be the case with Denver’s geographic location, but the influence from outside scenes dictated the style that Denver punks displayed. Adopting this proposed “uniform” might have helped in making it less easy to separate the punks from the non-punks and avoid ostracism by those outside the scene. That said, the adopted uniform from outside scenes helped establish a sense of community and oneness that allowed Denver punks to connect. Unlike with dress, isolation and geography shaped the Denver scene by impacting how booking agents booked shows and bands planned tours.

The Island Effect

Denver’s location created a sense of isolation for its music scene. Denver is often called an island or, as John Menchaca states, it’s an “area of nothingness that isn’t quite the West or the Midwest, and most certainly isn’t either of the coasts.”[22] To some, the term “island” is meant in an endearing manner as they love the isolation, while others like Headbanger think this created a more difficult situation for sustaining the scene. Geographical distance made it difficult to bring bands in initially. It was even more of an issue for Denver bands that wanted to tour as it was anywhere from eight to twelve hours away by car from the nearest major market. This made it difficult for bands trying to tour. By only offering one major city in the region, many touring acts would skip Denver entirely, opting instead to move closer to the California market.[23] Bands did not want to stop in Denver because they knew that they would make less money playing in a smaller market. Dead Kennedys on the other hand, would frequently play in Denver. Jello Biafra (lead singer of Dead Kennedys) was born in Boulder, Colorado, recognized the importance of playing in the Mile High City.[24] However, many touring bands that played in the city typically did so on weekdays, which caused frustration for fans.[25] Playing during the week in Denver meant that these bands could go to Texas or California and make more money in a larger scene. This did not necessarily mean that all bands skipped Denver, as many popular hardcore and punk bands like Black Flag, The Clash, and The Ramones did play shows put on by Feyline, a professional artist management and concert promotions company. Smaller promoters like Headbanger still got larger bands such as Misfits, Suicidal Tendencies, and Discharge to play their shows but getting people to come was not necessarily easy.

Pulling in bigger bands from other scenes was rewarding for smaller promoters like Headbanger. These shows were important because bringing in larger bands would typically draw a larger crowd and help pay for future shows that he would lose money on. Unfortunately, due to competition with other promoters who were not necessarily promoting for a living or were friends with an out-of-town band, promoters like Headbanger would not make money themselves.[26] However, having connections to other scenes was beneficial. For some promoters, like Bob Rob Medina, they would call bands through ads posted in magazines, and express why they wanted the bands to come to Denver.[27] Soon, other promoters came in from outside of Denver trying to bank on the new bustling scene. These outside promoters received the sobriquet “carpetbaggers” by Headbanger. An example of a “carpetbagger” group was Front Range Assault that relocated from San Francisco to move in on the local scene. Unfortunately for them, they did not find much success in Denver and stopped trying to promote shows after only one year.[28] This displayed the difficulty of booking shows at the time. Luckily over time, such hard work by local promoters was not needed to draw bands to the scene. Though that change had occurred, there were still issues that plagued Denver’s scene.

Unsustainability

Bands from other cities began to come to Denver but the issue of retaining spots for them to play was another matter. Many venues in the city were not welcoming of hardcore and would not host the shows. This left promoters in a predicament. They would go on to opt to have bands play in non-traditional venues like the aforementioned warehouses, basements, and other miscellaneous spaces. For the legitimate venues, it was not necessarily easy to operate either. If they were willing to host the shows, there were often concerns of hosting all-ages events. An abundance of young scenesters created a problem as they could not be in bars. Some venues were 3.2 bars, which allowed eighteen-year-old teenagers to come into the bars and drink lower grade beer. Actual all-ages shows did happen at these venues, but Headbanger stated that underage people were required to be “physically separated and there had to be a licensed police officer on site to enforce the separation,” which made hosting these shows harder.[29] Venues that did not operate as bars were more accessible for underage kids to attend but found it harder to turn a profit. Lack of profit and of a large market proved difficult for these venues.

