Back Channel Diplomacy: United States – Pakistan Covert Relations During the Soviet – Afghan War

By John Elstad

F-16 Fighting Falcons Stranded in the Desert

July 22, 1996 was a beautiful day to go flying. Six A6E Intruder aircraft departed from Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington, on their final mission for the United States Navy (USN). Veterans of three decades of aerial combat and deterrence for America, these aircraft were winging their way into retirement, destination Davis-Monthan Air Force Base (AFB) in Tucson, Arizona. Known affectionately as the “bone yard,” Davis-Monthan AFB is the high desert repository for thousands of retired military aircraft. It is here that airplanes no longer deemed adequate for military service are interned, put through a special preservation process, and parked in a spacious desert aircraft parking lot, where the dry air and infrequent rain leave them in a near state of suspended animation. From this point they await their eventual fate – resale to a foreign nation, transition to target drones, cannibalization for parts, nomination as a static display, or scrapping.

As the flight of Intruders approached Davis-Monthan AFB, the aircrew flying these veteran airframes could see acres of mothballed aircraft, row upon row of Cold War veterans: F-4 Phantoms, B-52s, A-7 Corsairs, C-123 Caribous, etc. The A-6s landed and taxied to the aircraft depot acceptance facility, the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG), located on the east side of the airfield. The aircraft were parked, shutdown, and maintenance logbooks handed over to AMARG personnel. The Intruders had officially concluded their naval service.

As this ritual was taking place, it was hard not to notice several rows of cocooned F-16 fighter aircraft parked adjacent to the AMARG depot facility. As a relatively new generation of fighters, they looked out of place when compared to the other retired war horses occupying the grounds. An interesting conversation ensued between the Intruder aircrew and AMARG personnel. It turns out these particular F-16s, also referred to as Vipers, were initially intended for delivery to Pakistan as part of a U.S. government Foreign Military Sales (FMS) transaction. AMARG personnel mentioned that the aircraft were actually brand new when flown to Davis-Monthan a few years earlier, with each airframe probably having less than ten hours of flight time. Their understanding was that Pakistan had violated an international arms agreement of some sort and that Washington subsequently refused to hand them over, essentially holding the aircraft hostage. The irony of the whole deal was that the Pakistanis had already paid for them![1]

Credit: Image downloaded from https://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article28.html.

United States and Pakistan – Marriage of Convenience

The saga of the stranded F-16s in the high desert of southern Arizona is indicative of the often contentious relationship between the United States and Pakistan since the latter’s founding in 1947. The interests of these two nations have sporadically intersected over the decades, and when necessary, they have ramped up diplomacy to suit each other’s needs. One such occasion transpired in December 1979, when Russian military units rolled into Afghanistan to spark the beginning of the decade long Soviet – Afghan conflict. The United States at the time was in the midst of the Cold War and out of this situation emerged a chance for the Americans to bog down the Soviets in their own version of Vietnam. By enabling Afghan Freedom fighters, known as the mujahideen, to effectively fight the invaders, the United States could cause harm to the Soviet Union without spilling American blood.

During the Soviet – Afghan war the United States supported the mujahideen rebels with military arms and other supplies. This aid was routed through Pakistan. To ensure that this flow continued uninterrupted, Washington agreed to provide the Pakistan government with economic and military assistance. One of the most sensitive issues was Pakistan’s urgent request for new and sophisticated weaponry, including F-16 fighter aircraft, to ensure supremacy over Pakistan’s principal antagonist – India.[2] Behind the tale of those F-16s sitting in the Arizona desert, there is an entire complex story of great power politics and regional rivalries.

This study will focus on the diplomacy and behind-the-scenes activities that supported the continued use of transportation routes through Pakistan by the United States, primarily the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Although there has been much written about the American involvement in support of the Afghan Freedom Fighters during this war, recently declassified documents, mainly originating from the U.S. intelligence services as a result of numerous Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) requests, tell of a more in-depth and complicated relationship between the United States and Pakistan.

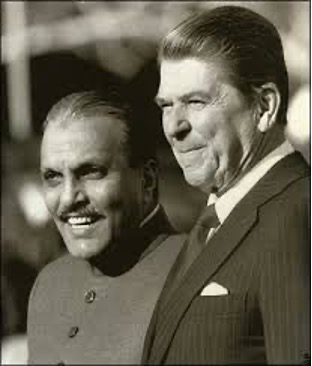

Scholarship on the subject of United States – South Asia diplomacy during the 1980s explores the decisions made between the United States and Pakistan with respect to the impact of support for the mujahideen. However, the “why” of these decisions was limited due to the sources and information available at the time. Dennis Kux, for example, in his 2001 book, The United States and Pakistan, 1947-2000, delves into several high-profile meetings between American President Ronald Reagan and Pakistani President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq. His analysis explains the result of these meetings; however, declassified CIA documents now provide insight to the in-depth preparation and strategy formulation conducted by Reagan and his advisors prior to these engagements.[3] The secret material and intelligence utilized by Reagan and his staffers was still classified at the time of Kux’s research for his book.

