“We Shall Not Be Moved”: The National Discourse of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, 1934-1936

By: Kathryn Leonard

“When thinking of how horrid the past has been,

And know the labor road hasn’t been smooth.

Deep down in your heart you keep singing:

‘We shall not, we shall not be moved!”

– John Handcox, Be Consolated[1]

In July of 1934, a group of eleven white and seven black sharecroppers and tenant farmers met at the Sunnyside Schoolhouse on the outskirts of Hiram Norcross’s Fairview Plantation just outside of Tyronza, Arkansas to discuss their situation. The lives of tenant farmers and sharecroppers had long been defined by privation, racial division, and bare subsistence, but the New Deal’s Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933 made matters worse. The landlords who kept these croppers and tenants in a state of near-slavery and debt peonage agreed to plow up one-third of their cotton crop in exchange for government subsidies (called “parity payments”) and, hopefully, higher market prices in coming years. Although the AAA’s Cotton Contract obligated landlords to share these payments with their tenants and allow them to live on their current plantations rent-free in 1933 and 1934, this part of the contract was rarely enforced.[2] Landlords like Norcross evicted many tenant families as superfluous. Homeless and penniless, these families cried out for assistance. An interracial group of dejected and angry sharecroppers and tenant farmers decided that collective action was the only way forward. They called their new organization the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union (STFU). [3]

The story of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union has been told several times over, with historians debating its successes (some) and failures (many), as well as its unique history as an interracial grassroots union in the segregated 1930s South. While many historians get bogged down in the scorekeeping paradigm of successes and failures, they only casually mention the primary skill of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union: creating publicity for the plight of tenant farmers and sharecroppers throughout the South. In both publishing and inspiring accounts in national newspapers, journals, and books, STFU leaders and supporters, including perennial Socialist Party presidential nominee Norman Thomas, created a national discourse of the evils of the sharecropping system in the cotton South. By examining the nationally published contemporary discourse surrounding the STFU and the plight of tenants in the American agricultural South, I argue that the STFU used the power of the press to bring awareness, incite outrage, and eventually inspire government action to alleviate the injustices suffered by Black and white sharecroppers and tenant farmers in Arkansas and beyond.

The historiography of the STFU has gone through many shifts since David Conrad published the first book-length study of the AAA and the union in 1965.[4] Early sources tell a heroic story of the STFU desperately fighting for the rights of oppressed Black and white sharecroppers and tenant farmers in the Arkansas Delta.[5] Others tell a more measured tale of an imperfect union that had many shortcomings, but at least tried to help people.[6] Some historians are blatantly cynical, portraying the STFU as an ineffective union committed to racial and class unity in theory but disconnected from its membership in practice.[7]

While most of these historians mention the STFU’s use of the press, they only tangentially address the true sources of power and success in the STFU: publicity, sympathy, and outrage. By calling attention to the plight of the sharecroppers and tenant farmers in the Delta, the STFU provoked action. Nan Woodruff comes the closest to recognizing the power of publicity for the STFU, noting how “outside supporters, writers, and journalists publicized life in the American Congo for all to see.”[8] Although many historians admired the STFU’s ability to create and utilize publicity to raise national awareness of the sharecropper situation in Arkansas, few have fully examined the impact of this discourse.

To show how the STFU used publicity to confront systemic inequalities in the sharecropping system in the agricultural South, I will examine the union discourse in national publications such as the New York Times, Time Magazine, The Nation, and the NAACP publication The Crisis. I will also examine contemporary pamphlets and books written by STFU ally Norman Thomas and union scribe Howard Kester to show how insiders portrayed the STFU to a national audience. Finally, I will examine the medium that reached the most people in 1936: the cinema. Through these sources, I hope to illustrate that while the STFU was far from perfect as a labor union dedicated to improving the lives of sharecroppers and tenants, it was an excellent source of publicity for their plight and eventually inspired government action on their behalf.

“Raggedy, raggedy are we”[9]

The story of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union begins with the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) of 1933. Part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to alleviate the effects of the Great Depression, the AAA attempted to raise the international price of commodities like cotton by reducing the supply. The AAA was a tremendous boon for planters, especially in the cotton industry, where the price had fallen to 4 cents per hundred pounds during the Great Depression.[10] But its many loopholes enabled planters to cheat sharecroppers and tenant farmers out of their fair share of agricultural profits by reducing the amount of cotton grown and sold.

This 1937 photograph shows a run-down tenant shack with cotton planted up to the doorstep. Tenants were not allowed space for vegetable gardens, and many suffered from malnutrition.[11]

Matters in the Arkansas Delta came to a head in January of 1934 when Hiram Norcross, a St. Louis lawyer and absentee landlord who owned the Fairview Plantation outside of Tyronza evicted a number of tenants, in violation of the AAA Cotton Contract.[12] Other planters followed suit. Dejected and desperate, sharecroppers and tenant farmers near Tyronza turned to two local businessmen with reputations for fairness to all races: Clay East, who owned a local gas station, and H.L. Mitchell, who owned a dry-cleaning business. East and Mitchell were both members of the local Socialist Party and were heavily influenced by socialist politician Norman Thomas.[13]

At their first meeting at the Sunnyside Schoolhouse, the interracial gathering of sharecroppers and sympathizers that formed the STFU decided to unite to protect themselves from the power of the landlords, fight evictions, and advocate for their fair share of the AAA parity payments and cotton profits. The gathering eschewed KKK-style night riding and violence in favor of creating a legally-recognized organization.[14] They also discussed the delicate issue of race. According to historian Jeannie Whayne, data from the 1920 census indicated that 54.3% of all farmers in the Arkansas Delta were Black. Of those Black farmers, only 3.8% owned their own land, compared to 11% of white farmers in the region. Thus, approximately 96% of Black farmers in the Delta were either tenant farmers or sharecroppers, while 89% of white farmers fell into those same categories.[15] In the Delta, both races faced the iniquities of the sharecropping system, especially when it came to evictions. In Tyronza, Hiram Norcross was an equal-opportunity villain and evicted tenants regardless of their skin color, uniting the local tenants in their opposition.