One venue that struggled in Denver was Kennedy’s Warehouse. Kennedy’s was an all-ages venue that operated for a brief one-year stint from 1983-1984. It suffered a similar fate as others in Denver, as many venues were unable to keep their doors open for long.[30] Kennedy’s Warehouse opened initially as a space for Nancy Kennedy’s son and other local kids to have their own space to play music, but Kennedy’s faced issues from the word go. The city shut down the venue before it even opened, stating that they needed an occupancy license. This would not be the last issue; the building itself had to be brought up to code. Codes that needed to be met included covering brick walls with 7/8” sheetrock, covering all steel beams with drywall to avoid collapse, adequate plumbing, and eliminating the building’s space heater. Because of all of these issues, the venue did not open for six months.[31] By the time Kennedy’s Warehouse opened, it was winter. Nancy had to rent propane heaters to heat the place, which added another cost. Along with this, pipes would burst, and bands would not tour through as often. When the doors finally opened, it was hard to attract people to come to shows because it was too cold out. Once open, Kennedy’s had frequent shows, but it was hard to get kids to go because according to Headbanger, “they didn’t want to go every fucking night.”[32] Without getting people to go regularly, the price of operation was too costly. By the end, their leasing agent would not allow them to renew their lease and they closed their doors after their final show on April 14, 1984 (See Figure 2). The show featured all locals and ended in attendees tearing the place apart. Booking and promoting continued to be difficult in Denver after Kennedy’s Warehouse closed. It and other entities of Denver hardcore were affected similarly.

Featuring epitaphs of aspects of the scene that many disliked, including Nazis, positive punks, posers, and rock stars. This flier would also function as Kennedy’s epitaph as this would be the final show held there. Also, the flier states that people should boycott the St. Louis band White Pride’s upcoming show on May 5, 1984 at Packinghouse. Flier by Tom Headbanger.

Credit: trashistruth.com (1984 Fliers).

Bands, venues, and record labels that were widely celebrated and supported in Denver’s underground did not last long due to either a lack of agenda or planning. Many bands, for example, did not have a sense of direction when becoming a band other than wanting to play shows. This attitude mirrors the punk rock ethos of being anti-commercial and anti-mainstream, and by not wanting to achieve stardom. This ideology was not exclusive to Denver, as Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Dischord Records stated, “Our appearance was so offensive to people that it made us realize how disgusting the mainstream was, and we were glad to be outside of it.”[33] Some Denver punks practiced being anti-mainstream through their dress, as many would wear mismatched thrift store clothes along with the punk uniform, as was the case with the band Anti-Scrunti Faction (ASF) from Boulder.[34]

While punk is inherently anti-commercial, anti-mainstream, and anti-establishment, other limitations played a major role in the scene’s lack of growth. There were a few small, locally run record labels in Denver, but none stayed in operation long enough to support the local scene. During the 1980s there was Local Anesthetic, a label operated by Duane Davis. Local Anesthetic was short lived, releasing local albums from 1981 to 1985. These included releases from Bum Kon, Your Funeral, and Frantix, whose 1983 EP “My Dad’s a Fuckin’ Alcoholic” was an essential release of the scene due to its impact on and representation of Denver Hardcore punk (it has since been repressed by Jello Biafra’s record label Alternative Tentacles). Headbanger speculated that Local Anesthetic and others failed because they did not release a local compilation of all the local hardcore bands.[35]

Donut Crew Records of Boulder later released three “Colorado Krew” compilations, which represented the local bands of the scene from 1988-1990. Bands and labels alike found it difficult to get their records pressed to vinyl. Such difficulties were experienced by Your Funeral, whose 1982 “Evil Music” was rejected by a vinyl pressing plant in Wyoming for being too “disturbing.”[36] Many bands like the Lepers, Happy World, and Dead Silence self-released their records, but none of them were picked up by labels or recognized outside of Denver.[37] There were no long running labels in Denver that supported hardcore, and there was no money running through the punk scene to support a label or the hardcore artists. Most bands were not fortunate enough to record their songs. They could not afford the price of studio time given the lack of cheap recording studios in the city and were unable to release music. As a result, several bands are remembered through the fliers they are printed on and the memories of surviving scenesters. This lack of funds made it hard for musicians to not only support themselves as artists, but to preserve their legacy as Denver hardcore bands. Lack of a financial backing in the hardcore scene created long-lasting issues, but other major conflicts would drive punks away from the Denver scene.