In a similar vein, A.Z. Hilali in his US-Pakistan Relationship: Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, published in 2005, mentions India’s negative reaction to the United States selling F-16s to Pakistan and explains the quantum leap in defensive capabilities the Vipers would provide to the Pakistan Air Force.[4] CIA documents examining this issue, which were not declassified until after the publication of his book; expand on India’s apprehension of the F-16 sale. With these materials now available, the direct relationship between the story of U.S. support for the mujahideen and that of the India-Pakistan rivalry can be reexamined.

At a rare moment in time and place, the American desire to battle the Soviet Union utilizing an Afghan proxy intersected with Pakistan’s quest to catch up to India in the South Asian nuclear arms race. This may be the most significant aspect of the relationship between Washington and Islamabad during this time of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development and brinksmanship. Although Pakistan’s government realized an outright request of support to develop a nuclear weapon was not possible, nonetheless other American military aid would free up resources to pursue that goal. Like two reluctant partners, Washington and Islamabad would play off each other’s desires to achieve their own national goals.

Credit: H.Z. Hilali. US-Pakistan Relationship: Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan. (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005).

The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and Support for the Mujahideen

Jimmy Carter occupied the White House when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979 to prop up the proxy communist government in Kabul against a growing insurgency. Carter and his advisors initially decided to counter the Soviet assault with public condemnation, economic sanctions in the form of a grain embargo, and eventually a boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. It was at this time the initial impetus for arming Afghan Freedom Fighters started. Initially these efforts were inadequately coordinated and lightly funded. Carter had conducted a less bellicose approach to foreign policy early in his presidential term.[5] This was about to change in a significant way. Ronald Reagan defeated Carter to become the 40th president in a landslide election in November of 1980. The spigot for numerous CIA covert operations around the world was set to open up to maximum capacity, and it included funding for military aid flowing to Afghanistan and Pakistan. Reagan had a more assertive agenda than did his predecessor with respect to waging the Cold War more aggressively. This was referred to as the “Reagan Doctrine.” Basically, this meant not settling for containing the expansion of communism, but rolling it back wherever the United States could bring its influence to bear.

The Islamic Republic of Pakistan also had reasons to support the mujahideen in their battle with the Soviet invaders. The countries shared a common border in Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP). If the Soviets defeated the Afghan insurgents, what would stop them from continuing their offensive and coming after Pakistan next? Soviet tanks could roll through the province of Baluchistan (Balochistan) coming into proximity of the Gulf of Oman. Also, with the seaside city of Karachi, Pakistan had something the Russians had been pining for since the time of the tsars: a warm water port with access to the Indian Ocean.[6]

Another reason for the Pakistan government, and President Zia in particular, to support the Afghans was the enhanced potential for a lucrative relationship with the United States. Zia was the leader of a poor country with a large population and limited natural resources. He saw the possibility for positive outcomes in an association with the Reagan administration and its desire to ally with Pakistan in support of the Afghan rebels. Zia could solidify his position as president by bringing in economic and military aid that would be popular with his constituency. Thus, he could achieve two objectives at once, making things better for himself and his country.[7]

Early on, the Government of Pakistan (GoP) levied an artificial limitation on support to the Afghan rebels by requiring all furnished military equipment to be of Soviet origin, including small arms like the AK-47 assault rifle. The CIA agreed to the arrangement as it would build the case of plausible deniability for Zia’s regime and the Reagan administration. Following combat between the Soviet Army and Afghan rebels, the detritus of war remaining on the battlefield would be Soviet-style weaponry, implying that the mujahideen were using captured Soviet arms to wage their war of resistance.[8] To support this effort the CIA turned to Egypt. Cairo had developed a cordial rapport with the United States following a decades’ long relationship with Moscow. The CIA procured Soviet made arms, plentiful in the Egyptian military, and sent them to Pakistan.[9]

In another effort to distance himself from potential Soviet accusations of collaboration, Zia attempted to minimize the American presence in Pakistan with respect to armaments and military supplies. As Chief of Army Staff Zia-ul-Haq rose to the top political position in his country as some leaders of newly emerging, post-colonial nations had, by a coup d’état. Forcing out President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Operation Fair Play, the code name for the coup in July 1977, and amid civil unrest, Zia assumed control of Pakistan with the support of the army.[10] To maintain power, he directed the Pakistan Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency, similar to the American CIA, to surveil potential political enemies, including members of the Pakistan Communist Party.[11] To lead the ISI, Zia appointed Akhtar Rahman Khan, a close confidant from his military days.[12]

As soon as arms shipments entered Pakistan territory, custody would be turned over to the ISI. Other than minimal support from a handful of CIA advisors, American involvement abated for a time. Hilali contends, “The CIA transported weapons to Pakistan, mostly by sea to the port of Karachi, and then the ISI loaded the cargo onto heavily guarded trains, which carried it to Islamabad, Peshawar, and the border town of Quetta. Peshawar, the provincial capital of Pakistan’s North West Frontier Province (NWFP), was the principal conduit for external weapons … the ISI established ‘more than 100 depots’ for weapons in Afghanistan and Pakistan and used ‘more than two hundred different routes’ to supply mujahideen groups.”[13]