The gathering debated the merits of two segregated unions versus a single interracial one. In his 1936 account of the STFU, Revolt Among the Sharecroppers, union scribe Howard Kester recounted the discussions on that July day. He quoted “an old man with cotton-white hair overhanging his ebony face,” who H.L. Mitchell later identified as Isaac Shaw. Shaw “had been a member of a black man’s union at Elaine, Arkansas. He had seen the union with its membership wiped out in the bloody Elaine Massacre of 1919.”[16] Shaw realized that, without white participation, the landlords could divide the sharecroppers and annihilate the Black activists, as they had in Elaine, and negate the white ones due to their smaller numbers. Kester quoted Shaw: “For a long time now the white folks and the colored folks have been fighting each other and both of us has been getting whipped all the time. We don’t have nothing against one another but we got plenty against the landlord.”[17] According to Kester’s account, Shaw reminded the gathering, “The landlord is always betwixt us, beatin’ us and starvin’ us and makin’ us fight each other. There ain’t but one way for us to get him where he can’t help himself and that’s for us to get together and stay together.”[18] With a biracial union, the planters could no longer play white tenants against Black. On that day in Tyronza, Arkansas sharecroppers tentatively put aside racial divisions in the interest of working together against their common enemy: the landowners.

While Arkansas landlords and their agents worked to thwart the union using violence and intimidation, union sympathizers immediately got to work bringing national awareness to the struggle of southern sharecroppers. In 1934, STFU ally Norman Thomas wrote a pamphlet entitled The Plight of the Share-Cropper, published by the Socialist League for Industrial Democracy in New York. Thomas described the Arkansas Delta as “a country where cotton is still king, a king who rewards his humblest subjects and his most loyal workers with poverty, pellagra, and illiteracy.”[19] The Arkansas plantation landlord “does the figuring” to determine debts and payments, often “with a ‘crooked pencil,’” and “If the tenant is illiterate it is hard for him to check up on this reckoning and often, especially is he is a Negro, he dare not protest.”[20] Thomas argued that this system of dubious debt “means peonage, even for the white tenant, a peonage made deeper and more inescapable if the tenant is further disadvantaged by being a Negro.”[21] Thomas alerted northern workers to the struggle of their southern brethren against an abusive system of poverty, starvation, and exploitation that dominated the cotton South, and judging by the number of printings, he succeeded in reaching a large liberal and Socialist audience with his pamphlet. As the STFU’s unofficial national spokesperson and political cheerleader, Norman Thomas brought the STFU cause to a national audience. The Plight of the Share-Cropper was the first volley in the STFU publicity war against the planters.

“There is mean things happening in this land”[22]

In January of 1935, the union received its first significant national media exposure due to the words and actions of STFU organizer Ward Rodgers, a Methodist minister and adult education teacher for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). On January 15th, Rodgers, H.L. Mitchell, and Black union Vice President E.B. McKinney spoke to an estimated crowd of 1,500 at a mass meeting in Marked Tree, Arkansas. According to an account in Time magazine entitled “Bootleg Slavery,” Rodgers, who was overcome by the emotion of five months of anti-union violence and evictions by local planters, told the crowd, that “he was willing, if share croppers were not fed, to ‘lynch every plantation owner in Poinsett County.’”[23] The crowd cheered wildly. Rodgers then introduced the next speaker, “Mister” E.B. McKinney. Local authorities immediately reacted to Rodgers’s word choice: it was scandalous for a white man to call a Black man “Mister” in Arkansas in 1935. Poinsett County attorney Fred Stafford arrested Rodgers on the spot, charging him with “anarchy” and “blasphemy.”[24] The national press, there to cover the event at the urging of Norman Thomas, reported every detail of the meeting, the Rodgers trial, and the STFU’s struggle in Arkansas.

Black and white men, women, and children at a STFU meeting, 1937. The woman in the kerchief is Myrtle Lawrence, a powerful union organizer.[25]

E.B. McKinney, STFU Vice President (left), standing with two unidentified men, one of whom holds a gun, 1937.[26]

The media coverage of the Ward Rodgers affair lasted well into the spring of 1935 and brought the tense situation in Arkansas to a national audience. On January 22, the New York Times reported on Rodgers’s arrest and trial with the headline “FERA Teacher Convicted Of Anarchy in Arkansas.”[27] The Nation, a liberal weekly magazine, addressed the Rodgers incident in its February 6th issue, arguing that the “central issue in Mr. Rodger’s case is not anarchy but his activity in organizing the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, which admits both blacks and whites and which is attempting, among other things to prevent the eviction of share-croppers.” The editorial recommended “that newspapers in search of good dramatic American copy might well transfer a few reporters… to Marked Tree, Arkansas.”[28] Rodgers’s conviction for anarchy and blasphemy focused the media’s attention on Arkansas, and created a discourse about the revolutionary interracial composition of the STFU.[29] The struggle between the STFU and Arkansas planters certainly made for dramatic reading.

In April, journalist F. Raymond Daniell published a series of articles about the STFU in the New York Times that exposed the tense situation between the STFU and the cotton planters in Arkansas. The first, which appeared on April 15th, discussed the tenant situation in the Arkansas Delta since the passage of the AAA: “For many of them, the “Three A’s” have spelled unemployment, shrunken incomes and a lowered standard of living, if the hand-to-mouth existence they have led since the war between the States may be called living at all.” Daniell continued, “Scores have been evicted or ‘run off the place’ for union activity, and masked night riders have spread fear among union members, both white and Negro.”[30] With his first article, Daniell raised awareness of both the plight of sharecroppers and the planters’ violent reactions to the STFU in Arkansas. Future articles elaborated on this situation.

On April 16th, Daniell addressed the reign of terror in Marked Tree that followed Rodger’s arrest in January. Marked Tree became “the scene of the mob violence to which, workers say, the landlords and riding bosses of the big plantations have resorted in their effort to stamp out the seeds of unionism,” as the landlords and their agents violently attacked STFU members and leaders and denounced the biracial union in the press. Daniell interviewed landlord spokesman Reverend J. Abner Sage of the First Methodist Church in Marked Tree, who accused sharecroppers of being “a shiftless lot with only themselves to blame if they are not as well blessed with this world’s goods as they would like to be.” Sage also took issue with Rodgers referring to McKinney as “Mister,” quoting, “‘We’ve had a pretty serious situation here, what with the mistering of those n—–s and stirring them up to think the government was agoin’[sic] to give them each forty acres.’” Sage contemplated, “‘I don’t know, though, but that it would have been better to have a few no-account shiftless people like that killed at the start than to have had all this fuss raised up.’”[31] Sage’s words revealed the classist and racist attitudes of Arkansas planters to a national audience. Although Daniell maintained journalistic neutrality throughout the series, his account of anti-union violence and his interview with Sage turned northern sympathies in favor of the STFU.