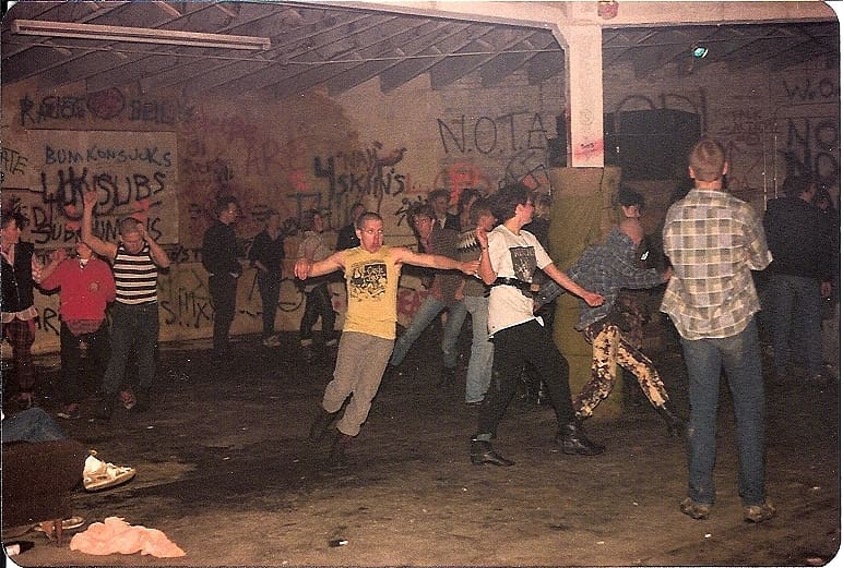

Violence and Internal Conflict

Generally, hardcore punk harbored a more aggressive following due to the nature of the music. The Mile High City was no exception. While not unique to Denver, hardcore violence is typically associated with punk or other aggressive music. Much of this violence is displayed at concerts. Slam dancing (a form of dancing where crowd members deliberately collide into each other) became popular and was prominent in the scene. This was not necessarily well liked, as some did not welcome getting slammed into really hard while slam dancing. This was not their only worry, as many began to take it past the point of slam dancing and began intentionally harming other people at the shows. There are members of the 1980s scene who have said that violence played a large part in their falling out with punk, and it is why they stopped participating.[38] Interestingly though, according to Headbanger, they did not actually do anything to stop the violence. These members of the scene were called “Positive Punks.”

States: “Don’t complain about the scene change it.” Many positive punks of the era would complain about the violence at shows instead of taking on the issue head on.

Credit: Trashistruth.com (1983 Fliers).

They were concentrated in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Denver.[39]At shows, Headbanger passed out questionnaires that asked what peoples’ “gig gripes” were with the scene. Of the forty individuals that responded to the survey, half of them stated that they wished that there could be something done about the violence at shows.[40] This came as no surprise to Headbanger, as he had previously stated, “don’t complain about the scene; change it.” In a separate article, he opined that if the twenty people who were complaining about the five people causing problems actually did something about what they were complaining about, they would see results.[41] With Denver’s scene being modest, it was harder for members of the scene to control violence at shows (especially when nobody stepped in to stop it) whereas other cities such as D.C. were successful in doing so. If more had stepped in to actively stop violence in Denver, fewer members of the scene would have left, and there could have been more substantial growth that was similar to other major cities. This idea was easier said than done in Denver.