Balancing Act

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Carter administration initially made overtures to Zia with respect to providing support to the mujahideen. Unfortunately, such efforts were hampered by Carter’s previous indifference to Pakistan. Consequently, Zia decided to wait until possibly a new administration was in place to move forward with his initiatives.[14] In January 1981, Reagan was sworn into office, and with Congressman Charlie Wilson (D-TX), an influential member of the House Defense Appropriations Committee leading the charge, covert action to furnish Afghan anticommunist resistance fighters with military equipment accelerated. Initially the goal of this effort was to try to kill as many Soviet personnel as possible. Thoughts of actually defeating the Soviets were deemed infeasible.[15] By late 1979, the Muslim guerillas were being referred to as mujahideen, or Freedom Fighters.[16] The Islamic Republic of Pakistan and western press grasped this moniker. Both used it for propaganda purposes. What better way to promote those fighting communist oppression, not only in Central and South Asia, but globally? The Arabic term was used liberally for the remainder of the Soviet-Afghan struggle.[17] Afghanistan’s mujahideen were exceptionally diverse. They arose out of local militias and were led by regional commanders or warlords who independently took up arms across Afghanistan to fight the Soviet Union. Mujahideen included ethnic Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Tajiks, and others. Some were Shi‘i Muslims sponsored by Iran, while most factions were made up of Sunni Muslims.

As the military endeavor was getting underway, the Reagan administration started to address how American activities would affect the overall geopolitical balance in South Asia, and correspondingly, the world stage. This was not going to be simply a matter of just supplying arms to the mujahideen; there were other political and diplomatic sensitivities on regional and global levels that needed attention. Islamabad, Kabul, Moscow, New Delhi, and Washington had interests affected by this undertaking. Consequently, diplomacy would be complicated.

The United States and the Soviet Union had been in a Cold War for several decades when the USSR invaded Afghanistan. The Soviet Army entered the country to prop up an Afghan communist puppet government led by Babrak Karmal, and to ensure communist influence was maintained in this vital region of South Asia.[18] Washington immediately protested and, eventually, saw this as an opportunity to use the Afghan rebels to fight a proxy war.

One of the easier aspects of the entire effort as it turned out was persuading the Afghan rebels to fight against the Soviet invaders. Despite the Soviet Army having an overwhelming superiority in weapons technology and professional training, the mujahideen were enthusiastic, almost fanatic, in their resistance. They would likely continue fighting with or without support from outside sources.

Pakistan was the linchpin to this situation. Located strategically between India on the east and Iran on the west, its location favored American interests with respect to access to Afghanistan. Iran would have been the best choice before 1979, but the United States had recently lost its key regional ally early that year when an Islamic Revolution overthrew the Imperial government of the Shah of Iran. Despite being small in geographical size and struggling economically, Pakistan held a strong hand and would excise a high price to those wanting access to the north. India also played into the script due to New Delhi’s antagonistic relationship with Islamabad. On good terms with the Soviet Union since Jawaharlal Nehru’s ascension to leadership as Prime Minister in 1947, New Delhi exhibited a strong independent streak. India had its problems, including trying to cope with one of the most densely populated societies in the world. Having crossed the nuclear threshold in 1974, India held a position of regional military power in South Asia; however, a complicated relationship with its neighbor to the west was constantly festering. If it was going to accomplish its goals in Afghanistan, the United States had to take India’s concerns into consideration, along with those of other nations in the region.

India and Pakistan

The Pakistan-India relationship was contentious. While the U.S. and the USSR had been at odds since the late 1940s, the Pakistanis and Indians were simultaneously conducting a cold war of their own. Pakistan was partitioned from India in 1947 during the dismantling of Britain’s overseas colonial empire. The process of the British relinquishing control and handing power over to the Pakistanis and Indians was messy. British authorities made controversial decisions about the partition seemingly without adequate input from the two provisional governments or their respective national leaders: Pakistan’s Muhammad Ali Jinnah and India’s Jawaharlal Nehru.[19] With the British departure, the two nations were in a state of conflict. With a predominate Muslim Pakistan and Hindu India, there was much friction over religious differences, including displaced populations of Muslims and Hindus who found themselves on the wrong side of the newly drawn borders. This hostility was punctuated by numerous military clashes, including three major wars, mainly over disputed territory in the Kashmir region.[20]

Islamabad had an unquenchable desire to develop a nuclear weapon. India had crossed the nuclear threshold on May 18, 1974 with the detonation of an atomic device on the Pokhran Test Range in northwestern Rajasthan Province. The Pakistanis pursued their own nuclear weapons development in response, fearing potential “nuclear blackmail” by their neighbor. When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, Pakistan’s nuclear ambitions had not yet come to fruition, but India and the rest of the world knew, or had strong suspicions, that Islamabad was trying hard to achieve nuclear weapons status.