On April 19th, Daniell addressed the interracial nature of the STFU. He described that “Mixed meetings of white and Negro men were held on the main streets of the towns. Economic and social equality of black and white was preached at these meetings, and Negroes were introduced as ‘Mister.’” Daniell continued, “white members shook hands with Negro members when they met on the street, and they began calling each other ‘comrade’ to the amazement and disgust of the planters, who seized upon the race issue as an excuse for the reign of terror which has followed in the wake of efforts to unionize the share-croppers.” [32] The integrated nature of the STFU infuriated planters, who used race to divide and conquer sharecroppers for decades. Daniell’s discussion of the STFU’s policy of interracial cooperation, planter violence, and racial and class prejudice in Marked Tree increased the national discourse surrounding race, the violent injustices of the agricultural South, and the STFU’s efforts on behalf of sharecroppers regardless of color.

In June of 1935, Ward Rodgers wrote an article for the NAACP newspaper The Crisis arguing for interracial cooperation to confront systemic inequalities in the South. In “Sharecroppers Drop Color Line,” Rodgers argued that the interracial STFU existed because of mutual suffering: “The sharecroppers, regardless of color, have been deprived of a living which certainly they work hard enough to earn. Both races have been driven down to a low economic level of bare existence.”[33] He then detailed the economic inequalities of the sharecropping system, the reign of terror that the planters unleashed upon the STFU, and the failure of the state or federal government to help. He concluded with a plea to help the STFU “build a new South.”[34] By arguing for a unified racial front against planter oppression in the South, Rodgers hoped to paint the STFU and other interracial organizations as the antidote to southern inequality. This article appeared in the nation’s top Black newspaper, and is significant as a moment of racial outreach from an interracial organization that confronted systemic injustice in the South.

As Rodgers attempted to rouse national African American sympathy for the STFU, Norman Thomas addressed the planter reign of terror to a wider national audience. In the spring of 1935, Thomas spoke on NBC radio to broadcast his concerns to the nation after riding bosses violently forced him to flee Birdsong, Arkansas. Thomas warned, “‘There is a reign of terror in the cotton country of eastern Arkansas. It will end either in the establishment of complete and slavish submission to the vilest exploitation in America or in bloodshed, or in both. For the sake of peace, liberty and common human decency I appeal to you who listen to my voice to bring immediate pressure upon the Federal Government to act.’” Thomas called on the nation to reject the violent repression of free speech and to hold the Arkansas planters to account for their campaign of violence and intimidation that had driven him from Birdsong. Thomas continued, praising the resilient STFU: “‘The union fought for its life as few dreamed that it could. At the end it counted its dead, its injured, its wrecked and blighted lives by the scores but it emerged from the struggle a powerful, well-organized and fighting union which, if it continues along the road it has thus far traversed, may have a significant influence upon the future of American history.’” [35] By using his platform as a nationally-recognized politician, Norman Thomas called attention to the sharecroppers, the STFU, and the planters engaged in repressive terror in Arkansas. Thousands of listeners heard Thomas’s pleas for awareness, outrage, and action.

“We’re gonna roll the Union on”[36]

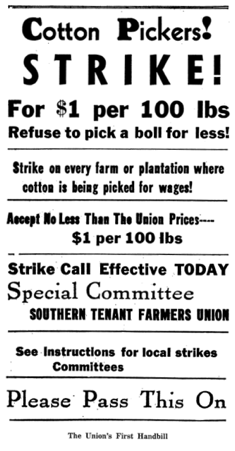

As cotton hoeing season arrived in May of 1935, the first reign of terror dwindled into a tense truce between the plantations and their laborers. In Revolt Among the Sharecroppers, published in early 1936, STFU activist Howard Kester victoriously remembered that “The back of the terror was broken not by resorting to the violent tactics of the defenders of the system but by the written word and the ceaseless activity of the thousands of disinherited men, women and children who lived for the union, but were ready to die that the union might live and bring some measure of peace, freedom and security to their children.”[37] Despite the animosity of the winter of 1935, both groups relied on cotton as a means of survival, and activism took a back seat to necessity for a few months, although the STFU continued to plot against the landlords. In September of 1935, the union organized their first successful labor stoppage, an Arkansas cotton-pickers’ strike that lasted for ten days and raised the rate for cotton picking from 40 cents to 75 cents per hundred pounds.[38] Hundreds of tenant farmers participated in the September 1935 strike, regardless of union membership, and it was one of the few tangible successful operations that the STFU organized against the landlords.[39]

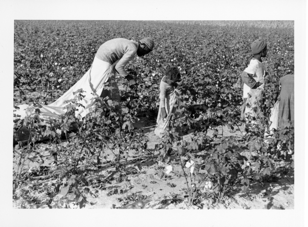

Black women and children picking cotton, 1937[41]

In late 1935, the leadership of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union was hopeful about the coming new year. They had just orchestrated their first successful collective action, where Black and white sharecroppers forced desperate landlords to raise their daily wages. But the landlords struck back. In January 1936, C.H. Dibble evicted one hundred tenants for being members of the STFU. The evicted tenants and their families set up a tent colony along the roadside in Parkin, Arkansas. While the union did what they could for these newly-homeless tenants, the landowners continued to terrorize union members and even threw a stick of dynamite into the tent colony. [42] A new “reign of terror” against the STFU had begun.

While the violence of 1935 brought national attention to the tiny town of Marked Tree, 1936 brought Earle, Arkansas into the spotlight. On January 16th and 17th, Earle deputies Everett Hood and Paul D. Peacher used violence to disrupt union meetings. The deputies and riding bosses beat men, women, and children, including Howard Kester, who presided over the January 17th meeting. Meanwhile, as Kester recovered from the violence in Earle, his words brought the plight of the STFU to a national audience. That same month, his brief history and philosophy of the STFU, Revolt Among the Sharecroppers, appeared in bookshops nationwide. Kester described the plight of evicted sharecroppers, “without homes, food, or work, half-clothed, sick of body and soul, unwanted and unloved in the Kingdom of Cotton which they have faithfully served but which no longer needs them.”[43] Kester blamed the evictions on the AAA, calling it “the greatest iniquity since the ‘bo’ evil’ [boll weevil], that economic monstrosity and bastard child of a decadent capitalism and a youthful Fascism, the AAA.”[44] Kester argued that the AAA “‘plowed under’ hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers in the South and reduced them to an all-time record of poverty, misery and hopelessness.”[45] Kester set the stage for a national audience to appreciate the hopeless situation of southern tenant farmers, made worse by the AAA.