Denver’s underground lacked policing. This meant that individuals were not stepping up to protect others from being injured at shows. Occasionally, however, there would be police officers at the shows. Unlike other scenes though, Denver’s punks did not experience a large amount of police violence or brutality. Police shut down events or venues at times, such as when they closed down the GAGA Club in 1983.[42] In most cases, the police did not intervene with the scene. Headbanger recalled that he could not “remember a time where a cop beat anybody up for being punk in Denver. The only time someone got beat up was if they gave cops an attitude.”[43] Denver’s relationship with cops varied from other scenes like Los Angeles, where police would frequently break up shows and beat up attendees for simply being there. Henry Rollins, lead singer of Black Flag, said that police would, “put guns in your face” and that Los Angeles punks were “scared of cops.” Doing this and the police’s tendency to “practice riot control” were common examples of extreme force that were carried out in Los Angeles in 1981.[44] This violence would continue in the Los Angeles scene well into the mid-1980s. In Denver, hardcore punks’ less antagonistic relationship with police would continue.

Venues at bars periodically used Denver police officers for security. This typically happened because some venues required a police officer for the show to go on or to separate young kids from the drinking area at an all-ages bar show. Promoters both then and now agree that nobody in their right mind would use a cop if it were up to them.[45] The police were also used to stop people from doing drugs. Typically, cops were more confused by slam dancing, but did not see it necessary to harm any of the concertgoers for having a good time (see Figure 4).

Outside sources contributed to issues within the scene but were not the biggest source of violence. While punks were bothered for their appearance and were attacked or called derogatory names such as “faggots,” people bothering them were not a part of the scene.[46] Name-calling and harassment was common for Boulder punks (especially women), as fraternity members at the University of Colorado were often the most troublesome.[47] These external factors were not the worst violence or harassment that Denver punks faced. Many scenesters claimed that fellow punks were the primary source of violence at shows.[48]

One group in particular that went to shows with the intention of harming people was the skinheads or “skins.” The skinhead movement originated in England during the 1960s. It was sparked by social alienation and strived for solidarity for members of the working class. Though originally apolitical; the movement attracted those who were extreme nationalists, far-right violent racists and neo-Nazis.

Photo two shows punks dancing to the band ASF.

Credit: Duane Davis.

In many scenes, including Denver, there was not an abundance of skins at first. That would change as national zines began covering skins. There came skinhead resurgence by the mid-1980s where many punks emulated what they read or saw, became skins themselves, and caused violence in the scene.[49] Skins in Denver were not just coming to shows to single out people of color or other minority groups. Some scene members, like Nate Butler, felt that it was especially difficult to be openly homosexual in the scene. It became even more difficult upon the skins’ arrival.[50] Denver skinheads were well known for coming to shows to mess things up for everyone else and to harm people. Skinheads behaved like this in other cities, such as New York; as Harley Flanagan observes that skins were, “less about fashion and ‘dancing’ and more about street fighting and just being hooligans.[51] Although Headbanger and many others were friends with skins in the scene, he took issue with them because they were, “hurting people that were in the same community as them and people that they identified with.”[52] That said, skins were not the only instigators of conflict in the scene.

Cliques also presented issues in Denver. These cliques or “factions” were typically represented by which part of town the scenesters were from, or what high school they went to. Prior to the factions dictating relationships in the scene, many bonded because they were hardcore punk rockers. Other rifts existed in the scene. The band Anti-Scrunti Faction (ASF) was an all-female punk band from Boulder that typically bullied the “non-punk” girls or “Scrunti” of the scene. These “Scrunti” were typically girls that dated members of a band and would only participate in the scene as long as they were dating that member. Headbanger also stated that some were just as afraid of them as they were the skins.[53] To others like Dean/Don Lipke and the Kenosha Punks, the “Scrunti” were described as “good looking and accessible.”[54] Other types of bullying occurred in the scene for those that did not look a certain way or were new members to the scene. These people were typically labeled as posers, but they would eventually be accepted into the scene if they stuck around long enough. Being in the scene long enough gave members the right to label other newcomers as posers.[55] This continued as many people left and new kids joined the underground.