Moreover, the United States had responsibility as a world power to adhere to the growing international pressure against the use and proliferation of nuclear weapons. The 1970s and 1980s saw a groundswell throughout the world, especially in Western Europe, of limiting, and in some areas, abolishing nuclear weapons. Agreements such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act (NNPA) were in place. Further, the international community expected the leading world powers, namely the United States and the Soviet Union, to abide by their provisions. The NPT, for example, declared, “The NPT non-nuclear weapons states agree never to acquire nuclear weapons and . . . agree in exchange to share the benefits of peaceful nuclear technology and to pursue nuclear disarmament aimed at the ultimate elimination of their nuclear arsenals.”[21] The NPT was ratified on March 5, 1970, with 188 nations signing on. Five nations, however, refused to sign, including Pakistan and India.[22]

Pakistan Nuclear Weapons Development and F-16s

In order to get aid to Afghanistan the United States had to go through Pakistan. This would not be easy. Islamabad held a strong hand and would drive a hard bargain, especially with a country as wealthy as the United States. Zia strived to attain superior conventional arms transfers to gain a military advantage over India. At the top of the wish list were F-16 fighter aircraft. Underlying negotiations for aid and assistance would be an unspoken truth. This was the contentious issue whenever Washington and Islamabad discussed proposals for arms sales. The U.S. Congress, which had oversight authority on security assistance and bilateral agreements involving arms transfers, was paying attention. With initiatives on nuclear non-proliferation, the United States would not countenance Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program.[23]

One of the more controversial aspects of both the F-16s and Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development was the issue of nuclear weapons delivery. Although India had detonated its first nuclear device in 1974, as of the early 1980s India’s military had not yet pursued production of a nuclear weapons stockpile nor developed a weapons delivery platform for an atomic weapon. India’s ballistic missile development program was in its infancy, and a viable nuclear warhead tipped ballistic missile capable of targeting Pakistan would not come to fruition for at least another decade. But the Indians knew the F-16s that Washington had recently sold to the European countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) were capable of delivering nuclear weapons.[24] With the Pakistanis hard at work seeking to fulfill their own nuclear ambitions, the combination of an F-16 delivery capability mated with a nuclear warhead would put India in an untenable position. All these factors would have to be considered as part of the delicate balancing act the Reagan administration would have to manage as negotiations with the Zia regime moved forward. Outside of Pakistan and India, a nuclear arms race in South Asia was the last thing anyone wanted.

With Pakistani desires and Indian apprehensions in mind, U.S. intelligence services initiated an assessment of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development program and the impact of selling Islamabad F-16s. This was undertaken with the Reagan administration’s overall goal in mind of placating the Pakistanis while not giving them such a huge military advantage as to embolden them to either attack India, or worse yet, have New Delhi feel so threatened that India would attack Pakistan. Within eight months of Reagan’s inauguration, the CIA had produced, with the support of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the National Security Agency (NSA), and intelligence branches of the Departments of State (DOS) and the U.S. Department of the Treasury (USDT), a secret assessment of India’s understanding of, and potential responses to, Pakistan’s nuclear program and the ramifications of the Pakistan Air Force’s acquisition of Fighting Falcons.

The classified document, titled India’s Reaction to Nuclear Developments in Pakistan, concluded:

The US proposal to sell F-16’s to Pakistan is now being associated by New Delhi with the potential Pakistani nuclear threat. Reporting received since 7 June, when Israel used F-16’s to destroy a reactor in Iraq, indicates that high-level officials in the Indian Government are genuinely alarmed about F-16’s going to Pakistan.

India fears that, with the F-16, Pakistan has the capacity to counterattack effectively against some Indian nuclear facilities. Moreover, it fears that a rearmed Pakistan backed by a US commitment will become more adventurous and hostile towards India.

The Indian Government probably is concerned its options are narrowing, that its contingency plans for stopping the Pakistani nuclear program by force could not be implemented without inviting reciprocal attacks, which, if conducted with F-16’s, could not be adequately thwarted by existing Indian air defenses.”[25]

Armed with this assessment, the Reagan administration began to move forward with the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. Weighing their options, Reagan and his advisors coordinated with the U.S. military-industrial complex, e.g. the U.S. military assistance advisory group (MAAG) Pakistan and General Dynamics, and the State Department, and the Zia government, establishing an agreement to start selling F-16 aircraft to Pakistan with certain caveats. One of the biggest stipulations, intended to mollify Indian concerns, was that the aircraft be sold without the ability to carry and deliver nuclear weapons.[26] Indeed, so sensitive was this particular topic that almost a decade after the initial deliveries of F-16s to Pakistan, DOS was still placating the U.S. Congress, stating in 1989 that no F-16s purchased by Pakistan previously were configured for nuclear delivery, and furthermore, Pakistan was not allowed to modify any of the F-16s without express consent from the United States.[27] The Pakistanis were displeased with this arrangement, but their desire to acquire the aircraft prevailed. In December 1981, Zia’s military government signed an agreement for the purchase of 40 F-16s. The first group of six aircraft was delivered ten months later, in October 1982.[28]

As efforts to arm the mujahideen and provide aid to Pakistan progressed, Zia and Reagan planned to meet in December, 1982. This engagement was arranged to bring clarity to the goals and objectives of the ongoing effort, a meeting of the minds so to speak. Although this meeting is referred to in secondary sources, there is now declassified information about Washington’s posturing based on recently declassified documents prepared for the meeting.