Kester then celebrated the heroic STFU. “There is only one hopeful thing about the situation and that is the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” He continued, “For the first time in the history of the United States, perhaps in the history of the world, white and colored people are working together in a common cause with complete trust and friendship… for what is supposed to be everyone’s birthright – a decent standard of living, education, security, hope for the future.”[46] Despite its many shortcomings regarding race and labor organization, the STFU was truly revolutionary as a union committed to interracial cooperation. It is no wonder that some historians cite the STFU, no matter how imperfect, as one of the founding factors of the Civil Rights movement.[47]

“If you go through Arkansas, you better drive fast”[48]

In May of 1936, the STFU organized another cotton strike, seeking a wage increase to $1.25 per day. While the September 1935 strike had been a success, this one was a failure. The planters were prepared and used intimidation and payments to keep the workers in the field.[49] On June 8th, planters and riding bosses in Earle broke up a union meeting and severely beat white sharecropper Jim Reese, Black sharecropper Frank Weems, and several others with baseball bats, pistol butts, and axe handles. The riding bosses beat Reese so badly that he was permanently disabled, and Black sharecropper Eliza Nolden later died from her injuries. Frank Weems disappeared, and the union thought he was dead.[50] H.L. Mitchell organized a funeral for Weems, although no one had found his body, and asked Rev. Claude Williams to preside over the services. STFU activist Willie Sue Blagden, a white woman from a prominent Memphis family, joined Williams for the services.

On June 16th, in Earle, “six well-dressed white men” confronted and attacked Williams and Blagden. Blagden told her story on the pages of The New Republic: “Five men took Mr. Williams down the river, one remained with me. I counted fourteen cracks of the mule’s harness.” When they returned, “Mr. Williams was pale and shaken.” They then approached Ms. Blagden: “‘Now it’s your turn,’ one of them said to me I could hardly believe what I had seen and heard, and I did not believe they would beat me.” The men ordered her onto the ground. Blagden responded, “‘I will not.’ Then came the first crack. I think I laughed. Even then I could not believe it. What crimes have been committed for the ‘Honor of Southern White Womanhood’! A Negro is lynched if any white woman can be found who will say ‘He attacked me.’ Is it womanhood they are protecting when they flogged me?” Ms. Blagden recounted the beating: “Whizz! Through the air came the harness and I felt it blaze upon my thigh. Then again.” The men transported Blagden to the train station and sent her back to Memphis.[51] The planters continued to beat Claude Williams, then released him. America was outraged. Apparently, the beatings and deaths of Black sharecroppers and white tenant farmers were old news, to be expected. But to a shocked national audience, the beating of a white woman was unforgivable.

When Blagden returned to Memphis, she immediately contacted H.L. Mitchell who, true to form, immediately contacted the newspapers.[52] On June 17th, the New York Times broke the story to a scandalized nation. Norman Thomas was outraged. He sent an angry telegram to Roosevelt, which he provided for the New York Times: “‘Latest developments in Arkansas reign of terror includes the beating of a young woman, Miss Blagden, and the worse beating and kidnapping of the Rev. Claude Williams…. I appeal to you not only as President of the United States but as the leader of a great political party to act in this monstrous perversion of everything decent in the American tradition.’” By publishing this telegram in the Times, Thomas hoped to shame the president into action on behalf of the STFU and struggling tenant farmers in the South. It seemed, however, that FDR did not need any further prodding for action. According to the article, President Roosevelt pledged a full investigation by US Attorney General Homer Cummings.[53]

Time magazine also took notice of the violence in Arkansas. On June 29th, Time published an article entitled “True Arkansas Hospitality” that included a picture of Blagden’s injuries. The article reported: “Preacher Williams was lashed 14 times with a mule’s belly-strap. Miss Blagden’s turn came next. The huskiest of the six swung the belly strap, laid four solid clouts on her back & thighs.” Like Thomas, Time also had further commentary for President Roosevelt, who had just enjoyed a campaign stop in Arkansas: “Week prior, to 50,000 enthusiastic Democrats in Little Rock, Ark., Preacher Williams’ home, Franklin D. Roosevelt had felicitated himself on the opportunity ‘to enjoy the kindness and the courtesy of true Arkansas hospitality.’” The article continued, “The brand of Arkansas hospitality accorded Preacher Williams and Miss Blagden last week swung the spotlight of national attention on the 1936 Arkansas sharecroppers’ strike which had been fumbling along unnoticed for four weeks.”[54] By calling attention to ongoing violence between planters and the STFU, FDR’s inaction to stop it, the unsuccessful strike of May 1936, and the beating of a white woman and a preacher in Earle, these articles in the New York Times and Time signified an increasing sense of outrage in the national political discourse about planter violence in Arkansas.

Miss Blagden shows her bruises, Time Magazine, June 29, 1936[55]

In August, Hollywood contributed to this discourse with a poignant newsreel about the sharecroppers in Arkansas, the STFU, and the violence against Williams and Blagden. On August 7th, the RKO newsreel The March of Time: “King Cotton’s Slaves,” opened in an estimated 6,000 theaters nationwide. Thousands of moviegoers witnessed the horrors of southern sharecropping, the heroic efforts of the STFU, and a dramatization of the violence against Williams and Blagden. Thematically, the newsreel primarily celebrated the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union as the savior of the sharecroppers. With the Blagden assault and the heart-wrenching images presented to the movie-going public, the nation’s sympathies were firmly on the side of the brave STFU, fighting for the underdog and all that was good in the South.

“King Cotton’s Slaves” presented viewers with a vision of poverty and injustice in Arkansas. The newsreel began with the familiar voice of Westbrook Van Voorhis, who described the cotton South: “In all the United States, there is no parallel to the economic bondage in which cotton holds the South,” and showed images of both the white and Black victims of King Cotton. The film then switched to a young man urging tenants to fight for their rights, and a union meeting where STFU members sang “We Shall Not be Moved,” a popular union protest song. Climactically, the next scene depicted several men confronting Claude Williams and Willie Sue Blagden (portrayed by actors), based on Blagden’s account from The New Republic. Voorhis narrated: “The next day the violence in the Blagden-Williams investigation came into sharp focus for the entire nation.” It showed the newspaper headlines: “Eastern Arkansas Planters Flog Woman and Man.” The scene then shifted to Arkansas Governor J.M. Futrell, who blamed the cotton system and defended the planters. The film concluded, “It is plain today that planter and sharecropper alike are the economic slaves of the South’s one-crop system and that only basic change can restore the one time peace and prosperity of the Kingdom of Cotton. Time Marches On.”[56] The film’s juxtaposition of downtrodden sharecroppers, falsely sympathetic planters, union protagonists, a terrorized white woman, and an unsympathetic politician offered a blatant indictment of the situation in Arkansas.