Many left the scene due to violence, and so too would Headbanger. While at one of his shows on November 15, 1984 at Packinghouse, he tried to break up a fight and was beaten up so badly that he booked shows less frequently and eventually stopped while other promoters like Jill Razer went on to be one of the more prominent promoters in the scene.[56] Headbanger’s exit from the scene was a common occurrence as many others would eventually move on from punk. Some of his pursuits after his punk rock tenure included touring with Psychic TV, starting Denver’s chapter of Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (TOPY), and eventually moving out of Colorado.

Conclusion

While the 1980s scene was an exciting and dynamic time filled with pulsating energy, Denver’s hardcore punk scene would not make or leave as large of an impact as it did in other major cities during the 1980s. Due to Denver’s location, unsustainability, internal strife, and violence, the hardcore scene was never truly able to reach its full potential as a thriving and successful scene in the Mile High City. Denver was an unsuitable host for the growing hardcore scene compared to D.C., New York City, and Los Angeles. That being said, a foundation for future generations remained to learn from so as to not repeat the mistakes that happened in the 1980s. Hardcore and punk operated as a revolving door giving outlet and expression to be angry about something. And, undeniably there will always be a young and excited audience that wants to keep the exhilarating energy alive and flowing.

As the antithesis to over-produced mainstream rock bands of the late 1960s, the 1970s, and 1980s, as well as rock bands known for their complicated musical techniques and cerebral compositions, hardcore punk took its hold as underground culture and music. The hardcore punk movement sprouted a network of local bands in Denver and across the United States. Raw, minimalist, spontaneous, expressive, and aggressive, hardcore was more accessible to teens as it was basic and relatable and seemed as though anyone could pick up an instrument and form a band. Harmonically minimal, hardcore punk was fast, loud, and hard. It was rock that displayed an aggressive attitude. Hardcore was its own thing. It gave expression to alienated youth. The 1980s provided the catalyst for the fury and dissent of hardcore. It was a decade marked by rapid change that was reflected by growing unrest and teen angst. Youth wanted to see change in their environment through the musical equivalent of a punch in the face.

As for Headbanger, he and many others have moved on from Denver’s hardcore scene, which still lives through other entities. Wax Trax continues to sell records to fans eager to discover new music. Labels like Donut Crew Records are now defunct, but others such as Convulse Records offer a collection of Denver bands. Adam Croft started Convulse to preserve the history of Denver’s current hardcore scene by supporting bands such as Goon, Faim, and Product Lust.[57] There are now many functioning DIY spaces for hardcore to continue to thrive, namely Seventh Circle Music Collective.[58] When hosting shows, both Croft and Aaron Saye, the founder of Seventh Circle Music Collective, claim that the scene now polices itself much better than the 1980s hardcore scene had. With these road guards in place, hardcore punk in the Mile High City lives on.

Notes

[1] Tom “Headbanger”, Interview by Daniel Harvey, March 10, 2020, Interview 2.

[2] Headbanger.

[3] Headbanger.

[4] Michael James Roberts and Ryan Moore, “Peace Punks and Punks Against Racism: Resource Mobilization and Frame Construction in the Punk Movement,” Music and Arts in Action 2, no. 1 (San Diego: San Diego State University Press, March 29, 2009), 5.

[5] Jonathan Kyle Williams, “‘Rock Against Reagan’: The Punk Movement, Cultural Hegemony, and Reaganism in the Eighties,” Master’s Thesis (Cedar Falls: University of Northern Iowa Press, 2016), 26.

[6] Dewar MacLeod, Kids of the Black Hole: Punk Rock Postsuburban California (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 112.

[7] Steven Blush and George Petros, American Hardcore: A Tribal History (Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House, 2010), 15. Definitions: Punk Rock: a loud, fast-moving, and aggressive form of rock music, popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s. New Wave: a style of rock music popular in the 1970s and 1980s, deriving from punk but generally more pop in sound and less aggressive in performance.