President Zia Goes to Washington

President Zia headed to Washington D.C. knowing what he wanted to accomplish. A dictator, he was rightly accused of human rights violations by the Carter administration; however, this had problematized relations between the two presidents. Zia and Reagan though saw an opportunity to renew the mutual relationship between their countries based on the circumstances they found themselves in.

In preparation for this meeting, the State Department, in cooperation with several U.S. intelligence services, produced a secret document to inform Reagan on the status of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development efforts. A briefing by CIA analysts was scheduled in conjunction with the President’s review of the assessment. The secret document was titled “Conveying U.S. position on Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons program to President Zia during his December visit.” This briefing, now declassified, included a segment dealing with strategy, and how Reagan could approach Zia with respect to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program. The sticking point was that, in accordance with the numerous nuclear non-proliferation treaties now in existence, the United States would have to suspend aid to Pakistan if it could be proven that the Pakistanis were developing a nuclear weapon. The briefing document is sui generis in that it includes portions written in first person and incorporates the analyst’s logic and thought processes on how and why other analysts made their recommendations. (Italicized words are this author’s emphasis). The four options to be presented to Reagan were:

Option 1. Zia is told that if the program to procure components and to develop and manufacture a nuclear explosive device continues, or if international safeguards are violated, the U.S. will terminate economic and military assistance to Pakistan. . . . We should not . . . pursue this option unless, if necessary, we intend to follow through and terminate aid.

Option 2. Since Option 1 presents the President with a stark and difficult choice, we might consider a variation in which the President would tell Zia that the continuation of efforts would cause us to reassess our relationship with Pakistan. While reminding President Zia of the recent delivery of six F-16’s, the President would point out that during any reassessment, we would not be in a position to continue deliveries of any major military equipment.

Option 3. The President tells Zia that if the program to procure components and to develop and manufacture a nuclear explosive device continues, or if there is unsafeguarded reprocessing, it would seriously jeopardize our ability to provide military and economic assistance to Pakistan. This option would increase the pressure on Zia to restrict Pakistan’s nuclear weapons-related activities without binding the Administration to any particular course of future action.

Option 4. Zia is told by the President that the U.S. remains concerned about the direction of the Pakistani nuclear program, that it has carefully considered Pakistan’s assurances on its nuclear activities, and that violation of those assurances by a nuclear test … would force the U.S. to reconsider its assistance programs. This course . . . would permit the Pakistanis to carry out unsafeguarded reprocessing (which they are about to begin) and to procure components and machinery for fabrication of components of a nuclear device (which they are continuing to do). Proponents of this option believe there is a strong possibility that Pakistan would agree to this formulation and abide by it. Unlike the other Options, this course avoids . . . a continuation of present Pakistani activities . . . proponents believe this course alone can avoid a near-term confrontation between the U.S. and Pakistan.[29]

The analysis of the Options in this document is striking. It is readily apparent that the U.S. intelligence services were well aware of the status of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development program. In Options 3 and 4, the intelligence analysts identify alternatives for the president short of terminating aid to Islamabad, despite Pakistan violating International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) nuclear safeguards.

Reagan and Zia met at the White House on December 7, 1982. As Kux states, “Zia and Reagan met alone for 20 minutes in the Oval Office before joining their senior advisors in the cabinet room for another half hour of talks. In their private session, Reagan raised U.S. concerns about Pakistan’s nuclear program.[30] That same day, a White House spokesperson stated that President Zia assured President Reagan that Pakistan’s nuclear program was strictly for peaceful purposes only, and that the administration believes Zia is telling the truth.[31] However, Reagan kept to himself a statement Zia later passed to him in confidence–Muslims have the right to lie in a good cause.[32]

Zia also used his highly publicized visit to Washington D. C. to improve his image with the international news media. Kux mentions, “Skilled at public relations, an ever-smiling and amiable Zia handled himself adroitly on Capitol Hill and with the press during his stay.” Although Afghanistan was the main focus of questions, Pakistan’s president maintained his composure in the face of often hostile queries regarding Pakistan’s nuclear program and its human rights record. Meeting with members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he repeated ‘emphatically,’ according to Senator Charles Mathias (R-MD), that Pakistan was not seeking a nuclear weapon.”[33]

Credit: Dennis Kux. Disenchanted Allies: The United States and Pakistan, 1947-2000. (Baltimore: The Johns

Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Stalemate

With an agreement in hand, Washington and Islamabad moved forward in their support of the mujahideen. The United States also delivered economic and military aid to Pakistan, with the much-anticipated F-16s delivered on schedule, so that by 1987 the order of 40 Vipers were in the Pakistan Air Force inventory.[34] With military equipment consistently reaching the mujahideen, the war in Afghanistan stalemated. The Afghan Freedom Fighters started to utilize unconventional tactics similar to those used by the Viet Cong against the Americans during the Vietnam War. The Soviets occupied the cities of Afghanistan, while the insurgents controlled the countryside. When moving military units from city to city, the Soviets traveled in armed convoys, and this is when the mujahideen frequently attacked. When the Soviet soldiers did attempt armed incursions into the countryside, the Afghans would often refuse to confront them openly, disappearing into the hills and valleys that dominated the landscape.[35]