In just eight minutes, The March of Time brought awareness, outrage, and sympathy to the sharecroppers in Arkansas and immortalized the STFU as the hero of a downtrodden people. The attack on Willie Sue Blagden and Claude Williams, replayed hundreds of times for thousands of Americans, brought the reign of terror to an end. As Attorney General Cummings investigated the Blagden-Williams assault, he uncovered cases of peonage and violence committed by Earle deputy Paul Peacher, who was convicted of peonage in November of 1936.[57]

It is difficult to overstate the impact of the Blagden-Williams beatings on the situation in Arkansas. The planter reign of terror against the union that started in July of 1934 suddenly and abruptly ended in 1936 with the reports of Ms. Blagden’s beating. After dozens of sharecroppers, Black and white, men and women, had been shot at, beaten, and terrorized for two years, the flogging of a white woman was the final straw. H.L. Mitchell later wrote, “The beating of a white woman and a white minister became a nationwide human interest story. No attention was paid to Eliza Nolden, a black woman soon to die from the effects of a severe beating,” nor to Jim Reese, injured for life, or Frank Weems, presumed dead until he surfaced in Illinois months later.[58] In the national psyche, by abusing a wealthy white woman, the planters in Arkansas had taken terror one step too far. Groomed by two years of press from Norman Thomas and the reporting of the New York Times, The Nation, and other publications, the American people demanded justice. The federal government could no longer ignore planter abuse in the South. As historian Jerold Auerbach wrote, “New crises awaited the union, but its right to exist and its ability to be heard were no longer in doubt.”[59] President Roosevelt, seeking re-election, responded by announcing a special commission on farm tenancy in August of 1936, which included the Reverend William Blackstone of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.

“No more mourning after a while”[60]

Following two years of agitation, strikes, pleas from powerful allies, and national publicity, the tenant farmers of the South had been heard. In January of 1936, the US Supreme Court overturned the AAA of 1933 on a technicality involving processing taxes.[61] In November of 1936, Roosevelt and Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace “acknowledged the upheaval in the rural South” when they established the President’s Committee on Farm Tenancy, which historian Pete Daniel credits in part to the national attention garnered by the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.[62] On February 17, 1937 the New York Times published a front-page story with the Committee’s findings. The article quoted President Roosevelt’s call for prompt action to aid the tenant class and “correct the ‘evils from which this large section suffers,’” calling for “a long-range Federal-State program to assist tenants in their climb toward ownership.” According to the Times, however, not all members of the Committee approved of this plan. Notably, W.L. Blackstone, the STFU’s representative on the Committee, recalled the Union’s “‘inability in the days of the AAA to get adequate redress of our grievances’” due to the USDA’s “domination by the rich and large land-owning class of farmers and their political pressure lobbies.’” Blackstone continued, “‘Ample evidence of these violations was in the hands of the AAA. Very little was done about it.’”[63] Even with representation, the STFU appealed to the press to further their programs of tenant rights and responsible government reaction on their behalf.

Governmental efforts to aid sharecroppers and tenant farmers began in 1935 with the creation of the Resettlement Administration (RA), which sought to relocate people displaced by the upheaval of the Great Depression, and the Farm Security Administration (FSA) of 1937, which offered government loans for tenant farmers to buy land and establish their own farms. In Arkansas, the RA set up a number of planned farm communities for displaced tenants, including the Dyess Colony, Lakeview, and Lake Dick Farm.[64] For historian Jeannie Whayne, the RA and the FSA, while noble in theory, still discriminated against STFU members, amounting to “government-run plantations.”[65] These programs unfortunately fell into the same trap as the aforementioned AAA tenancy protections: while an egalitarian solution to tenant displacement in theory, at the local level they were subject to planter control and anti-Union prejudice. STFU members more often sought refuge at the Delta Cooperative Farm at Hillhouse, Mississippi, a collective farm organized by the STFU in partnership with Sherwood Eddy, William Amberson, and other prominent socialists of the time.[66] While the RA (1935) and the FSA (1937) may not have been perfect solutions to the tenant crisis in the South, they showed true government interest and awareness of the problems of southern rural tenancy and poverty, thanks in a large measure to the publicity created by Norman Thomas and the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.

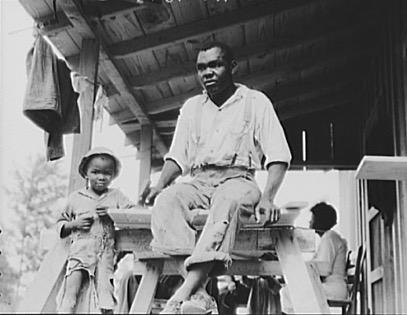

Evicted Arkansas sharecropper, building his new home at the STFU Delta Cooperative Farm in Mississippi. Dorothea Lange, July 1936.[67]

Conclusion

The STFU used the power of the press to bring awareness, incite outrage, and eventually inspire government action to alleviate the injustices suffered by Black and white sharecroppers and tenant farmers in Arkansas and beyond. In the key years 1934-1936, beginning with Norman Thomas’s exposé about the horrors of southern tenant farming, to the media frenzy surrounding the Ward Rodgers incident in Marked Tree, and culminating with Willie Sue Blagden’s flogging in the summer of 1936, the United States learned about “True Arkansas Hospitality,” the plight of southern sharecroppers, and planter violence. Due in large part to the STFU publicity machine, the Roosevelt Administration could no longer afford to cast aside the complaints of tenant farmers for the success of the now-defunct AAA.

The story of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union does not end with the March of Time newsreel in August of 1936. Reaching a peak membership of approximately 35,000 members in 1937, the union continued organizing, agitating, and striking.[68] In March of 1937, New York City hosted the first “Sharecroppers Week,” with speeches from union members Myrtle Lawrence, Henrietta McGhee, and songs from union troubadour John Handcox.[69] Photographers Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Ben Shahn photographed the sharecroppers and the STFU for the FSA to document life in the South. Louise Boyle went to Arkansas to photograph Myrtle Lawrence and other union organizers. Margaret Bourke-White and author Erskine Caldwell documented tenant life in their sarcastically biting photo book You Have Seen Their Faces.[70] In the late 1930s, several famous authors and photographers shared the plight of tenant farmers and sharecroppers, as well as astounding images of rural poverty, with the rest of the nation.

In September of 1937, the STFU joined the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), a subsidiary of the national Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). However, STFU leadership, especially H.L. Mitchell, bristled under the elite capture and communistic-leanings of the CIO and engineered a split from UCAPAWA in 1939.[71] In January of 1939, while the STFU was still affiliated with the CIO, a number of evicted Missouri sharecroppers set up a protest encampment along a well-traveled highway under the leadership of Black union organizer Owen Whitfield, which garnered a large amount of attention in the national press and from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.[72] However, the STFU never fully recovered from its ill-fated union with UCAPAWA and the CIO. Despite its many public relations successes, national recognition, and even a meeting between H.L. Mitchell and Eleanor Roosevelt in 1939,[73] the STFU soon found itself overcome by history and progress.