[8] Blush and Petros, 19.

[9] Tom Headbanger, Interview by Daniel Harvey, April 29, 2020, Interview 5.

[10] Kyle Harris, “Headbanger’s Ball: Tom Banger Remembers Early Denver Punk,” Westword, August 6, 2019.

[11] Tom Headbanger, Interview by Daniel Harvey, March 21, 2020, Interview 3.

[12] Robert Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks: Stories from the ’80s Denver Punk Scene (Robot Enemy Publications), 68-69, 84, 89, and 109. Bob Rob Medina’s personal introduction to hardcore mentioned in Interview by Daniel Harvey March 13, 2020.

[13] Bob Rob Medina, Interview by Daniel Harvey, March 13, 2020.

[14] Tom Headbanger, Interview 4, April 5, 2020.

[15] SaraMarcus, Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution (NewYork, HarperCollinsPublishers, 2010), see pages 17, 59, and 225. This text offers fanzines from the Olympia, Washington and Washington D.C. Riot Grrrl scenes. A brief history of fanzines is offered in Teal Triggs, “Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic.” Denver’s Zine Library also offers large fanzine collection.

[16] Tom Headbanger, Interview 1, March 5, 2020.

[17] Michael Small, “When A Wild German Quintet Turns Rubble Into Rock, The Sound Is Simply Smashing” (People Magazine, June 10, 1985), 64-66.

[18] Tom Headbanger, Interview by Daniel Harvey, March 5, 2020, Interview 1.

[19] “Reagan Youth, Peace Core & Acid Ranch,” accessed May 11, 2020; Tom Headbanger Interview 1, March 5, 2020.

[20] Tom Headbanger, Interview 1, March 5, 2020.

[21] Headbanger.

[22] John Menchaca, “Why A Changing Denver Is Creating A Hotbed For Hardcore In 2019”.

[23] Tom Headbanger Interview 1, March 5, 2020.

[24] Blush, American Hardcore, 315.

[25] Tom Headbanger, Hallewell Survey, 1982, file 96, box 2, Tom Hallewell Papers, The Denver Public Library’s Western History/Genealogy Department.

[26] Tom Headbanger Interview 3, March 21, 2020.

[27] Bob Rob Medina Interview, March 13, 2020.

[28] Tom Headbanger Interview 3, March 21, 2020.

[29] Tom Headbanger Interview 1, March 5, 2020.

[30] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 214-16.

[31] Medina 171-77.

[32] Tom Headbanger Interview 3, March 21, 2020.

[33] Blush, American Hardcore, 63.

[34] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks,112.

[35] Tom Headbanger Interview 4, April 5, 2020.

[36] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 54.

[37] Tom Headbanger Interview 4, April 5, 2020.

[38] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, many accounts throughout the text, examples on pages: 99, 104, 106, 114-15, 117, 158-60.

[39] Tom Headbanger Interview 2, March 10, 2020.

[40] Tom Headbanger, Survey, 1982, file 96, box 2.

[41] Tom Headbanger Hallewell, Declaration, 1982, file 36, box 1, Tom Hallewell Papers, The Denver Public Library’s Western History/Genealogy Department.

[42] “More . . . Local Hardcore.” Accessed May 11, 2020. http://www.trashistruth.com/pages/1983-05- 06a.htm.

[43] Tom Headbanger Interview 2, March 10, 2020

[44] Blush, American Hardcore, 41-43.

[45] Interviews with Aaron Saye April 7, 2020, Adam Croft February 25, 2020, and Tom Headbanger, March 10, 2020.

[46] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 113 and129.

[47] Medina, Bob Rob. “Anti-Scrunti Faction (A.S.F.) Part 2: A Chat with Sarah.” March 18, 2015.

[48] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 42, 104, 115 and 158.

[49] Blush, American Hardcore, 34.

[50] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 75

[51] Harley Flanagan, Hard-Core: Life of My Own (Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House, 2016), 149.

[52] Tom Headbanger Interview 2, March 10, 2020.