The U.S. government continued the battle on other fronts, leveraging international media outlets to put pressure on the Soviet government by highlighting examples of violence perpetrated by the Soviet Army on Afghan civilians. A flow of administration officials, cabinet members, and legislators with media in tow, paraded to Afghan refugee camps that had cropped up just across the border in Pakistan’s NWFP. Though the conditions of the camps were deplorable and their refugees rife with hunger and disease, they made for humanitarian stories and good press.[36]

Enter the Stinger

October 1986 brought about a game changer in the war: first operational use by the mujahideen of the American made, shoulder mounted, surface to air Stinger missile. The Stinger missile system was state of the art, highly technical, and successful in shooting down Soviet aircraft, especially the Mi-24 Hind ground attack helicopter. The Hind had become the cornerstone of Soviet military tactics in Afghanistan. With its weapon system of rockets and cannon, it would fly at low altitude destroying targets and terrorizing Afghan civilians and combatants alike.[37]

However, getting the Stinger missile into the hands of the mujahideen required overcoming obstacles, including the fact that the Stinger was an American produced weapon and its discovery on the battlefield by the Soviets would be problematic. Zia initially dragged his feet in allowing the Stinger missile system to be routed through Pakistan.[38] Up to this point all the CIA-supplied armaments were refurbished Soviet weapons, which gave Zia and Reagan plausible deniability with respect to involvement in supporting the mujahideen. Zia assumed he had enough problems of his own without provoking a Soviet blowback against his regime.

Zia was not the only source of resistance to the introduction of the Stinger. On the American side, opposition was at first stiff from Department of Defense (DoD) personnel, who worried that captured Stingers could be reversed engineered by the Russians. However, by this stage of the war U.S. aid to the Afghans was by and large an open secret. After considerable debate, the Reagan administration relented and overrode DoD and intelligence community concerns about releasing the Stinger to the Pakistan Army and Afghan rebels.[39] By late summer of 1986 Stingers were on the battlefield, and Soviet aircraft, particularly the Mi 24 Hind helicopters, started falling from the sky in alarming numbers. The Soviets were at a crossroads.

Credit: Image downloaded from https://www.google.com/search/Mujahideen/Stinger/Images

A change in attitude about the war’s status had started to build in 1985. Up to this point there was consensus among the American intelligence services that the best possible outcome in Afghanistan was deadlock. Afghans bleeding the Russians white without any American soldiers getting killed remained the goal. However, despite a significant buildup in Soviet troop presence, the Russians were not making appreciable gains in Afghanistan. A feeling emerged among the American advisors that the mujahideen could, if not flat-out win the conflict, force a Soviet withdrawal.[40]

Another factor materialized at this time. It was a change in leadership at the top of the Kremlin. Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the USSR in 1985. He was a different breed than the old Stalinist hardliners that preceded him, such as Leonid Brezhnev and Yuri Andropov. Gorbachev listened to the media outside of the Kremlin and wanted to bring the Soviet Union more into line with the rest of the world. He was about to get his chance.[41]

A Change in the Tide

As the war in Afghanistan tilted against the Soviet occupiers, Moscow began to look for options to extricate itself from its misadventure. A military solution seemed increasingly remote, as conventional tactics became less productive. Airstrikes against insurgent camps on the Afghan – Pakistan border had become costly due to Pakistan’s use of their FIM-92 Stingers and F-16s, which were capable of shooting down hostile aircraft straying into Pakistan’s airspace.

The Reagan administration realized that Soviets were back on their heels, and in response accelerated efforts to aid the mujahideen and to manipulate the international press. Deliberate attempts to expose Soviet Army atrocities continued, with images of slaughtered Afghan women and children reported by the media.

With pressure mounting on all sides, and seeing no end in sight, Gorbachev authorized negotiations for a withdrawal from Afghanistan. Meetings ensued in Geneva, Switzerland, on conditions for an end to the Soviet occupation. After much dialogue, the Soviets started a gradual withdrawal in April 1988, slowly transitioning security responsibilities to the communist proxy government in Kabul. In February1989, the last Soviet troops departed Afghanistan.[42]

Following the exit of the Soviets, Washington began the process of redefining the American role in South Asia. The Soviet Union collapsed shortly after exiting Afghanistan and with it went much of Pakistan’s geostrategic significance. Washington reduced aid to Islamabad and Pakistan had to look elsewhere for a strategic partnership, China for example. In 1990, during the George H. W. Bush administration, irrefutable evidence surfaced publicly that Pakistan was resolute in pursuing the development of a nuclear weapon, which further dampened relations with the United States. Worse yet, these revelations triggered sanctions of the Pressler Amendment. This legislation had been passed in the U.S. Congress requiring annual certification that Pakistan did not have, or did not make progress toward acquiring, a nuclear weapon.[43] Penalties of violating this amendment included a requirement that the United States freeze all military aid to Pakistan, and at the time that included an order of twenty-eight F-16 aircraft already on the books; aircraft the Zia military regime had contracted and paid for.