In the end, the STFU fell victim to factors beyond its control: mechanization and rapid industrialization due to World War II. Historian James Ross wrote: “These men who were present at the first meeting [in 1934] would not have believed that the union would only live a few years, and that all their dreams would be destroyed by the mechanization of farming and the enclosure movement which made sharecroppers and tenant farmers obsolete.”[74] Unforeseen in 1934, the STFU was fighting for a dying cause. Pete Daniel wrote that the STFU and sharecropping as a whole died at the hands of “the AAA, science, and war.”[75] Increasing cotton mechanization, largely funded by AAA parity payments in 1933, reduced labor requirements, forced tenant displacement, and the massive war-related industrial expansion of the early 1940s spelled the end of sharecropping and tenant farming and the rise of large, machine-intensive industrial agriculture.

In an historical accounting of the STFU, it is clear that, as a labor union, it left much to be desired. With limited power and money, it struggled to alleviate the practical suffering of the sharecroppers and tenant farmers it fought so hard to protect. In many cases, it actually increased this suffering when vengeful planters evicted, beat, and murdered union members. The STFU only saw one significant labor-related victory, when the cotton pickers’ strike of 1935 resulted in a wage increase for farm laborers. It fought to reform an abusive system that met a quick death with US entry into World War II in 1941. However, and most significantly, the words and actions of the STFU brought national awareness, outrage, and action on behalf of the poor southern farmers that it represented. From its founding in 1934 to the national cry for justice following the Willie Sue Blagden affair in the summer of 1936, the STFU and its allies fought a noble battle to remedy the injustices, abuse, and inequalities of southern sharecropping.

Bibliography

Secondary Sources

Auerbach, Jerold S. “Southern Tenant Farmers: Socialist Critics of the New Deal.” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1968): 113–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/40018503.

Cantor, Louis. A Prologue to the Protest Movement: The Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration of 1939. Durham: Duke University Press, 1969.

Conrad, David Eugene. The Forgotten Farmers: The Story of Sharecroppers in the New Deal. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1965.

Daniel, Pete. Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures Since 1880. Urbana: University of Illinois, 1985.

Grubbs, Donald. Cry from the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000. Original 1971.

Honey, Michael K. Sharecropper’s Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Manthorne, Jason. “The View from the Cotton: Reconsidering the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.” Agricultural History 84, no. 1 (2010): 20–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40607621.

Ross, James D., Jr. The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Arkansas. Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2018.

Whayne, Jeannie M. A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth- Century Arkansas. Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1996.

Woodruff, Nan Elizabeth. American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2003.

Primary Sources

Blagden, Willie Sue. “Arkansas Flogging.” The New Republic. July 1, 1936. https://web-p-ebscohostcom.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=07d4343f-716e-4346-89b2-7d0126ff5f29%40redis

“Bootleg Slavery.” TIME Magazine 25, no. 9 (March 4, 1935): 13–14. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=54805530.

Eds. Foner, Philip S. and Ronald L. Lewis. The Black Worker, Volume 7: The Black Worker from the Founding of the CIO to the AFL-CIO Merger, 1936-1955. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1983. https://temple.manifoldapp.org/read/the-black-worker-from-the-founding-of-the-cio-to-the-afl-merger-1936-1955-volume-vii/section/0fe40049-b544-43b3-aa3e-5ced1d2daba1

Herling, John. “Field Notes from Arkansas.” The Nation. Vol. 140, No. 3640. April 10, 1935. https://web-s-ebscohost-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=18&sid=09836beb-3841-40a2-8296-3234a57adf61%40redis (April 19 2023) .

Kester, Howard. Revolt Among the Sharecroppers. NY: Arno Press, 1969. Originally published in 1936.

March of Time, Volume 2, Episode 8, “King Cotton’s Slaves,” narrated by Westbrook Van Voorhis (7 August 1936; Time, Inc.), streaming at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-I5aX7qZtQ. Accessed 8 April 2023.

“Misery in Arkansas,” The Nation 140, no. 3636 (March 13, 1935): 294. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=13493707.

Mitchell, H.L. Mean Things Happening in This Land: The Life and Times of H.L. Mitchell, Co- Founder of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Montclair, NJ: Allanheld, Osmun, and Co., 1979.

Mitchell, H. L. and Howard Kester. “Share-Cropper Misery and Hope,” The Nation 142, no. 3684 (February 12, 1936): 184.

https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=13568614.

The New York Times

Rodgers, Ward H. “Sharecroppers Drop the Color Line.” The Crisis. Volume 42, Issue 6. June, 1935. Pages 168 and 178. https://archive.org/details/sim_crisis_1935-06_42_6/page/168/mode/2up?q=sharecropper

Thomas, Norman. The Plight of the Share-cropper: Including the Report of Survey of the Memphis Chapter L.I.D. and the Tyronza Socialist Party under the direction of William R. Amberson. New York: The League for Industrial Democracy, 1934. https://archive.org/details/ThePlightOfTheShare-cropper/mode/1up

“True Arkansas Hospitality,” Time, June 29, 1936. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,770194,00.html

Photographs:

Boyle, Louise (American photographer, 1910-2005). Black Workers Pick Cotton. 1937. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. https://jstor.org/stable/community.504173.

Boyle, Louise (American photographer, 1910-2005). Cotton Shack Surrounded by Ripe Cotton Plants. 1937. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. https://jstor.org/stable/community.503920.

Boyle, Louise (American photographer, 1910-2005). E.B. McKinney, STFU Vice President (Left), Standing with Two Unidentified Men, One of Whom Holds a Gun. 1937. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. https://jstor.org/stable/community.503932.

Boyle, Louise (American photographer, 1910-2005). Men, Women and Children, Including Ben, Myrtle and Icy Jewel Lawrence, Listening to Speakers at an Outdoor STFU Meeting. 1937. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. https://jstor.org/stable/community.504002.

Boyle, Louise (American photographer, 1910-2005). Myrtle Lawrence and Others Listen to a Speaker at an Outdoor STFU Meeting. 1937. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University. https://jstor.org/stable/community.504066.

Lange, Dorothea. “Evicted Arkansas sharecropper. One of the more active of the union members (Southern Tenant Farmers Union). Now building his new home at Hill House, Mississippi.” July 1936. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, fsa/owi Collection, LC-USF34-009549-C. http://archive.oah.org/special-issues/teaching/2006_12/sources/ex5_img009549.html 20 April 2023.