[53] Headbanger.

[54] Medina, Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks, 116.

[55] Bob Rob Medina, Interview, March 13, 2020.

[56] Tom Headbanger Interview 5, April 29, 2020.

[57] Adam Croft, Interview, February 25, 2020.

[58] Aaron Saye, Interview, April 7, 2020.

Bibliography

Blush, Steven, and George Petros. 2010. American Hardcore: A Tribal History. Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House.

Croft, Adam, interview by Daniel Harvey, February 25, 2020.

Flanagan, Harley. 2016. Hard-Core: Life of My Own. Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House.

Hallewell, Tom “Headbanger”, declaration, 1982, file 36, box 1, Tom Hallewell Papers, The Denver Public Library’s Western History/Genealogy Department.

Hallewell, Tom “Headbanger”, fanzine, 1982, file 96, box 2, Tom Hallewell Papers, The Denver Public Library’s Western History/Genealogy Department.

Harris, Kyle. 2019. “Headbanger’s Ball: Tom Banger Remembers Early Denver Punk.”

Westword. August 6, 2019. https://www.westword.com/arts/tom-banger-remembers-early-denver-punk-and-thee-temple-of-psychick-youth-11437933.

“Headbanger.” n.d. Accessed April 20, 2020.http://www.trashistruth.com/pages/1983-12_hb2.htm.

Headbanger, Tom, interview by Daniel Harvey, March 5, 2020, interview 1.

Headbanger, Tom, interview by Daniel Harvey, March 10, 2020, interview 2.

Headbanger, Tom, interview by Daniel Harvey, March 21, 2020, interview 3.

Headbanger, Tom, interview by Daniel Harvey, April 5, 2020, interview 4.

Headbanger, Tom, interview by Daniel Harvey, April 29, 2020, interview 5.

“Local Hardcore.” n.d. Accessed April 20, 2020. http://www.trashistruth.com/pages/1984-04-14c.htm.

MacLeod, Dewar. 2012. Kids of the Black Hole: Punk Rock Postsuburban California. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Marcus, Sara. 2010. Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

Medina, Bob Rob. “Anti-Scrunti Faction (A.S.F.) Part 2: A Chat with Sarah.” March 18, 2015. http://www.punkerbob.com/2015/03/anti-scrunti-faction-asf-part-2-chat.html.

Medina, Bob Rob, interview by Daniel Harvey, March 13, 2020.

Medina, Robert. Denvoid and the Cowtown Punks: A Collection of Stories from the 80s Denver Punk Scene. United States: Robot Enemy Publications, 2015.

Menchaca, John. n.d. “Why A Changing Denver Is Creating A Hotbed For Hardcore In 2019.” Accessed April 19, 2020. https://cvltnation.com/why-denver-is-changing-the-hardcore-game-2019/.

“More…Local Hardcore.” Accessed May 11, 2020. http://www.trashistruth.com/pages/1983-05-06a.htm.

“Reagan Youth, Peace Core & Acid Ranch.” Accessed May 11, 2020 http://www.trashistruth.com/pages/1984-07-08f.htm.

Roberts, Michael James, and Ryan Moore. 2009. “Peace Punks and Punks Against Racism: Resource Mobilization and Frame Construction in the Punk Movement.” Music and Arts in Action 2 (1): 21–36.

Saye, Aaron, interview by Daniel Harvey, April 7, 2020.

Small, Michael. “When A Wild German Quintet Turns Rubble Into Rock, The Sound Is Simply Smashing.” People, June 10, 1985.

Triggs, Teal. 2006. “Scissors and Glue: Punk Fanzines and the Creation of a DIY Aesthetic.”Journal of Design History 19 (1): 69–83.

Williams, Johnathan Kyle. 2016. “‘Rock against Reagan’: The Punk Movement, Cultural Hegemony, and Reaganism in the Eighties,” Master’s Thesis, University of Northern Illinois. 2016. Dissertation and Theses @ University of Northern Iowa, 239. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/239.