Conclusion

The relationship between the United States and Pakistan during the Soviet-Afghan war was essentially one of circumstance and convenience. To achieve geopolitical aims in Afghanistan, the Reagan administration essentially turned a blind eye to Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development program while supplying the Pakistan military with advanced conventional weaponry that suited it well in its dispute with India. This aid, however, was not given carte blanche. Declassified CIA and DOS documents reveal the Reagan administration was well briefed and versed in Pakistan’s desires, as well as Indian and Soviet concerns.

Taking these matters into consideration, the Reagan administration took a nuanced approach, in a sense playing both sides of the table, on several matters, including the decision to proceed with delivery of F-16s to the Pakistan Air Force, while not including the equipment necessary for these aircraft to deliver nuclear weapons. Reagan also invited Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to the White House for talks in 1982. In 1985, along with an Oval Office meeting he held a state dinner for her son Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Reagan had a good sense of Pakistan’s nuclear program prior to his meeting with Zia in December 1982. He was prepared and ready with several options when conducting one-on-one, behind closed door diplomacy and attendant diplomatic discussions with Zia. As the Soviet–Afghan war ground to a stalemate, CIA assessments revealed the Russians were floundering as they tried to disrupt U.S.-Pakistan cooperation. This information emboldened the allies to increase support for the mujahideen and hastened the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan.

At a strategic level, Islamabad indirectly used American assistance during the Soviet-Afghan conflict to continue development of a nuclear weapon. With large amounts of American economic aid pouring into the country during the 1980s, the Zia regime discreetly funneled resources to initiatives as development of a nuclear triggering device and machining nuclear bomb cores.[44] While consistently claiming to the international press that no such effort was in progress, Islamabad deliberately and methodically took the steps necessary to further the goal of nuclear weapons development. The activation of the Pressler Amendment and subsequent cessation of aid from the United States in 1990 did slow Pakistan’s nuclear weapons development, but it did not stop it. On May 28, 1998, Pakistan joined the nuclear club by detonating an atomic device at the Ras Koh testing facility in Baluchistan province.[45]

And what of those 28 F-16s sent into limbo at Davis-Monthan AFB as a result of the Pressler Amendment sanctions taking effect in 1990? After unsuccessful attempts to either sell or lease the aircraft to other international customers, it was decided to give the F-16s to the USN. The seafaring branch of the U.S. military would use the F-16s as aggressor aircraft at their Fighter Weapons School (FWS), more commonly known as Top Gun. Here the Vipers would play the role of enemy aircraft in the training of Navy fighter pilots.[46]

After the F-16s had been delivered to the Navy’s FWS, the Clinton administration had to decide what to do about paying back Pakistan for aircraft that Islamabad was not going to receive. In 1999, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif met with President Bill Clinton for diplomatic talks. Clinton decided to refund the Pakistan government the $470 million in cash of the total $610 million Islamabad had laid out. The balance of the refund was partially in the form of agriculture products to be shipped to Pakistan. Eight years after the Pressler Amendment went into effect and military credits were suspended to Pakistan, the issue was resolved amicably.[47] Though there were some armament and military equipment deliveries, they were not the remaining F-16s.

On September 11, 2001, Muslim extremists hijacked four commercial passenger airliners and used them to attack iconic American landmarks and targets, including the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington D.C.-Arlington, Virginia. In the aftermath of these terrorist attacks, U.S. intelligence agencies determined they were the brainchild of a Muslim extremist named Osama Bin Laden and the Al Qaeda terrorist organization. Al Qaeda had numerous training camps in Afghanistan.

The George W. Bush administration launched negotiations with the Government of Pakistan headed by President Pervez Musharraf. Foremost was a call for permission to allow American troops and associated military equipment to transit through Pakistan in order to conduct combat operations against Al Qaeda strongholds in Afghanistan’s Kandahar province.[48] Similar to the situation in 1980, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, Musharraf negotiated with the Bush administration. The Pakistan Armed Forces assembled a list of military aid and arms transfer requests in exchange for granting American wishes. Political and diplomatic names had changed, but the game was the same. At the top of Pakistan’s military hardware requirements list was a call to purchase 40 new F-16 fighter aircraft.[49]

After much deliberation, hand wringing, and gnashing of teeth amongst the power brokers in Washington D.C., the request was approved.[50]

Credit: Image downloaded from https://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html

Notes

[1] Personal recollections of author.

[2] Daniel S. Markey, No Exit from Pakistan: America’s Tortured Relationship with Islamabad (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 95.

[3] Dennis Kux, The United States and Pakistan 1947-2000: Disenchanted Allies, (Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Press, 2001), 267.

[4] A.Z. Hilali, US-Pakistan Relationship: Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, 2005), 194.

[5] Hilali, 145.

[6] Markey, No Exit, 94.

[7] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 194.

[8] Hilali, 118.

[9] Hilali.

[10] Markey, No Exit, 96.

[11] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 396.

[12] Kux, 242.

[13] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 118.

[14] Markey, No Exit, 94.

[15] Markey, 95.

[16] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 252.

[17] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 83.

[18] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 245.

[19] Rathnam Indurthy, India-Pakistan Wars and the Kashmir Crisis, (New York: Routledge Focus Press, 2019), 1.