-

Michael Honey, Sharecropper’s Troubadour: John L Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), x. ↑

-

See David Eugene Conrad, The Forgotten Farmers: The Story of Sharecroppers in the New Deal (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1965), 84-5. ↑

-

I will refer to sharecroppers and tenant farmers interchangeably, although it is important to note that there were different levels of tenant farming. ↑

-

David Eugene Conrad, The Forgotten Farmers: The Story of Sharecroppers in the New Deal (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1965). ↑

-

Conrad, The Forgotten Farmers and Donald H. Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton: The Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and the New Deal (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, 1971). This idealism is possibly linked to the ongoing Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. ↑

-

Nan Elizabeth Woodruff, American Congo: The African American Freedom Struggle in the Delta (Cambridge: Harvard, 2003) and Jeannie Whayne, A New Plantation South: Land, Labor, and Federal Favor in Twentieth-Century Arkansas (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1996). ↑

-

Jason Manthorne, “The View from the Cotton: Reconsidering the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union.”Agricultural History 84, no. 1 (2010): 20–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40607621 and James D. Ross, The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union in Arkansas (Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 2018). ↑

-

Woodruff, American Congo, 152. ↑

-

From the song “Raggedy, Raggedy Are We” by John Handcox (1937), in Honey, Sharecropper’s Troubadour, 31. ↑

-

Conrad, Forgotten Farmers, 43. ↑

-

Louise Boyle, Cotton Shack Surrounded by Ripe Cotton Plants, 1937 (Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University). https://jstor.org/stable/community.503920. ↑

-

Conrad, Forgotten Farmers, 84-5. ↑

-

H.L. Mitchell, Mean Things Happening in This Land: The Life and Times of H.L. Mitchell, Co-Founder of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, (Montclair, NJ: Allanheld, Osmun, and Co., 1979), 40. ↑

-

Howard Kester, Revolt Among the Sharecroppers (NY: Arno, 1969), 57. Some of the white members at the first meeting had been members of the KKK in the past. In his memoir Mean Things Happening in This Land, Union co-founder H.L. Mitchell specifically identified one Burt Williams as someone with Klan ties that put his past aside for interracial cooperation within the union. See Mitchell, Mean Things, 47-8. ↑

-

Whayne, New Plantation South, 73-4. This numbers differed nationally. According to David Conrad’s Forgotten Farmers, 77% of Black farmers were sharecroppers nationally, compared to 46% of white farmers. Conrad, Forgotten Farmers, 2. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 56 and Mitchell, Mean Things, 48. For details of the Elaine Massacre of 1919, see Woodruff, American Congo, 82-94. . ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 56. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 56. It is important to note that Kester was not present at this meeting, and that Revolt Among the Sharecroppers is largely a work of STFU propaganda intended to elicit national sympathy and support. However, Kester joined the union shortly after its founding and was very close with most of the men who were at the original meeting, including Rev. A.B. Brookins, H.L. Mitchell, Clay East, and likely Isaac Shaw himself, who was close to Mitchell. Thus, Kester’s words may not be direct quotes, but they are supported by Mitchell’s autobiography (Mitchell was one of the present white men) and demonstrate the union’s use of popular media to gain national awareness and sympathy. ↑

-

Norman Thomas, The Plight of the Share-cropper (NY: The League for Industrial Democracy, 1934), 3. https://archive.org/details/ThePlightOfTheShare-cropper/mode/2up. Pellagra is a serious disease caused by malnutrition. This copy is a second printing, so it had been printed at least twice in 1934 alone. ↑

-

Thomas, Plight of the Share-cropper, 4. ↑

-

Thomas, Plight of the Share-cropper, 5. Peonage refers to a system of slavery that holds people in labor bondage until they pay off either financial or legal debts. ↑

-

John Handcox, “There Is Mean Things Happening in This Land” (1937). Song quoted in Honey, Sharecropper’s Troubadour, 71. A recording of John Handcox singing “Mean Things Happening in This Land” is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y6uBTphdCXw ↑

-

“Bootleg Slavery,” TIME Magazine 25, no. 9 (March 4, 1935): 13–14. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,931505-3,00.html ↑

-

Several sources, both primary and secondary, discuss the Rodgers incident. See Mitchell, Mean Things, 60-1 and Kester, Revolt, 67-8. ↑

-

Louise Boyle, Men, Women and Children, Including Ben, Myrtle and Icy Jewel Lawrence, Listening to Speakers at an Outdoor STFU Meeting, 1937 (Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University). https://jstor.org/stable/community.504002. ↑

-

Louise Boyle, E.B. McKinney, STFU Vice President (Left), Standing with Two Unidentified Men, One of Whom Holds a Gun, 1937 (Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University). https://jstor.org/stable/community.503932. ↑

-

The Associated Press, “FERA Teacher Convicted of Anarchy in Arkansas.” New York Times (1923-), Jan 22, 1935. https://search-proquest-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/fera-teacher-convicted-anarchy-arkansas/docview/101587156/se-2. ↑

-

Nation 140, no. 3631 (February 6, 1935): 143–46. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pwh&AN=13514079. ↑

-

Mitchell, Mean Things, 62. ↑

-

F. Raymond Daniell, “AAA Piles Misery on Share Croppers,” New York Times, April 15, 1935, p.6. ↑

-

F. Raymond Daniell, “Arkansas Violence Laid to Landlords, “New York Times, April 16, 1935, p.18. I have altered a racially offensive word in the text, although the Times printed the epithet in full. Union organizer Howard Kester characterized planter lackey Sage as someone who “serves his masters rather than the Master.” Kester, Revolt, 75. ↑

-

F. Raymond Daniell, “Farm Tenant Union Hurt by Outsiders,” New York Times, April 19, 1935, p. 18. ↑

-

Ward H. Rodgers, “Sharecroppers Drop Color Line,” The Crisis (Volume 42, Issue 6), June 1935: 168-169. ↑

-

Rodgers, “Sharecroppers Drop Color Line,” 178. ↑

-

Quoted in Kester, Revolt, 70. As far as I am aware, no recording of this speech has been made available online, although there are many mentions in the New York Times of Norman Thomas speaking over the radio. Kester does not provide a specific date. The Birdsong incident occurred on March 15, 1935. For more information on Birdsong, see Conrad, Forgotten Farmers, 166. ↑

-

John Handcox, “Roll the Union On” (1937), in Mitchell, Mean Things, 348. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 85. ↑

-

Mitchell, Mean Things, 81. Their goal was $1 per 100 pounds. ↑

-

For information on the September 1935 strike, see Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton, 85-6 ↑

-

STFU handbill, https://uca.edu/archives/files/2021/02/PAM-3566-p6-0002.png ↑

-

Louise Boyle, Black Workers Pick Cotton, 1937 (Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Martin P. Catherwood Library, Cornell University). https://jstor.org/stable/community.504173. ↑

-

See Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton, 88-91. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 26. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 26. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 27. ↑

-

Kester, Revolt, 51-2. ↑

-

See Louis Cantor, A Prologue to the Protest Movement: The Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration of 1939 (Durham: Duke University, 1969) and Nan Woodruff, American Congo, 188-9.. ↑

-

John Handcox, “Strike in Arkansas” (1936), in Philip S. Foner and Ronald L. Lewis, The Black Worker, Volume 7: The Black Worker from the Founding of the CIO to the AFL-CIO Merger, 1936-1955 (Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1983), 21 . https://temple.manifoldapp.org/read/the-black-worker-from-the-founding-of-the-cio-to-the-afl-merger-1936-1955-volume-vii/section/0fe40049-b544-43b3-aa3e-5ced1d2daba1 ↑

-

For accounts of the May 1936 strike, see Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton, 102 and Ross, Rise and Fall, 119. ↑

-

For details of the Earle attacks, see Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton, 110-113; Woodruff, American Congo, 171; and Mitchell, Mean Things, 87-9. Weems escaped his attackers and secretly fled to Illinois. ↑

-

Willie Sue Blagden, “Arkansas Flogging,” The New Republic, July 1, 1936, p. 236. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=07d4343f-716e-4346-89b2-7d0126ff5f29%40redis ↑

-

Mitchell, Mean Things, 88. ↑

-

“WOMAN FLOGGED IN COTTON STRIKE: MINISTER IS ALSO BEATEN AS HE ACCOMPANIES HER INTO AREA OF EASTERN ARKANSAS. ANOTHER MAN ATTACKED THOMAS PROTESTS TO ROOSEVELT, RECEIVES PROMISE OF INQUIRY BY ATTORNEY GENERAL,” New York Times, Jun 17, 1936, p. 3. https://search-proquest-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/woman-flogged-cotton-strike/docview/101859820/se-2. ↑

-

“Farmers: True Arkansas Hospitality,” Time, June 29, 1936. No. 26. P.12-13. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,770194,00.html ↑

-

“Farmers: True Arkansas Hospitality,” Time, June 29, 1936. No. 26. P.12-13. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,770194,00.html ↑

-

March of Time, Volume 2, Episode 8, “King Cotton’s Slaves,” narrated by Westbrook Van Voorhis (7 August 1936; Time, Inc.), streaming at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-I5aX7qZtQ. Accessed 8 April 2023. A partial transcript of the film is reprinted in Mitchell, Mean Things, 102-3. Mitchell is the source that this newsreel was shown in 6,000 theaters nationwide. He refers to the newsreel as “The Land of Cotton.” Different sources have different titles for the newsreel. ↑

-

For information on the Peacher Peonage case, see Grubbs, Cry From the Cotton, 118-119 and Woodruff, American Congo, 173-4. The Peacher case garnered even more national attention. ↑

-

Mitchell, Mean Things, 89. ↑

-

Jerold Auerbach, “Southern Tenant Farmers: Socialist Critics of the New Deal,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 27, no. 2 (1968): 113–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/40018503, 130. ↑

-

John Handcox, “No more Mourning,” in Honey, Sharecroppers Troubadour, 12. ↑

-

For more on the nullification of the AAA of 1933, see Conrad, Forgotten Farmers, 203. ↑

-

Pete Daniel, Breaking the Land: The Transformation of Cotton, Tobacco, and Rice Cultures Since 1880 (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1985), 98 and 182. ↑

-

Felix Belair, Jr., “PRESIDENT OFFERS PLAN TO CUT ‘EVILS’ OF FARM TENANCY: MESSAGE WITH REPORT OF HIS COMMITTEE SAYS MANY AMERICANS ARE ON ‘TREADMILL’ FAVORS A MODEST START KEY OF PROGRAM IS AID TO OWNERSHIP IN FURTHERANCE OF FADING NATIONAL ‘DREAM’ WIDE COOPERATION SOUGHT PRESIDENT URGES FARMS TENANT AID.” New York Times (1923-), Feb 17, 1937. https://search-proquest-com.aurarialibrary.idm.oclc.org/historical-newspapers/president-offers-plan-cut-evils-farm-tenancy/docview/101988606/se-2. ↑

-

“Farm Resettlement Projects,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/farm-resettlement-projects-5210/#:~:text=The%20two%20resettlement%20farms%20for,at%20a%20cost%20of%20%24163%2C679.79. The Cash family resettled at the Dyess Colony in 1935 with their young son, Johnny, who grew up there before moving to Nashville to pursue country music. https://dyesscash.astate.edu/about/ . Accessed 12 May 2023. ↑

-

Whayne, A New Plantation South, 213. ↑

-

John Handcox lived at Hillhouse for a period of time in 1936. The collective began in March of 1936 to house displaced tenants from the C.H. Dibble Plantation, evicted for their membership in the STFU, on land purchased by Sherwood Eddy of the YMCA and the National Christian Socialists. “Cooperative Farming in Mississippi,” Mississippi History Now, https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/cooperative-farming-in-mississippi, accessed 12 May 2023. ↑

-

“Evicted Arkansas sharecropper. One of the more active of the union members (Southern Tenant Farmers Union). Now building his new home at Hill House, Mississippi.” July 1936. Photo by Dorothea Lange.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, fsa/owi Collection, LC-USF34-009549-C. http://archive.oah.org/special-issues/teaching/2006_12/sources/ex5_img009549.html 20 April 2023. ↑

-

Woodruff, American Congo, 189. ↑

-

Mitchell, Mean Things, 139. ↑

-

Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces (Athens: University of Georgia, 1995). Originally published in 1937. FSA photographs are available at the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/collections/fsa-owi-black-and-white-negatives/about-this-collection/. Boyle’s photos are available at https://www.jstor.org/site/cornelluniversitylibrary/southern-tenant-farmers-union-photographs/?searchkey=1683927927559. ↑

-

For Mitchell’s account of the so-called “CIO Debacle,” see Mitchell, Mean Things, 166-182. ↑

-

See Louis Cantor, A Prologue to the Protest Movement: The Missouri Sharecropper Roadside Demonstration of 1939 (Durham: Duke University, 1969) and Mitchell, Mean Things, 171-181. ↑

-

Michell, Mean Things, 173. ↑

-

Ross, The Rise and Fall of the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union in Arkansas, 73. ↑

-

Daniel, Breaking the Land, 240 ↑