[20] Indurthy, India-Pakistan, 6.

[21] United Nations, Office for Disarmament Affairs, Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT),https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text (accessed November 3, 2020).

[22] “Timeline of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Fact Sheet,” Arms Control Association, https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-the-Treaty-on-the-Non-Proliferation-of-Nuclear-Weapons-NPT (accessed November 3, 2020).

[23] Markey, No Exit, 95.

[24] R.M.S. Azam, F-16.net, http://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html (accessed November 3, 2020).

[25] Central Intelligence Agency, India’s Reaction to Nuclear Developments in Pakistan, 8 September, 1981, Special National Intelligence Estimate 31/32-81.

[26] F-16 Fighting Falcon (General Dynamics), https://fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/aircraft/f-16.htm#:~:text=Of%20the%2040%20F%2D16,1990%20by%20the%20United%20States (accessed November 3,

[27] “Pakistan has 130-140 nuclear weapons, converts F-16 to carry nukes,” The Economic Times. November 19, 2016, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/pakistan-has-130-140-nuclear-weapons-converts-f16-to-deliver-nukes/articleshow/55508071.cms (accessed 18 April, 2021).

[28] R.M.S. Azam, F-16.net, http://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html (accessed November 3, 2020).

[29] United States Department of State, Restricted Interagency Meeting on Pakistan’s Nuclear Program, 16 November, 1982, CIA-RDP84B00049R000501260015-7.

[30] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 268.

[31] Kux, 268.

[32] Kux, 289.

[33] Kux., 268.

[34] R.M.S. Azam, F-16.net, http://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html (accessed November 3, 2020).

[35] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 273.

[36] Kux, 271.

[37] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 170.

[38] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 281.

[39] Kux.

[40] Kux.

[41] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 170.

[42] Hilali.

[43] Robert M. Hathaway, “Confrontation and Retreat: The U.S. Congress and the South Asian Nuclear Tests,” Arms Control Association, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2000-01/confrontation-retreat-us-congress-south-asian-nuclear-tests-key-legislation (accessed November 3, 2020).

[44] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 310.

[45] “Ras Koh Test Site,” NTI. March 1, 2011. https://www.nti.org/learn/facilities/122/ (accessed November20, 2020).

[46] R.M.S. Azam, F-16.net, http://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html (accessed November 3, 2020).

[47] Kux, Disenchanted Allies, 351.

[48] Hilali, US-Pakistan, 254.

[49] Markey, No Exit, 123.

[50] Markey.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Central Intelligence Agency, Pakistan/USSR: The Soviet Campaign Against Pakistan’s Nuclear Program 7 August, 1987, CIA-RDP90T00114R000700470001-0, Washington, D.C. (Declassified 7 May, 2012).

Central Intelligence Agency, India’s Reaction to Nuclear Developments in Pakistan, 8 September, 1981, Special National Intelligence Estimate 31/32-81, Washington, D.C. (Declassified 30 November, 2009).

United States Department of State, Restricted Interagency Meeting on Pakistan’s Nuclear Program, 16 November, 1982, CIA-RDP84B00049R000501260015-7, Washington, D.C. (Declassified 30 July, 2009).

Secondary Sources

Azam, R.M.S. “Pakistan.”F-16.net. http://www.f-16.net/f-16_users_article14.html (accessed November 3, 2020).

Chaudhuri, Rudra. Forged In Crisis. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

“F-16 Fighting Falcon (General Dynamics).” Federation of American Scientists. https://fas.org/nuke/guide/pakistan/aircraft/16.htm#:~:text=Of%20the%2040%20F%2D16,1990%20by%20the%20United%20States (accessed November 3, 2020).

Hathaway, Robert M. “Confrontation and Retreat: The U.S. Congress and the South Nuclear Tests.” Arms Control Association, https://www.armscontrol.org/act/2000-01/confrontation-retreat-us-congress-south-asian-nuclear-tests-key-legislation (accessed November 3, 2020).

Hilali, A.Z. US-Pakistan Relationship: Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005.

Indurthy, Rathnam. India-Pakistan Wars and the Kashmir Crisis. New York: Routledge Focus Press, 2019.

Kux, Dennis. Disenchanted Allies: The United States and Pakistan, 1947-2000.Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

Levy, Adrian and Catherine Scott Clark. Deception. Prince Frederick: Recorded Books, LLC, 2007.

Maley, William. The Afghanistan Wars. New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009.

Markey, Daniel S. No Exit From Pakistan: America’s Tortured Relationship with Islamabad. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

“Ras Koh Test Site.” NTI. March 1, 2011.https://www.nti.org/learn/facilities/122/. (accessed November 20, 2020).

“Timeline of the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Fact Sheet.” Arms Control Association. https://www.armscontrol.org/factsheets/Timeline-of-the-Treaty-on-the-Non-Proliferation-of-Nuclear-Weapons-NPT (accessed 3 November 2020).

“Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).”United Nations, Office for Disarmament Affairs. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wmd/nuclear/npt/text (accessed November 3, 2020).

United States Department of State. “Reagan Doctrine.” U.S. Department of State, 1985. https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/rd/17741.htm (accessed November 3, 2020).